Napoleon’s Eagles:

Russia 1812

Maneuver of Vitebsk

by Kevin Birkett, FINS, Eire

| |

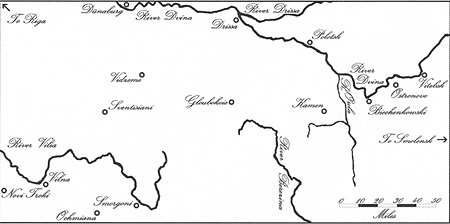

28th June to 28th July 1812 Having dispatched Davout to deal with Bagration, Napoleon once again turned his attention to Barclay’s First Army of the West. At the first eruption of the Grande Armée on to Russian soil Barclay, in conformity to the agreed pre-war plan, had fallen back to his prepared entrenched positions on the left bank of the River Dvina at Drissa. The camp itself was situated in a deep recess formed by the river at that point between which its designer, the Prussian general Phull, had ordered two lines of immense fortifications built, each bristling with numerous artillery. Only a part of Barclay’s army was required to man the mile long works, the remainder provided a formidable reserve. Should a retreat be ordered the camp was provided with four bridges to the right bank. Although an impressive position, the camp at Drissa was far from invulnerable, a circumstance that Napoleon soon perceived. Having entered Vilna on the 28th the Emperor proposed to spend some ten days reorganising his army, already ravaged by the long march across Europe and the storms that accompanied the invasion, before leaving for the front on the 9th July. After leaving Vilna he intended, while Oudinot and Ney occupied Barclay’s attention, to cross the Dvina with Murat’s cavalry, Eugène’s and Mouton’s infantry and the Imperial Guard in the vicinity of Polotsk, turn north and cut off Barclay from St. Petersburg and Moscow. By the 10th final orders had been issued. Ney was ordered to move to his left on Vidzeme while the Imperial Guard and Mouton advanced on Gloubokoie and Eugène moved from Novi Troki on Kamen by Ochmiana and Smorgoni. Meanwhile to safe guard his communication he ordered Victor, who commanded the IX Corps at Berlin to advance on Danzig and Augereau, who’s incomplete XI Corps was stationed on the French borders, to replace him in the Prussian capital. As the French columns hurried down the dusty Russian roads Napoleon’s master plan was already beginning to go awry. Ever since the plan to hold the French on the Dvina had been conceived there had been much disquiet among the Russian hierarchy. Many of the senior commanders, partly resentful of the influence a foreign general had over the Tsar, had openly intrigued to abandon the camp and retreat deeper into the recesses of the Russian countryside and trust to mother nature the task of whittling away Napoleon’s numerical superiority. At length those intrigues produced fruit. Flattered by his generals’ insistence that his presence was vitally needed in Moscow to raise the morale of the capital and plagued by doubts about the suitability of the camp, the Tsar called a council of war. After much debate the Russian generals won the day. The camp at Drissa was to be abandoned and the army was to march on Vitebsk and Smolensk. With the die finally case Barclay issued the necessary orders and on the 19th July the First Army of the West, marching along both banks of the river, began its move to the upper reaches of the Dvina. Although this movement brought Barclay’s army closer to that of Bagration and covered Moscow it, at the same time, uncovered St. Petersburg. To counter this unwelcome development Barclay detached Wittgenstein’s First Corps to cover the Dvina between Riga and Polotsk. For the next three days the march continued unmolested, however such a movement across the front of the Grande Armée could not for long escape the attention of Murat’s probing cavalry. News of the Russian move reached the Emperor on the 22nd. By that time Eugène had reached Kamen as ordered. To his left were situated Murat and Mouton while further left still were the corps of Ney and Oudinot. Meanwhile the Imperial Guard had reached Gloubokoie. Although his original plan had been made redundant Napoleon quickly saw that there was still a chance of enveloping the Russians if he could anticipate them at Vitebsk. Reacting with his customary zeal, orders were immediately issued for the army to rendezvous at Biechenkowski, aside that is from Oudinot who was ordered to cross the river at Polotsk and protect the army’s rear. The next day Eugène, having crossed the River Oula, occupied Biechenkowski. On the opposite bank he could clearly see Doctorov’s rear guard while to his front were numerous detachments of Russian cavalry. Having only an advance guard with him Eugène was forced to await the arrival of the remainder of his corps by which time Nansouty’s cavalry and the Emperor had arrived in the town. Apprised of the situation Napoleon quickly concluded that, if the Grande Armée could increase its pace, it would still be possible to interpose himself between Barclay and Bagration. Without waiting for the remainder of his army, which was still half a march to the rear, he ordered that Murat, accompanied by Nansouty’s and Eugène’s corps, should march on Ostronovo at dawn on the following day, the 25th July. Meantime Barclay, who had come to the same conclusion as Napoleon, had placed Ostermann-Tolstoi’s Fourth Corps in advance of Ostronovo to delay the French advance. A clash was now inevitable. Setting out early on the 25th Murat’s advance guard, Bruyère’s light cavalry, soon discovered elements of Ostermann-Tolstoi’s cavalry on a slight eminence in advance of Ostronovo. Driving off the enemy cavalry and breasting the hill they were met with the sight of the whole of the Russian Fourth Corps drawn up in order of battle. For the remainder of the 25th and into the 26th the tenacious defence of Ostermann-Tolstoi’s troops held Murat’s forces back. When at last they broke though it was to late; Barclay had made good his escape towards Smolensk. Having entered Vitebsk unopposed on the 28th July and pursued the Russians throughout the remainder of the day without ever overtaking their rear guard or even encountering the usual debris associated with a retreating army, Napoleon summoned Murat and Eugène. The Grande Armée was in a deplorable state. The weather throughout this latest advance had been oppressively hot. Many of the army’s inexperienced conscripts had fallen out and even the veterans of Egypt made unfavourable comparisons with that far-away country. In addition to the stragglers Napoleon had also lost St. Cyr’s VI Corps, which had been left in Biechenkowski to act as a link with Oudinot. Aware that Davout had failed to prevent Bagration’s march on Smolensk and with his army requiring a period of rest, Napoleon called off the advance. The manoeuvre of Vitebsk had ended in failure. Napoleon's Eagles (Part 1) Invasion of Russia 1812

From the Niemen to the Dvina Battle of Saltanovka Maneuver of Vitebsk Battle of Ostronovo Maneuver of Smolensk Napoleon's Eagles (Part 2) Invasion of Russia 1812 by Kevin Birkett

Battle of Smolensk Sideshow: Oudinot's Dvina Campaign First Battle of Polotsk Volhynian Summer Jumbo Map of Battle of Smolensk (very slow: 278K) Napoleon's Eagles (Part 3) Invasion of Russia 1812

Battle of Borodino Interregnum and Retreat Battle of Vinkovo Jumbo Map of Battle of Borodino (extremely slow: 372K) Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire # 78 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 2004 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com |