Left Wing History (4):

Waterloo 1815

Lack of Order

by Gary Cousins, Germany

| |

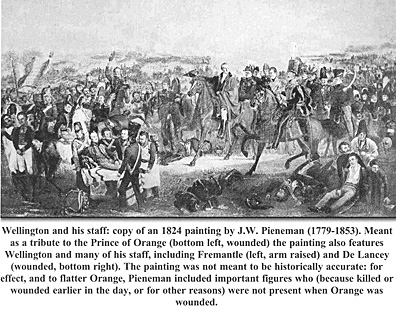

Wellington and his staff: copy of an 1824 painting by J.W. Pieneman (1779-1853). Meant as a tribute to the Prince of Orange (bottom left, wounded) the painting also features Wellington and many of his staff, including Fremantle (left, arm raised) and De Lancey (wounded, bottom right). The painting was not meant to be historically accurate: for effect, and to flatter Orange, Pieneman included important figures who (because killed or wounded earlier in the day, or for other reasons) were not present when Orange was wounded. If Vivian was telling the truth, still his account only gave his own narrow perspective, and the accounts of others suggest that more was going on than it disclosed. One possible reconciliation begins with Wellington’s intention to bring Vivian’s brigade in from the left as soon as possible, which would have been communicated and reiterated to all who needed to know. Perhaps, having received Wellington’s early order (through De Lancey), and Uxbridge’s instructions to all brigade commanders a little later, Vivian obeyed Wellington: he did not engage with his brigade during D’Erlon’s attack, and all afternoon limited his actions to keeping a lookout for the Prussians. But the staff officers visiting the left wing to check upon the progress of the Prussians, no doubt passing on news of events further to the right, were a constant reminder to Vivian of his earlier instructions. No fresh order could be given until Zieten’s Prussians were finally seen approaching; and when this happened, Vivian decided to move his brigade away from the left, but failed to persuade his senior officer Vandeleur to do likewise. In fact, if neither Vivian nor Vandeleur received fresh orders later in the day, both could arguably justify their conduct with reference to orders received earlier in the day. Vivian had hitherto obeyed his earlier order from Wellington, which implied that, as soon as the Prussians were sighted, his brigade would be released for action elsewhere; and when the Prussians were at last seen approaching, and knowing that cavalry was needed in the centre, Vivian used his initiative – perhaps in the spirit of Uxbridge’s order – and moved. As for Vandeleur, he was justified in resisting Vivian’s proposal to move both brigades to the centre: he had not received an early order from Wellington, and judged that Uxbridge’s instructions had not given him scope to leave the left wing with his brigade unless told, even though he was surely also aware of the shortage of cavalry in the centre and of the Prussian approach (indeed he may also have taken into account that Zieten had not yet joined the left wing). Instead Vandeleur waited until Uxbridge came out to the left, on his way to deliver formal orders to both him and Vivian. As Uxbridge, informed of the Prussian approach, made his way to the left, he met Vivian, leading his brigade towards the centre. Uxbridge congratulated him, and issued a formal order to Vandeleur to follow. No-one could have foreseen that Vivian’s movement would be followed by the hold-up of the advance guard of Zieten’s Prussian I Corps on the Ohain road, and the late French attack against the far left: but damage was limited when Zieten’s troops eventually joined and fought on the left wing, and Vivian’s Brigade gave much-needed support for the centre and made important charges towards the end of the battle. Given these results and the outcome of

the battle, perhaps Wellington was forgiving

in 1815, for no action was taken against Vivian.

Certainly Siborne believed his old chief

Vivian, [49] or if he did not, he was prepared to

indulge this “soldier’s tale”, for the version in

History largely repeated Vivian’s account. But

many distinguished old comrades of Vivian

claiming roles in this episode subscribed to or

read History when it was published in 1844

(two years after Vivian’s death): their silence

acknowledged either that its account was

largely truthful, or that they too were very

indulgent, because there is no record in

Siborne’s papers that any of them were indignant

and objected to History’s version (the

only dissent came from Müffling, as explained

earlier).

If Vivian’s account and History were not

truthful, exactly what happened to bring

Vivian’s and Vandeleur’s Brigades in from

the left wing requires another explanation, and

is still not exactly clear from the accounts of

others who claimed involvement.

Whether or not one believes Vivian’s

claim, it is suggested that Siborne’s version in

History was an incorrect and incomplete summary

of events on the left wing on the 18th

June. The claims of others, and the broader

picture and the detail of what really happened

which they might give, were largely ignored.

There is no overview of Wellington’s intentions

for the cavalry on the left wing, nor any

detail of how he carried through those intentions

during the day, probably through Uxbridge

and perhaps involving Müffling, and

by the constant use of staff officers. History

compounded the early order to Vivian from

Wellington (through De Lancey) – not otherwise

mentioned in History – with the errands

of staff officers throughout the afternoon –

details of which were largely omitted, and

Delancey Barclay’s specific errand was forgotten

– into the statement that Vivian had

“understood from Sir William Delancey and

other staff officers” that there was a shortage

of cavalry in the centre, thus leaving the false

impression that De Lancey personally told

Vivian of this situation in the early evening.

Uxbridge’s early instructions to his brigade

commanders are only briefly mentioned elsewhere

in History; [50] and his belated order to

Vandeleur, and the order which Seymour delivered

to Vivian when he arrived in the centre

(omitting Seymour’s name to spare his feelings),

are the only orders in the early evening

mentioned in History; and what his staff said

was ignored. Müffling’s claims are also given

no place, for reasons stated earlier.

It is a pity that Siborne appears not to

have investigated this matter further with

those who claimed involvement and who were

still alive. It is true that some accounts were

not available to Siborne (for example Lady de

Lancey’s Narrative of 1816 was not published

until almost a century later); and De Lancey

died in 1815 and Delancey Barclay in 1826.

But many of those involved were Siborne’s

correspondents: for example, all of Seymour’s

letters, including the one in which he claimed

to have delivered an order to Vivian, were

written in 1842, five years after the original

letter of 1837 from Vivian. Vivian could have

been quizzed up until his death in 1842, and

all of the others before the 1st edition of History

was published in 1844; indeed most lived

to see History run to a 3rd edition in 1848, and

outlived Siborne (died 1849).

But there is no such correspondence in Siborne’s papers.

However, whether intentionally or otherwise,

Siborne’s History may have got one

aspect right, for although Wellington is not

mentioned in Vivian’s account, at the end of Siborne’s version Vivian is praised for his

action by Uxbridge, who was not “much

pleased at what I had done”, as in Vivian’s

account, but “…much pleased to find that the

Duke’s wishes had thus been anticipated...”.

It was what Wellington had wanted all

along.

Left Wing History (4) Vivian’s 6th (Light) Cavalry Brigade on the 18th June 1815

Left Wing History (3) Vivian’s 6th (Light) Cavalry Brigade on the 18th June 1815

Left Wing History (2) Prussian I Corps

Left Wing History (1) Waterloo 1815: Vivian's 6th Cavalry Brigade

|

It may be “a matter of perfect indifference

to history”, but did Vivian act without orders?

It may be “a matter of perfect indifference

to history”, but did Vivian act without orders?