Napoleon’s Eagles (Part 3)

Russia 1812

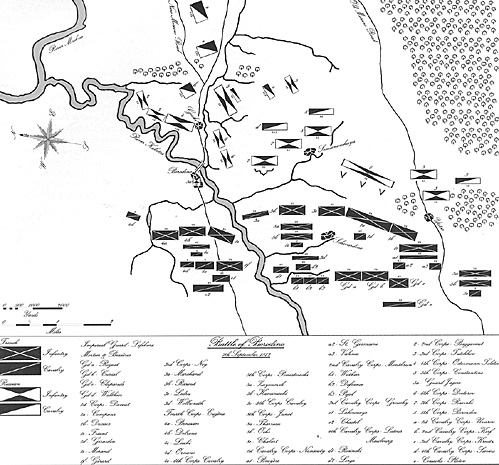

Battle of Borodino

by Kevin Birkett, FINS, Eire

| |

Drawing back the curtains of his tent the Emperor strode between the two sentries and moved to join a large group of officers. At that moment the sun broke through the early morning mist. ‘Behold the sun of Austerlitz!’ exclaimed the Emperor, remembering a similar morning nearly seven years earlier. With that he mounted his horse and set off at a gallop towards the right wing. An hour later the guns of the Grande Armée belched forth death and destruction. The long anticipated battle with the Russians had begun. The Grande Armée, which had been shadowing the Russians for some time, had finally run its quarry to ground near the little village of Borodino some seventy-five miles west of Moscow on the main Smolensk/Moscow road. Unfortunately for the French the ground was not of their choosing. Arriving on the 5th September Napoleon had spent much of the 6th personally surveying the area and had made a number of observations. The right of the Russian position, to the north of Borodino, was protected by the deep bed and steep escarpments of the Kalatsha, which meanders approximately west to east towards its confluence with the Moskva. In the centre the high road to Moscow, which crossed from the left to the right of the Kalatsha at Borodino before climbing the plateau of Gorki, had been made equally inaccessible by the addition of an earthwork. It was only to the right of Borodino, where the hills were less prominent and defended only by dry ravines of no great depth, that the ground became more practicable. The first little hill to the right of Borodino was covered at its base with brushwood and terminated in a tolerably wide plateau surmounted with a large redoubt, which the Russian commander Kutusov had caused to be constructed to protect his exposed left. This redoubt, whose embrasures contained twenty-one large guns, was destined to acquire the name of the great redoubt. To the right of this position stood another hill, which was separated from the first by the little ravine of Semionovskaya and the village of the same name. This hill, smaller but steeper than the first, was topped by three flèches, two facing the French line and a third a little to the rear facing the ravine. The village of Semionovskaya had been burnt to the ground by the Russians and its ruins surrounded by a mound. Further to the right lay the old post road running through heavily wooded countryside to the village of Utitsa. Given the strength of the positions downstream of Borodino, Napoleon resolved to make his principle effort to the right of the Kalatsha. While the Emperor had been making his observations Davout too had been engaged in reconnaissance. Penetrating into the woods on the French right he became convinced that an outflanking manoeuvre was possible. Outlining his plan to Napoleon, Davout pledged to have the whole of the I Corps in position to attack the left rear of the Russian line by 8 a.m. the following morning. Thus two plans presented themselves to the Emperor however, fearful of splitting his force in the face of a powerful enemy and afraid that should the Russians perceive the manoeuvre they would once again retire, he rejected Davout’s in favour of his own. Having come to his decision Napoleon communicated his plans and assignments to his corps commanders. On the extreme left of his line Eugène’s IV Corps was charged with masking those parts of the Kalatsha made inaccessible by the steepness of its banks, occupying Borodino and attacking, from both the flank and the front, the great redoubt. To aid him in his task he had been loaned Grouchy’s III Cavalry Corps and two divisions of the I Corps, Morand’s and Gérard’s, for the day. To Eugène’s right Ney with his own III Corps and Junot’s VIII, was to assail the flèches from the front while Davout, with the remaining three divisions of the I Corps, was to assault then from the flank by the skirts of the wood. Finally Poniatowski’s V Corps was to endeavour to turn the Russian position by penetrating the wood by the old Moscow road and debouching on Utitsa. To the rear of these formations was Murat’s cavalry: Nansouty’s I Cavalry Corps behind Davout; Montbrun’s II behind Ney, and Latour-Maubourg’s IV around Schivardino with the