Napoleon’s Eagles (Part 2)

Russia 1812

Maneuver of Smolensk

by Kevin Birkett, FINS, Eire

| |

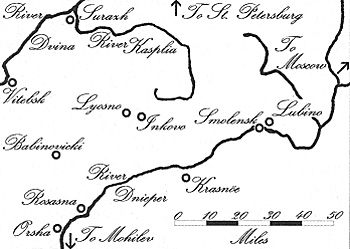

Following the failure of his attempt to outflank Barclay’s First Army of the West on the Dvina, and of Davout’s operations against Bagration, Napoleon decided to grant his forces a period of repose before embarking on the next phase of his offensive. Taking up residence in the governor’s palace of Vitebsk, he positioned his corps d’armée about him. In Vitebsk itself he placed the Imperial Guard; further up the Dvina at the small town of Surazh he stationed Eugène’s corps, while towards Lyosno, in the middle of the space between the Dvina and the Dnieper, and behind a curtain of wood that lines the banks of the River Kasplia, was Ney’s III Corps screened by whole body of Murat’s cavalry. The three detached divisions of the I Corps, under the command of Mouton, were in Babinovicki, while the remainder of that corps together with its commander, Davout, was in Orsha having ascended the Dnieper from Mohilev. To Davout’s south the other corps under his command, the VIII Corps and Poniatowski’s V Corps, were on the road from Mohilev to Orsha. Meanwhile Grouchy’s cavalry was extended towards Mouton’s troops, Latour-Maubourg’s were slowly retiring from Bobruisk and Pajol’s light cavalry were observing Bagration as he made his way to Smolensk. The Grande Armée was in dire need of the rest Napoleon had granted it. Since crossing the Niemen on the 24th June much of its manpower had melted away. Ney’s III Corps could only muster 22,000 of the 36,000 who had crossed into Russia; St. Cyr’s VI Corps had lost over half its strength, while the V and VIII Corps had each lost 8,000 men. Even the army’s best corps were not immune. The Imperial Guard had been reduced by some 9,000 men to 28,000 while Davout’s I Corps was down to 53,000 from 72,000. While granting his troops some rest from their labours, Napoleon continued his unabated. Although he could no longer keep the Russian armies apart it was still possible to prevent them from retreating into the interior of their vast country and to bring them to battle. The move the Emperor now envisaged was similar to that which had recently proved unsuccessful against Barclay. Using the curtain of woods that lined the Kasplia to shield its movement the Grande Armée was to move to its right, cross the Dnieper in the vicinity of Rosasna and Orsha and, ascending the left bank of that river, re-cross at Smolensk on the flank of the Russian armies. The distance to be traversed was great nevertheless, deeming the chances of success reasonable, Napoleon ordered Davout to prepare means of cross the river at the designated points. All was to be ready by the 10th August however before this plan could be put into operation the Russians struck. Barclay and Bagration had on the 4th August at last succeeded in uniting their armies under the walls of Smolensk. The general plan of the Russians thus far had been to retire before the French while remaining alert to the possibility of punishing any false manoeuvre by the French. Spurred on by faulty reconnaissance they now saw such a possibility. On the 5th Barclay called a council of war during which it was decided, over the objections of Barclay himself, to mount an operation against, what the Russians erroneously believed to be, the overly dispersed French cantonments. So it was that on the 7th August the First Army of the West, marching in two columns, departed Smolensk for the upper Kasplia while the Second Army of the West guarded its left flank. On the morning of the 8th the 12,000 strong advance guard of Barclay’s army, Platov’s Cossacks and Pahlen’s Third Cavalry Corps, surprised Sebastiani’s 3,000 light cavalrymen at Inkovo forcing them to take refuge with Ney. Meeting unexpected opposition from Ney, the Russians halted. This was not the only surprise to befall Barclay’s columns. Reports were beginning to reach Russian headquarters of considerable masses of infantry to their right in the direction of Surazh. Ordering his columns to break contact with the enemy Barclay directed a reconnaissance on his right believing that the French were attempting to turn that flank. Napoleon, receiving news of the baffling Russian movements on the 9th August, made preparations to suspend his own offensive and concentrate the Grande Armée at Lyosno. For twenty-four hours all was in readiness for the long awaited battle however as the 10th wore on it became apparent that Barclay was in fact retiring. Disappointed by the turn of events Napoleon reverted to his original plan. On the morning of the 11th the Grande Armée broke from its cantonments and advanced on the Dnieper. Leading the advance the corps of Murat and Ney, accompanied by General Eblé the engineer, made good progress towards Rosasna where they were to construct two bridges. By the evening of the 13th the first formations were able to cross the completed bridges and by the morning of the 14th some 175,000 men were on the left bank of the Dnieper, the troops under Davout’s command having crossed the river on the bridges they had previously constructed at Orsha. The first part of Napoleon’s had been achieved, he had succeeded in crossing the Dnieper unperceived by Barclay who was still engaged in fruitless attempts to locate the French on his right. Advancing ahead of the rest of the Grande Armée Murat’s corps soon encountered the enemy. When Barclay had commenced his ill-conceived offensive Bagration had detached Neveroski’s division of the Eighth Corps to Krasnöe as protection against any possible descent on Smolensk by Davout. It was this division that now stood between the Grande Armée and success. Grouchy and Ney, leading the advance guard, soon drove Neveroski through the town. However having cleared the town they were confronted by a ravine and a broken bridge which, requiring repair, halted the advance of Ney’s corps and all the artillery. Meantime Neveroski had formed his division into a huge square and was retreating down the tree-lined road to Smolensk. Descending the stream Grouchy’s troopers succeeded in discovering a ford; the