Napoleon’s Eagles (Part 3)

Russia 1812

Interregnum and Retreat

by Kevin Birkett, FINS, Eire

| |

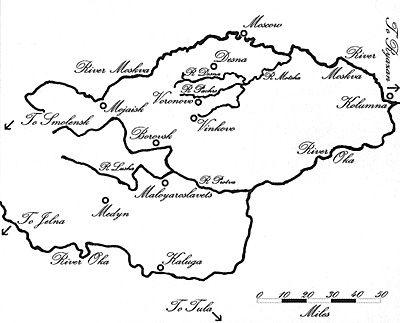

Entering the Kremlin and climbing the tower of Ivan the Great, Napoleon surveyed his prize. Gazing out across the crow infested rooftops he was greeted by a gloomy silence broken only by the steady tread of his infantry and the rumble of its accompanying artillery. Barely one sixth of the city’s population of 300,000 had remained to witness the fall of their capital. Victories had been gained but the enemy never defeated. This had been a campaign like no other that he had fought. Perhaps now that Moscow had been occupied the Tsar would sue for peace. Spreading out across the vast almost deserted city the glum thoughts that occupied Napoleon were far from the minds of the rank and file of his army. All around them luxurious mansions and overflowing warehouses bore silent witness to Moscow’s status as the bazaar of the east. Rugs from Persia, silks from China and furs from Siberia greeted the soldiers at every turn. Accustomed to occupying burnt out shells this was truly manna from heaven to the half starved semi-clothed soldiery. Soon the iron bonds of discipline began to breakdown as the rapacious men of Napoleon’s Grande Armée fanned out in search of plunder. The rank and file of the Grande Armée were not the only men spreading out across Moscow intent on nefarious activity. In the afternoon of the 15th one of the biggest warehouses in the city burst into flames. Rushing to the scene the men of the Imperial Guard tried to extinguish the flames but the absence of all fire fighting equipment thwarted their efforts. That night a gale sprang up from the east spreading the conflagration further. Throughout the city other smaller fires also sprung up. Rushing to these new fires the French infantry apprehended numerous individuals carrying inflammable material at the end of long poles. Questioned under threat of death these incendiaries soon revealed the truth, the fires had been set under the orders of Count Rostopchin, the former governor of the city. As day broke on the 16th the extent of the conflagration soon became apparent. Fanned by the increasingly violent wind the flames had already consumed much of the northwestern corner of the city. Unable to extinguish the fires the terrified soldiers of the Grande Armée were left with no option but to abandon the city to the flames. For three days and three nights the fires raged on until, having consumed five-sixths of the city and some 15,000 soles, on the 18th September the equinoctial rains fell extinguishing, at last, the terrible flames. Kutusov meanwhile had been putting his designs into operation. Since abandoning Moscow the Russians had been steadily retiring southeast along the Ryazan road shadowed by Sebastiani commanding the French advance guard. Having retired some 30 miles the Russians, stimulated by a fervent desire to revenge the burning of Moscow, which they believed to be the work of the French, abruptly turned to the southwest rather than continue as planned along the road to Kolumna. Completely deceiving their pursuers by the 19th the Russians were established behind the River Pachra from where Kutusov dispatched Cossacks to harass the French communications. News of the deprivations of the Cossacks and word from Sebastiani that he had lost the Russian army reached Napoleon on the 20th. Suspecting the true nature of the threat facing his army the Emperor reacted quickly. Murat was immediately sent, together with Poniatowski’s V Corps, to resume command of the advance guard with orders to reconnoitre along the Tula road. Meanwhile Bessières was given command of Grouchy’s III Cavalry Corps and two divisions of Davout’s I Corps with to sweep the old Kaluga road while Broussier’s division of the IV Corps did likewise along the new Kaluga road. Quickly discovering Sebastiani’s error, Murat was soon hot on the trail of his quarry. Bessières meantime had discovered Miloradovitch’s rear guard at Desna. His position revealed Kutusov was faced with a dilemma. Should he stand and fight or withdraw. Uncertain of the strength of his opponents, and expecting reinforcements from the south, the Russian generalissimo chose the latter and on the 27th retired along the Kaluga road in search of a more secure position. Passing through Voronovo, Vinkovo and Tarutino the Russians eventually established themselves along the steep banks of the River Nara. Following up Murat and Bessières, with insufficient numbers to mount a serious attack, halted before the Russian positions and awaited further instructions from Moscow. In Moscow Napoleon was also faced with a dilemma. He had hoped that the occupation