Imperial Guard. Although the Grande Armée had suffered a steady haemorrhage of manpower since the start of the campaign it could still muster some 133,000 men and 587 guns with which to fulfil the Emperor’s commands. Having decided as a matter of honour to hazard a battle before Moscow, Kutusov was prepared to mount an obstinate resistance, sentiments he shared with the whole of the army. Unsure of where the French blows would fall would fall, he had spread his forces evenly over the whole front. On the extreme right he placed Platov’s Cossacks guarding the confluence of the Kalatsha and Moskva rivers. To their left were positioned Baggavout’s Second, Ostermann-Tolstoi’s Fourth, Uvarov’s First Cavalry and Korf’s Second Cavalry Corps all under the local command of Miloradovich. The centre was occupied by Doctorov’s Sixth Corps, its right resting on the heights of Gorki and its left on the great redoubt, supported by the Third Cavalry Corps of Kreutz, who had replaced the ailing Pahlen. Elsewhere the light infantry of the Second, Fourth and Fifth Corps occupied Borodino while the remainder of the Fifth Corps was held in reserve to the rear of the cavalry. To the left of Barclay’s First Army of the West stood Bagration’s Second. Raevski’s Seventh Corps was drawn up with its right in the great redoubt and its left resting on the village of Semionovskaya. Further left Borozdin’s Eighth Corps had its right behind Semionovskaya and its left occupying the flèches. Neveroski’s division occupied these, which together with Sievers’ Fourth Cavalry Corps, were under the local control of Gortchakov II. Finally on the extreme left Tutchkov’s Third Corps, together with the recently arrived Moscow militia, guarded the area around Utitsa. In all Kutusov had at his disposal 120,000 men and 640 guns with which to resist the French. Artillery Bombardment At 5:30 a.m. a gunshot rang out from a battery on the right of the French line to be answered immediately by the massed artillery of the Grande Armée. As Ney and Davout marched, with shot from a 120 guns thundering overhead, against the flèches it was to Eugène that the honour of first contact fell. Moving Morand’s and Gérard’s divisions across the Kalatsha to the right of Borodino, Eugène led Delzons’ division into the village. The attack was an overwhelming success however Delzons’ overeager troops rushed beyond the river and were themselves repulsed. Fortunately they were able to rally undercover of the village. Borodino being thus secured Eugène halted his corps d’armée to await developments around the flèches. On the right of the French line Davout was advancing along the margins of the wood preceded by his corps artillery. Having judged that sufficient ground had been made he turned to his left and, forming Compans’ division into columns of attack, advanced against the right hand flèche. No sooner had the division come within range of the Russian lines than a tremendous fire, both from the flèches and Woronzov’s grenadiers, assailed it. Their commander laid low by the first volley, the division began to waver but was rallied and led forward again, Teste’s 57eme Régiment d’Infanterie de Ligne taking the position at the point of the bayonet. The situation however was still critical with Woronzov’s grenadiers straining every sinew to regain the disputed position. At this point Ney entered the works with the division of Ledru and although they fought with the utmost fury the Russian grenadiers were driven back. Neveroski, hastening to the scene, rallied his compatriots and once more surged forwards. Nevertheless they were too late. Ney had now been joined by Marchand whose division, debouching to the left and right of the works, joined with those of Ledru and Rapp, Compans’ replacement, to drive off their Russian assailants. Meanwhile Ney’s third division, Razout’s, was engaging the left flèche in a struggle every bit as violent as that surrounding the right. From the first Bagration, who commanded the Russian forces in that part of the field, had realised that it was against him that the French were committing the bulk of their forces. Sending word to Kutusov of the impending collapse of his position, Bagration ordered forward the remaining grenadiers of Borozdin’s corps, a brigade of cuirassiers and the whole of Sievers’ Fourth Cavalry Corps. Directing these reinforcements