chase was on. Time and again the French cavalry charged the Russian column but, protected by the trees and possessing artillery which the French did not, each time they were repulsed. In this way the Russian retreat proceeded for some distance until it reached the relative safety of the defile at Korytnia. Seven thousand men had succeeded in delaying the Grande Armée for the loss of just 1,800 of their number. Much of the 15th August was spent allowing the rear units of the Grande Armée to close up and celebrating the Emperor’s birthday. Meanwhile Grouchy and Ney cautiously continued their advance on Smolensk with expectations of finding it virtually undefended. At 3 a.m. the following morning, mounting the hills that surrounded the ancient walled city, their hopes were dashed. There below them, clearly perceivable in the growing light, could be seen a vast column of men entering the city on the other side of the Dnieper. The force that the French had seen was Raevski’s Seventh Corps, which had been sent there in haste by Bagration in answer to Neveroski’s urgent summons. For the next forty-eight hours Smolensk’s Russian defenders endured assault after assault from the forces that girdled the city before finally abandoning the ancient frontier fortress of Muscovy to the French. Entering the fire-ravaged city on the morning of the 18th August Napoleon was overcome by a profound melancholy. Three times he had now attempted to out manoeuvre the Russians only to see them slip away. Climbing a tower that flanked the Dnieper he could clearly see the Russians preparing to evacuate the northern suburbs and rejoin their compatriots who had already disappeared over the horizon. Instructing Ney and Eblé to re-establish the vital bridges, he ordered Junot, who had been elevated to the command of the VIII Corps on the 15th, to scout the river to the east of the city in search of a practicable ford. With that done he retired to await developments. At length the bridges were repaired and during the night of 18th and 19th August the corps of Ney passed the river in pursuit of the Russians. Driving off the Russian rear guard the marshal ascended the heights and was there presented with a dilemma. In the distance he could clearly see the Russians retiring down two roads. But which should he take? Following his decision to abandon the southern suburb of Smolensk Barclay had lingered on the right bank unable to decide whether to retreat or, as some of his generals wished, to continue the fight. It was only in the late afternoon of the 18th that, with the French bridges nearing completion, he decided to order a retreat. Bagration was the first to move off, retiring down the Moscow road Unfortunately Barclay had so delayed his decision that his own army was unable to follow the road taken by Bagration, which, running for six miles alongside the Dnieper, way prey to a flank attack by the French. To counter this Barclay planned to retire north on the St. Petersburg road before regaining the route to Moscow by crossroads. The decision made Barclay divided his army into two columns and commenced his retreat. The first column, under the command of Doctorov and consisting of the Fifth, Sixth, Second Cavalry and Third Cavalry Corps, had the widest detour to make, regaining the Moscow road at Solovievo a days march from Smolensk. The second column, under Tutchkov and consisting of the Second, Third, Fourth and First Cavalry Corps, had a much shorter diversion, gaining the Moscow road at Lubino. To prevent this column being anticipated at Lubino Barclay detached a mixed division along the main road to delay any French advance. From his vantage point on the hills overlooking Smolensk Ney could see the result of these various orders. Unable to discern the direction the main body of the Russian army was taking he took the bull by the horns and launched his corps pell-mell up the St. Petersburg road against the nearest enemy formation. Initially Ney had considerable success however the obstinate defence of Eugen of Württemberg soon halted his progress. Arriving on the scene some hours later Napoleon, discerning that the general direction of the Russian troops was towards Moscow, halted Ney’s attacks and ordered him to march immediately on the vital crossroad at Lubino. Marching with all possible haste Ney overtook Tutchkov III’s division at Valutino. The Russians, well aware of the consequences of failure, resisted manfully. As the day worn on each side threw more men into the struggle but although they eventually became masters of the field the French were unable to prevent the passage of Tutchkov’s column. On hearing of the scale of the conflict Napoleon hastened to the scene. Arriving at 3 a.m. on the 20th August he was left to rue another opportunity lost. He had failed to encircle Bagration’s army, he had failed to outflank Barclay’s army on the Dvina, he had failed to outflank the combined Russian armies on the Dnieper and now he had failed to prevent the retreat of a major part of Barclay’s army. As he rode back to Smolensk the Emperor had many thoughts on his mind. He had clearly outmanoeuvred the Russians at every turn and yet they remained undefeated. No enemy had ever eluded him so. Clearly he could not allow the Russians to escape but to follow them was to conform to their plan of campaign. His next decision could well decide the fate of his empire. Napoleon's Eagles (Part 2) Invasion of Russia 1812

Battle of Smolensk Sideshow: Oudinot's Dvina Campaign First Battle of Polotsk Volhynian Summer Jumbo Map of Battle of Smolensk (very slow: 278K) Napoleon's Eagles (Part 1) Invasion of Russia 1812

From the Niemen to the Dvina Battle of Saltanovka Maneuver of Vitebsk Battle of Ostronovo Maneuver of Smolensk Napoleon's Eagles (Part 3) Invasion of Russia 1812

Battle of Borodino Interregnum and Retreat Battle of Vinkovo Jumbo Map of Battle of Borodino (extremely slow: 372K) Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire # 79 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 2004 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com |

29th July to 20th August 1812

29th July to 20th August 1812