Napoleon’s Eagles (Part 2)

Russia 1812

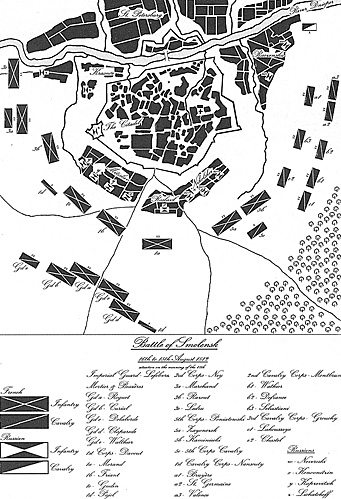

Battle of Smolensk

by Kevin Birkett, FINS, Eire

| |

Rapidly pressing forward the Württembergers of Generalmajor Ernst von Hügel’s brigade waded thigh deep through the dark waters of the Dnieper. Ascending the right bank they were quickly joined by a detachment of Portugeuese infantry and together they plunged into the blazing northern suburbs of the ancient city intent on dislodging its Russian defenders. Jumbo Map of Battle of Smolensk (very slow: 278K) Taking shelter behind a garden hedge Leutnant Christian von Martens of the Württemberg infantry regiment ‘Prinz Paul’ took a drink from a French officer’s water-bottle and could not help but wonder how fate had brought men from every corner of Europe to fight for the ruins of what was once Smolensk. Two days earlier, on the 16th August, Martens together with the rest of Ney’s III and Grouchy’s III Cavalry Corps had ascended the hills that surrounded the southern suburbs of Smolensk. Ney and Grouchy had been racing to enter the city before reinforcements could reach it, however as they cast their eyes beyond the Dnieper they could clearly see that the race had been lost. Below them they a dense column of Russian infantry, Raevski’s Seventh Corps, was entering the city. Hastening to occupy the city before the Russians could establish themselves Ney ordered elements of Ledru’s division to scale the walls but to no avail, the weight of musketry was such that the attack was beaten off with heavy losses. Unwilling to risk further casualties Ney called off the attack and awaited the arrival of the Emperor. On his arrival Napoleon conducted a thorough reconnaissance of the city’s perimeter with a view to renewing the assault the following morning. The city of Smolensk stands on the Dnieper encircled by low hills. On the left bank lay the old town surrounded by an ancient brick wall, 15 feet thick at the base and 25 feet high, which was flanked at intervals with large towers. The southwestern corner of the walls were protected by an earthen pentagonal citadel and the whole was surrounded by a ditch, covered way and glacis all constructed long before the time of Vauban. In front and around the city were a number of suburbs. To the west, in the angle form by the city walls and the river, stood the suburb of Krasnöe; to the south the suburbs of Mitislav, Roslavl and Nikolskoi; while to the east a final suburb, Raczenska, rested on the Dnieper. Meanwhile on the right bank stood the new town and suburb of St. Petersburg through which masses of Russians infantry were moving intent on defending the city and its ancient Byzantine cathedral. On hearing news of Napoleon’s outflanking manoeuvre the Russian commanders had called off any further pretence of taking the offensive and retraced their steps back to Smolensk. Raevski’s troops had been the first to arrive, after the much-abused division of Neveroski, and it was these that had thwarted Ney’s early attempt to storm the citadel. However, as the 16th wore on the troops of Barclay’s First Army of the West began to arrive in ever increasing numbers. Assuming responsibility for defending Smolensk, Barclay ordered Bagration withdraw Raevski’s troops and, together with the remainder of his army, take up a position on the Moscow road. Meanwhile Doctorov’s Sixth Corps, re-inforced by the divisions of Neveroski and Konovnitzin, was given the onerous, though honourable, task of defending the city. While Barclay was thus engaged with manning the defences of the city Napoleon was positioning his troops so as to bring about its downfall. On the left, facing the suburb of Krasnöe, he placed Ney’s three divisions; in the centre opposite the suburbs of Mitislav and Roslavl he placed Davout’s three divisions; opposite Nikolskoi and Raczenska Poniatowski’s Poles; and finally on the extreme right, Murat’s cavalry. By the morning of the 17th all was ready for the assault on the city and its 30,000 defenders. Yet Napoleon hesitated. To attack so well a