against Razout’s division he drove the French from the captured entrenchment where they were attacked and driven from the hill by the Russian cuirassiers. Fortunately Murat was on hand with the division of Bruyère. Rallying the fugitive infantry he halted the cuirassiers advance and then counter-charged them with Bruyère’s light cavalry driving the enemy off in their turn. With this done Razout was once again able to occupy the Russian works. Meanwhile Ney had at last gained undisputed possession of the right flèche thus securing possession of the heights and enabling him to fire down on to the Russians. Bringing forward the artillery of the I, III and VIII Corps and the guns of the artillery reserve, Ney pour volley after volley on to the green ranks below. The Russians with their numerous artillery soon answered this fire. While Ney with the divisions of Ledru, Marchand, Rapp and Dessaix, Davout having been injured in the struggle for the earthworks, advanced on the right, Murat resumed the offensive on the left with the divisions of Razout and Bruyère. Approaching the ravine of Semionovskaya, the French took the third flèche in the rear but then came under a heavy and sustained fire from Raevski’s Seventh Corps on the other side of the ravine. Having no infantry to hand Murat brought forward Latour-Maubourg’s corps with orders to overrun the offending guns. Charging across the shallow valley the French cavalrymen met with some success but having no support were soon driven off. While these events were taking place around the flèches Morand’s division had advanced against the great redoubt. Marching in a cloud of smoke, which at least offered some protection from the numerous guns firing at them, Morand’s troops approached the redoubt unperceived. Nearing the enemy the 30eme Régiment d’Infanterie de Ligne charged, driving off its adversaries at the point of the bayonet. Meanwhile the remainder of Morand’s division debouched to the left and right of the great earthwork. Scarcely four and half hours had elapsed since the first guns had fire but already prestigious numbers of men had already fallen prey to the ferocity of the conflict. Nevertheless the French had made great progress. Borodino, the great redoubt and the three flèches had all been taken, while Rapp, Dessaix and Nansouty were making progress on the right. Only Semionovskaya remained to the Russians. One last great push and the Russian centre would have been irrevocably lost. Hastening to the Emperor, Murat’s chief of staff, Belliard, pleaded with him to release the army’s reserve but to no avail. Deep inside hostile territory Napoleon was unwilling to release the Imperial Guard and instead assigned only Friant’s division of the I Corps to Belliard. On the other side of the hill Kutusov was also receiving numerous demands for reinforcements. Acquiescing these pleas the Russian generalissimo released elements of Constantine’s Fifth Corps and the whole of Baggavout’s Second Corps to the centre and left. At the same time he authorised Uvarov and Platov to cross the Kalatsha and make a diversionary attack on the French left. Meanwhile Barclay and Bagration had to fend for themselves. Sending word for Eugen of Württemberg to speed his march on Semionovskaya, Barclay ordered his chief of staff, Yermolov, to rally the remnants of Raevski’s corps and retake at all costs the great redoubt. Borrowing a division from Doctorov, Yermolov stormed forward ejecting the 30eme Régiment d’Infanterie de Ligne from their hard won trophy. At the same time Korf and Kreutz launched their cavalry against the remainder of Morand’s leaderless, he had earlier been wounded, division with great success. The Russians had reoccupied the great redoubt but at great cost, Yermolov was severely wounded and the corps of Raevski almost totally destroyed. Meantime Barclay had arrived with Eugen’s division and, seeing the redoubt taken, had placed them on the edge of the Semionovskaya ravine. There they remained while projectiles from the artillery of Ney’s corps and the horse artillery of the guard tore great holes in their ranks. Bagration, having received Konovnitzin’s division of the Third Corps and elements of the Fifth, resolved to retake the flèches. Uniting these forces to the grenadiers of Borozdin’s corps and Sievers’ Fourth Cavalry Corps he once again