Very recently, there has been an attempt from some quarters to author revisionist history on the Prussian army of 1806. The bill of goods being sold by the revisionist school is that the Prussian army on the fields of Saalfeld-Jena-Auerst was no longer the same kind of army that fought in the Seven Years War. Limiting arguments to regulations and inspection decrees which focuses on the increase in the number of tirailleurs to be pulled from each battalion, revisionists draw the conclusion that the Prussian army of 1806 was no longer a Frederician "museum piece", but a Napoleonic army which just happened to be a little rusty. What the revisionists completely fail to examine is the most crucial element of any assessment of an army under fire - how the army was organized, how well it was led and what actually happened on the battlefield. This researcher argues that close investigation of the combats of 1806 will put to rest any notion of the revisionist myth.

The Prussian army of 1806 operated on a modified regulation that was almost 100 years old. Given by Frederick William in 1714, the regulation went under rewriting in 1726, 1742, 1743, and finally republished with minor alterations in 1766 and 1773. Although the Prussian battalion had 5 companies, these served only in an administrative capacity. In battle during 1806, the battalion operated in 8 tactical platoons with a field strength of over 700 combatants. Two battalions plus a division (2 companies) of grenadiers comprised a regiment. However, the grenadiers were detached to form converged grenadier battalions along with other regiment's grenadiers and thus never served along side the rest of the regiment.

Tactics were relatively straightforward. The Prussian infantry were deployed in line of three ranks and trained to attack and overwhelm their opponents with sustained, rapid firepower. When the opponent was visibly shaken by this firepower, and when time was right, the infantry was attack with cold steel. To state that the Prussians were "trained" to attack might be an understatement. Their officer corps was totally and completely indoctrinated in the spirit of the offensive. For Frederick the Great, the highest expression of offensive tactics was the attack in echelon - or oblique attack - it's success being best evidenced in the impressive victory over the Austrians at the Battle of Leuthen.

Formed, disciplined Prussian battalions firing series of rapid volleys and, when appropriate, advancing was often cause for the opposition to give way from under the constant pressure. During the wars of Frederick, unformed Prussian troops, such as the numerically diminutive J corps and the ill disciplined frei-battalions, were always placed on the flanks or in the rear of the army - almost always far removed from the intended field of battle and the formed troops.

The Prussian artillery arm - considered by a dirty, inferior service where the bourgeoisie labored - held the least attraction for those in charge of the army. As a result, Prussian artillery performance was always lacking compared to the Austrian and French of the Seven Years War. This deficiency grew even more pronounced during 1806. The Prussian artillery had little-to-no coordination between batteries. As a result, it was very rare to find a concentration of two or more batteries. The Prussian field batteries numbered 8 pieces of ordnance (6 cannons and 2 howitzers) with the horse artillery often operating in half-batteries of 4 pieces. In 1806, every battalion of foot was supposed to be supported by 2 pieces of ordnance - 6 pdrs. for the musketeers and grenadiers battalions, and 3 pdrs. for the fusiliers battalions. However, it is clear from all the reports that the fusiliers did not take their 3 pdrs, into the field in 1806. While the battalion guns did augment the firepower of their parent formations, there is no evidence that would indicate coordination between the pieces of one regiment and those of another. As a result, the number of guns present in the Prussian army did not have a corresponding impact as would the same number of French pieces discussed later in this presentation.

Far different, however, from the artillery was the reputation of the Prussian cavalry. Brilliantly led and superbly mounted during the wars of Frederick the Great, the Prussian horse were fabled for their heroics on virtually every battlefield. From Hohenfriedberg to Rossbach to Zorndorf and beyond, Prussian cavalry and leaders often distinguished themselves against Russian, Austrian, French, and even Saxon cavalry. The fierce reputation of the Prussian cavalry clearly preceded them in the 1806 war with France. One cannot imagine a better testimonial to this reputation than the following quote made on October 5 - nine days before Auerstädt - by Marshal Davout, to the officers and men of his legendary 3rd Corps: "The Prussians are counting on their cavalry for victory. Practice well the drill of forming square; your squares will amputate the fame from this cavalry."

The 1806 Prussian army organization, overlooked by revisionists, was till along the lines of the armies of the ancien regime. While a division organization did exist on paper, it was little more than a reference to which brigades were attached. There was virtually no staff at the division level as virtually all orders came for army command. Although deployment and commitment to battle were attempted on a divisional scale, in reality it was only accomplished by brigade. Furthermore, the composition of the brigades changed almost continuously as regiments were shifted from one brigade to another, and brigades transferred from one division to another. The very nature of this mind set prevented any form of genuine coordination of troops or esprit de corps above the regimental level.

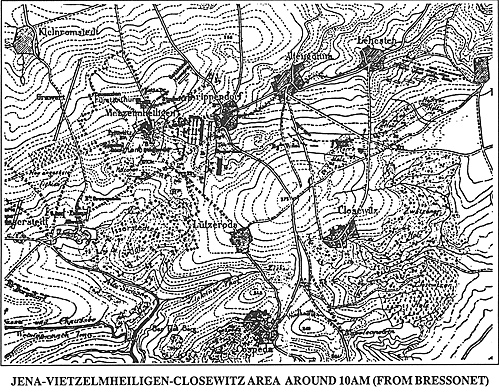

Overall, Prussian tactical deployment of troops were predictable. Forests and villages were areas which Frederick as well as the generals of 1806 tried to avoid fighting. Rather, forests and villages were places in which light troops could operate without interfering with the fields of fire and corresponding serious work to be performed by the formed troops. With respect to villages, Prussian doctrine rarely - if ever - called for defense of build-up areas. When necessary, they would storm enemy held villages and strong points which threatened their ordered lines of battles. However, when given the choice, Prussian arms did not opt fro placement in any villages because such deployment would affect their offensive, firepower minded tactics. This is plainly demonstrated by Prince Louis' deployment at Saalfeld as well as General Tauenzien's abandonment of the village of Vierzehnheiligen at Jena.

Finally the importance of the Prussian command mind set to wage aggressive offensive warfare in the echelon - or oblique - style and manner of Frederick the Great cannot be overemphasized. This obsession permeated down the chain of command to the lowest levels of tactical deployment and only served to compromise the splendid regiments which faced Napoleon's modern war machine.

Jena Area: 10am

War Against Prussia, 1806 Myths and Reality of Jena-Auerstadt

- I. Background and Purpose

II. The Prussian Army

III. The French Army

IV. Conclusions: Similarities and Differences

V. Jumbo Map: Jena (extremely slow: 454K)

VI. Jumbo Map: Saalfeld (extremely slow: 515K)

Related

War Against Prussia, 1806 Comparison of French and Prussian Tactics During the Campaign of 1806-1807 by Jean Lochet

- Introduction: Etude Tactique sue la Campagne de 1806

I. Bressonet's Conclusions on the Campaign of 1806

II. Battles Around Localities

III. Comments and Conclusions on Bessonet: Lochet and Griffith

IV. Overall Conclusions

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 2 No. 1

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com