of the city would have induced the Tsar to make peace but thus far no word had been received from St. Petersburg. Disappointed he began to formulate further plans to bring the campaign to a successful conclusion. A retrograde movement on Smolensk followed by a spring offensive against the northern capital was his preferred option, but unfortunately the morale of Grande Armée had plummeted to such an extent since the burning of Moscow that the army would require a period of repose before it could be asked to undertake such a task. Resigning himself to an inevitable delay before his plans could be put into effect Napoleon set about organising his forces for any eventually. Opposite the Russian camp at Tarutino Murat was ordered to remain in observation and to rest and feed his troops as best he could. In Smolensk Victor was ordered to make himself ready for a move in any direction. Junot received orders to provide transport for those wounded who, following a period of convalescence, would be fit to once again follow the eagles. In the event that it would become necessary to winter in Moscow the area around the Kremlin was levelled and the ancient fortress armed with 600 guns. While these and the numerous other orders necessary for the resumption of hostilities were fulfilled Napoleon decided, in the absence of any Russian peace delegation, to initiate some diplomatic moves of his own. Peace Overtures On the 4th October one of Napoleon’s most trusted aides-de-camp, General Lauriston, set out for Kutusov’s camp. Arriving later that day his first attempt to see the Russian commander met with failure causing him to return to Murat’s headquarters. However fearful that this rebuff to the emissary of the Emperor would bring a wrathful Grande Armée down on their heads, a situation that was not at all in accordance with Kutusov’s designs, the Russians reopened negotiations. Eventually admitted into the presence of the Russian generalissimo Lauriston made his case for a cessation of hostilities. The wily Kutusov listened to Lauriston’s arguments with interest but, having neither the authority nor his own military preparations completed, he refused to negotiate. Instead he proposed that one of the Tsar’s aides-de-camp be sent to St. Petersburg for further instructions. Unable to make any further progress, apart from an agreement that firing should cease alone the line of advanced posts, Lauriston returned to Moscow to report to his imperial master. Disappointed but not surprised by the turn of events Napoleon tentatively pencilled in the 20th October as the departure date for the Grande Armée. Meanwhile he continued his military preparations and awaited news from St. Petersburg. Whilst these things were transpiring in Moscow the Tsar was making preparations of his own. Since leaving the army on the banks of the Dvina in July the Tsar had resided in St. Petersburg devoting his days and nights in preparing resources and forming alliances with which to fight the invader. On the 18th July he had concluded an alliance, both defensive and offensive, with Great Britain. On the 28th August in Åbo, Finland he met with Bernadotte, recently elevated to the rank of Crown Prince of Sweden. Reassured of Sweden’s pacific intensions, and having extracted a Swedish promise of military aid, he ordered Steinheil’s Army of Finland into Livonia where it was to join Wittgenstein. On his return to St. Petersburg from Åbo the Tsar was once again drawn to Phull’s original plan of campaign. A plan that seemed inconceiva-ble on the banks of the Dvina now appeared feasible. With the Grande Armée 520 miles from the Niemen it would be possible for Tshitsagov, commanding his own and Tormassov’s armies, and Wittgenstein to operate on the flanks and rear of the French. Accordingly General Tchernichev was dispatched to Kutusov’s and Tshitsagov’s headquarters with details of the plan. Kutusov was to maintain his position while Tshitsagov, advancing from Volhynia, was to ascend the Dnieper and Berezina there to unite with Wittgenstein who, having forced the line of the Dvina, was to march south. So it was, on the morning of the 18th while reviewing Ney’s troops, that Napoleon heard the sound of heavy gunfire from the direction of Kaluga. Soon afterwards a messenger arrived relating how Murat had been surprised in his cantonments around Vinkovo but had, through his own bravery, extricated his troops. Suspecting that Murat’s escape owed more to luck than bravery, and fearing for his communications, Napoleon ordered his corps to concentrate, except for Junot’s VIII which was still in Mojaisk guarding the wounded from Borodino, ready to march on Kaluga the following morning. To compliment these orders he instructed the governor of