advanced. However the task ahead of him was formidable. On their left Ney and Murat had Friant and Latour-Maubourg, in the centre the divisions of the III Corps and to the right Rapp, Dessaix, Nansouty and the VIII Corps. Murat had also brought Montbrun’s II Cavalry Corps into line. Plunging into the ravine Friant, leaving Semionovskaya unoccupied, drove all before him before being halted by a formidable fire from the opposite slope. Meantime Bagration with the grenadiers of Borozdin and Konovnitzin’s infantry had charged Ney. Here the combat reached new heights of savagery as both sides fought with increasing desperation. Seeking to end the conflict at a single blow Murat ordered forward the flower of the French cavalry, the cuirassiers. The order given four divisions of the heavy cavalry, St. Germaine and Valence from the I together with Wathier and Defrance from the II, bore down on their victims. A furious melée ensued with quarter neither asked for nor given. Montbrun fell mortally wounded pieced by a bullet, Rapp received yet another wound and was obliged to quit the field, Dessaix hastening to take command of Rapp’s division was also struck down, while on the left Friant was also wounded. The Russians also suffered sorely. Bagration, who thus far had escaped injury even though he had always been where the fighting was hottest, fell mortally wounded and was carried from the field. The movement of Friant’s division and the constant pounding of Eugen’s and Raevski’s troops was at last having an effect. Sensing that another opportunity had arisen to deal the Russians a fatal blow, Murat and Ney once again sent word to Napoleon for reinforcements. Concurring the Emperor ordered the Young Guard and Claparede’s division forward. At that moment though a great tumult was heard on the left. Having made a long detour Uvarov and Platov had at long last fallen on the rear of Eugène’s corps. Cancelling his forward movement Napoleon released the remaining artillery of the guard to Murat and awaited news from his left flank. From his vantage point at Schivardino Napoleon could clearly see large numbers of French fleeing on his left. Hastening to the scene Eugène was heartened to see Delzons’ veteran infantry calmly forming square and that only his baggage and light cavalry had been put to flight by the Russian onslaught. Falling on each of Delzons’ regiments in turn the Russian cavalry was driven off; unable to break the well ordered French infantry. Nevertheless as they retired across the Kalatsha, having suffered only minor losses from musketry and the sabres of Ornano’s returning light cavalry, Uvarov and Platov could be well satisfied with the result of their demonstration. They had delayed any further advance of the French by an hour. Profiting by this delay Kutusov had reinforced the Semionovskaya sector with the whole of Ostermann-Tolstoi’s corps. Seeing the opportunity to strike Semionovskaya slip away Napoleon ordered that the great redoubt be taken at any cost. The time was now 3 p.m. and although there were still considerable resources available to Eugène and Murat with which to fulfil the Emperor’s wishes many of the frontline units of the Grande Armée had suffered horribly, losing thousands of men and many superior officers. On the right of the proposed assault, at the edge of the ravine of Semionovskaya, Friant’s division still kept its position despite the constant attention of the Russian artillery. Alongside and behind this division Murat had ranged in a single battery the 200 guns with he had been provided. Behind them the II, III and IV Cavalry Corps waited to take advantage of the inevitable carnage the guns would cause in the Russian ranks. To the left of the cavalry Eugène had concentrated the divisions of Morand and Gérard to strike the right of the redoubt while the relatively fresh division of Broussier was to strike the left. To oppose this mass of men Kutusov had positioned the whole of Doctorov’s corps in and behind the redoubt while to their left were; the remnants of Raevski and Eugen; Ostermann-Tolstoi’s corps, and the cavalry of Korf and Kreutz. At the appointed time the signal to attack was given and the air was rent with the shriek of flying metal as balls from the 200 guns of the French grand battery found ready targets in the packed ranks of the Russian infantry. At length, deeming