defended position was not a task to be undertaken lightly and with luck, or so the Emperor reasoned, the Russians may take leave of their senses and cross the river to engage the French in open combat. By 10 a.m., it being obvious that Barclay was not about to commit that cardinal error, the signal to attack was given. Advancing on to the plateau on the right Bruyère’s cavalry drove off a Russian dragoon brigade thereby allowing a battery of 60 guns to be established, which playing on the bridge across the river, made communications between the two halves of the city hazardous in the extreme. To Bruyère’s left, Poniatowski penetrated into the suburbs of Nikolskoi and Raczenska despite the stout resistance of Neveroski. In the centre Davout drove in the Russian outposts and opened a destructive fire on the suburbs of Mitislav and Roslavl, which were defended by the divisions of Konovnitzin and Kapzevitsch. Meanwhile, to the left, Ney advanced Marchand’s Württembergers against the citadel. Profiting from his experiences of the previous day however Ney directed that the attack be made via the suburb of Krasnöe. This the Württembergers did, quickly overcoming the resistance of Lichatcheff’s division, which guarded that suburb. The entry of Ney’s troops into the Krasnöe suburb was the signal for Davout to launch a concerted attack on those to his front. Directing Morand to advance along the road that ran between Mitislav and Roslavl and onto the Malakofskia gate, Davout personally led Gudin’s troops against Kapzevitsch in suburb of Mitislav. Entering the suburb at the point of the bayonet they drove the Russians from street to street before finally penetrating to the walls of the city itself. Meanwhile Friant had carried the suburb of Roslavl and like the other two divisions arrived at the city walls. The Russians however were not yet ready the relinquish possession of the suburbs. Aided by at powerful reinforcement, Eugen of Württemberg’s division, they sallied forth from the gates of Nikolskoi and Malakofskia, Eugen from the former and both Eugen and Konovnitzin from the latter. Pushed home with great vigour these attacks required all of Davout’s and Poniatowski’s determination to repulse them. At length just the walls separated the combatants, the Russians unable to counter-attack and the French unable to penetrated the city; the 12 pounder artillery of the Grande Armée having little effect on the ancient walls. Unable to gain entry Napoleon resolved to bombard the city in the hope that the resultant fires would render the Russian position untenable. Davout meantime had discovered an ill-repaired breach from a previous conflict and had given orders for Friant to assault it the following morning. Notwithstanding the success of his defence thus far, Barclay had resolved to aban-don the old city to the French. So it was on the night of the 17th/18th that the Russian troops slipped stealthily from their positions and crossed the Dnieper, burning the bridge behind them. At 3 a.m. on the 18th August a patrol from the I Corps approached the walls. Finding that they were deserted the patrol penetrated into the city. News of their discovery quickly spread and soon the advance guards of the I, III and V Corps were fanning out through the fire-ravaged streets. At 9 a.m. the Württembergers and Portugeuese of the III Corps succeeded in establishing a bridgehead across the Dnieper but hemmed in by Korf’s rear guard they were unable to do more than cover Ney’s attempts the repair the bridge. As darkness fell the French were at last able to re-establish the river crossing. The III Corps quickly crossed the river and occupied the rest of the city virtually unopposed. Smolensk had fallen but at an appalling cost. Some 10,000 Frenchmen and their allies lay dead in the suburbs and the ditch that surrounded the city, while 12,000 Russian dead littered the suburbs, walls and the streets beyond.

|

16th to 18th August 1812

16th to 18th August 1812

The Battle of Lubino or Valutino-Gora

The Battle of Lubino or Valutino-Gora