Smolensk, Baraguey d’Hilliers, to march, with a division that had formed from demibrigades de marche, on Jelna, while Victor, who was also in Smolensk, was ordered to stand ready to assist him. The 19th dawned bright and clear. The men of Eugène’s IV Corps were the first to leave followed by Davout’s I, Ney’s III and the Imperial Guard while left behind in the Kremlin Mortier’s 10,000 men, consisting of the Young Guard and dismounted cavalry, prepared the fortress for demolition. Although the march had commenced at 2 a.m. by midday vast crowds were still pushing their way through the gateways of the half-ruined city and along the old Kaluga road. Encumbered by numerous carts piled high with food and booty from the pillaged city, giving the Grande Armée the appearance of the Mongol hordes of old, the 95,000 men and 500 guns that remained around the eagles made slow progress. Joining the army on the evening of the 20th between Desna and the Pachra Napoleon reviewed his options. He had originally intended to advance along the old Kaluga, punish Kutusov for the impudence he had shown in attacking Murat before, having occupied Kaluga, deciding whether to winter there or continue to withdraw westwards. Now information from Murat, in Voronovo, indicated that the Russians were still strongly posted in their camp at Tarutino. Fortunately there was another road available, on which Broussier was already positioned, which, passing through Borovsk and Maloyaroslavets, avoided this formidable position. The following morning the IV Corps followed by the I Corps and Imperial Guard set out for the new Kaluga road leaving the III Corps to cover the flank march. This new line of advance was not without its consequences as, following the departure of Ney and Murat, Moscow would be uncovered. Realising that Mortier’s position would soon be untenable Napoleon ordered the marshal to evacuate the Russian capital. In addition Junot was ordered leave Mojaisk and retire, with all the wounded that could travel, along the Smolensk road. By the 23rd Eugène had pushed through Borovsk and his advance guard, Delzons division, had pushed two battalions into Maloyaroslavets. The Russians meanwhile were blissfully unaware of the French flank march. However the position of Broussier’s division was known to them and had been causing them some concern. Determined to deal with this thorn in his side Kutusov ordered Doctorov’s Sixth Corps to descend on the isolated division. Reaching Aristovo on the evening of the 22nd Doctorov received intelligence that far more than a single division was marching on his right. Reporting his findings to Kutusov, he received instructions to march with all possible haste on Maloyaroslavets, the only position offering any possibility of halting the French advance. Arriving before Maloyaroslavets at 4 a.m. on the 24th October Doctorov ejected Delzons’ battalions from the town and across the River Lusha. Throughout the day the battle for the vital river crossing raged on. Eventually the Russians withdrew leaving the town in French hands. Napoleon now faced a predicament. The Russians had withdrawn a few miles and showed every intension of disputing any further advance along the Kaluga road. Calling a council of war Napoleon consulted his senior officers. An advance on Kaluga was still possible but a battle would have to be gained and the resultant casualties would be considerable. Nobody present showed much enthusiasm for this option. Davout proposed that the retreat should be undertaken via Medyn and Jelna on Smolensk but the majority favoured a withdrawal along the more secure Mosocw/Smolensk road. Considering these opinions overnight in the morning of the 26th October the Emperor made his fateful decision; the Grande Armée would march immediately on Mojaisk and the Moscow/Smolensk road. Ironically even as Napoleon was issuing these orders Kutusov was withdrawing towards Kaluga intent on finding a more defensible position. Napoleon's Eagles (Part 3) Invasion of Russia 1812

Battle of Borodino Interregnum and Retreat Battle of Vinkovo Jumbo Map of Battle of Borodino (extremely slow: 372K) Napoleon's Eagles (Part 2) Invasion of Russia 1812

Battle of Smolensk Sideshow: Oudinot's Dvina Campaign First Battle of Polotsk Volhynian Summer Jumbo Map of Battle of Smolensk (very slow: 278K) Napoleon's Eagles (Part 1) Invasion of Russia 1812

From the Niemen to the Dvina Battle of Saltanovka Maneuver of Vitebsk Battle of Ostronovo Maneuver of Smolensk Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire # 80 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 2004 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com |

15th September to 26th October 1812

15th September to 26th October 1812