the Russians sufficiently shaken, Murat ordered forward the II Cavalry Corps, now under the command of Général Auguste Caulaincourt. Pouring across the ravine the cuirassiers and carabiniers of Wathier and Defrance drove all before them. Finding themselves in the rear of the great redoubt the 5e Cuirassier Regiment, with Caulaincourt at their head, turned abruptly to the left and fell on the redoubt from its unprotected rear. The great redoubt was once again in French possession but at the cost of Caulaincourt’s life. Advancing against the left of the redoubt the troops of Broussier, observing the bobbing helmets of Caulaincourt’s cuirassiers, broke into a run and entered the redoubt through the embrasures killing all those that had not already fallen victim to the heavy cavalry. While Caulaincourt and Broussier had been occupying the redoubt the remainder of the II Cavalry Corps had engaged in a bitter struggle with the cavalry of the Russian Guard. Charging and counter-charging the advantage had swung first to the Russians and them to the French. Eventually Grouchy had intervened, finally gaining the ground for the French. With the redoubt gained Murat passed the ravine thus forming a continuous line in the rear of the original Russian positions. In an effort to regain the initiative, Kutusov ordered that a counterattack be made by the Fourth, Sixth and, as yet unused, Fifth Corps against Semionovskaya. The French reacted to the danger in time and, with the help of 80 guns from the artillery reserve, repulsed the attack. Although shaken the Russians had managed to establish a new line on the next ridge. Without reinforcements, the Emperor was still steadfastly refusing to commit the Imperial Guard; the French were unable to hazard an attack on these new positions. At 6 p.m., after twelve hours of attack and counterattack, the fighting began to die down as exhaustion took its toll on the combatants. The remaining hours of daylight were taken up with an artillery dual between the protagonists. While these events had been taking place in the centre of the field Poniatowski’s Poles had been engaging Tutchkov’s Third Corps in their own private battle. The Poles had begun their advance early in the morning and by 8 a.m. were engaging Tutchkov’s grenadiers around a mound situated just to the east of Utitsa. The Russians, weakened by the detachment of Konovnitzin’s division to the flèches, hung on grimly until the arrival of Olssufiev’s division of the Second Corps restored some equilibrium to the sector. At noon Tutchkov ordered a counter-attack that drove the Poles back beyond the village but cost the Russian commander his life. Determined to retake the disputed village Poniatowski ordered his artillery to bombard the Russian positions until, at 4 p.m., the Russians were finally driven from Utitsa and its mound. As night fell the soldiers of both armies, exhausted with fatigue, sought repose. At their respective headquarters Kutusov and Napoleon were taking stock of reports from the front. The Grande Armée had suffered appallingly. Some 9,000 men had been killed and 21,000 wounded. Among the dead were Generals Montbrun and Caulaincourt while some eleven généraux de division had been wounded. Meanwhile Kutusov was contemplating renewing the conflict much to the astonishment of Barclay. However as the extent of the Russian losses, some 44,000 casualties including Bagration and Tutchkov killed, became apparent Kutusov ordered a retreat. As dawn broke on the 8th September the Russian army began to slip away leaving Miloradovich to delay the pursuit of the victorious French. Napoleon's Eagles (Part 3) Invasion of Russia 1812

Battle of Borodino Interregnum and Retreat Battle of Vinkovo Jumbo Map of Battle of Borodino (extremely slow: 372K) Napoleon's Eagles (Part 2) Invasion of Russia 1812

Battle of Smolensk Sideshow: Oudinot's Dvina Campaign First Battle of Polotsk Volhynian Summer Jumbo Map of Battle of Smolensk (very slow: 278K) Napoleon's Eagles (Part 1) Invasion of Russia 1812

From the Niemen to the Dvina Battle of Saltanovka Maneuver of Vitebsk Battle of Ostronovo Maneuver of Smolensk Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire # 80 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 2004 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com |

7th September 1812

7th September 1812