Napoleon’s Eagles (Part 3)

Russia 1812

On the Road to Moscow

by Kevin Birkett, FINS, Eire

| |

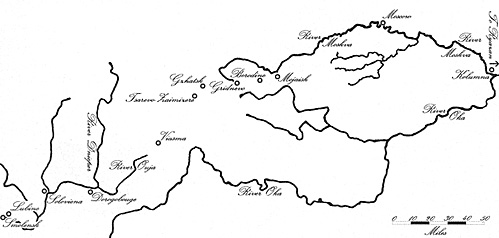

As Napoleon rode back to Smolensk on the 20th August following the clash at Valutino many thoughts crowded in on his mind. Should he follow the retreating Russians or remain on the banks of the Dvina and Dnieper for the winter, reorganising his army and recruiting troops in newly liberated Poland? If he advanced could he protect his flanks? Could his armies defend the frozen river lines in the depths of a Russian winter if he remained on the Dvina and Dnieper? How would the rest of Europe view a winter spent in Smolensk, would it be seen as a defeat or the prudent action of a great commander? How could a vast empire that stretched from Cadiz to the wastes of Russia be ruled from Smolensk? Should he quit the army and if so who could command it in his absence? These were questions of great consequence affecting not just the fate of the Grande Armée but also the empire. Nevertheless while deliberating on these matters Napoleon had more routine matters to attend to. Following their narrow escape at Valutino the Russian armies continued their orderly retreat towards Moscow, impeding the progress of Murat’s and Davout’s shadowing forces at every opportunity. Taking advantage of the terrain Barclay’s rear guard would delay Murat’s cavalry until the arrival of Davout’s infantry and then retire, under cover of Russian cavalry, to the next favourable position. In this way the Russians withdrew; crossing the Dnieper at Soloviena and continuing onwards until the 22nd when, under pressure from his subordinates, Barclay halted at Dorogobouge to give battle. Arriving on the 23rd Murat and Davout deemed the Russian position, between Dorogobouge and the River Ouja with their right resting on the Dnieper, to formidable to tackle alone. Perceiving however that the position could be turned and the Russians trapped in the angle of the Ouja and Dnieper they ordered Poniatowski, who had been advancing to the right of the advance guard, to position his Poles at the source of the former and sent word to Napoleon. Napoleon received the news from Dorogobouge on the 24th and immediately resolved to punish Barclay for his temerity. Ordering Eugène, who had been advancing on the left of the army, to join Murat and Davout, he departed Smolensk with the remainder of his forces. Travelling through the night with his escort he arrived at sunrise on the 25th before the Russian positions. However he was to be disappointed for in the meantime the Russians, perceiving the weakness of their position, had retired towards Viasma. Although undecided when he left Smolensk, having crossed the Rubicon, Napoleon finally concluded that his best chances for success lay in an advance on Moscow. On the 26th August orders were issued and the Grande Armée set out on its fateful march towards the Russian capital. The move on Moscow however was not made without some regard to the ever-lengthening lines of communication and to the flanks of the Grande Armée. Naming Smolensk as the new base for the army Napoleon ordered Victor to march on that city there to join Delaborde’s division, which had been left in the city when Napoleon had departed for the front. Meanwhile Augereau was ordered to position his corps, in echelon, between Danzig and Berlin; Grenier was ordered from Italy to Augsburg and Dombrowski, earlier detached from the V Corps, to Mohilev. With these precautions taken the Grande Armée set out. Murat with the cavalry of Nansouty and Montbrun together with the light cavalry of the I and III Corps formed the advance guard. Next came Davout, then Ney, Junot and the Guard. To the right at a distance of ten miles marched the corps of Poniatowski and Latour-Maubourg while on the opposite flank, at a similar distance marched Eugène and Grouchy. In all some 145,000 men were marching on the Russian capital. On the 28th the vanguard of this imposing force entered Viasma, two days later it passed through Tsarevo-Zaimizeze and the following day, the 31st August, entered Gzhatsk. The march from Dorogobouge to Gzhatsk, while proceeding with very little combat, had cost the French a considerable number of men. Realising that a major battle could only be a matter of days away Napoleon ordered his corps d’armée to halt to allow stragglers to rejoin the colours and for accurate role-calls to be taken. Napoleon’s premonition of the immanency of a major battle was all too accurate. Much had changed in the Russian army since it commenced its retreat. The loss of Smolensk and the near disaster at Valutino had resulted in a bitter war of words between Barclay and his nominal subordinate Bagration. As the retreat continued many junior offices had not alone joined in the criticisms of Barclay but had also railed against the influence of foreigners in the army. With morale falling and the clamour for Barclay to be replaced growing evermore strident the Tsar resolved to appoint a commander-in-chief to the combined armies of Barclay and Bagration. Kutusov The man chosen for this onerous task was General Mikhail Hilariononvich Golenichev Kutusov. Kutusov had arrived at the army, together with Bennigsen his chief of staff, on the 29th August while it was preparing to give battle at Tsarevo-Zaimizeze. Disapproving of the ground he immediately ordered the retreat to continue. Kutusov had in fact already chosen the ground on which he would hazard a battle with the advancing French. So it was that the combined Russian armies passed through the small village of Borodino and over the River Kalatsha, taking up positions in the angle formed by that river and the River Moskva. There they awaited the arrival of the French. At noon on the 4th September, having recuperated from their labours, the troops of the Grande Armée once again took to the road. Resting that night at Gridnevo they set out again at dawn the following morning. As the day progressed ever-increasing numbers of enemy horsemen presaged their arrival before the Russian positions. As evening approached the Russian army could be seen clearly across the plain drawn up in order of battle. Unwilling to mount a frontal assault on the Russian positions around Borodino, Napoleon inclined his troops slightly to the right so that he could cross the Kalatsha and deploy on the plain in front of Kutusov’s entrenchments unmolested. Unfortunately Kutusov had foreseen this development and had constructed an advanced redoubt at Schivardino, some 1,500 yards ahead of the main Russian positions, to counter just such a move. Summoning Murat and Compans, Napoleon ordered the advance guard to clear the redoubt. The day was already well advanced when, Murat’s troopers having dispersed the enemy squadrons, Compans’ infantry advanced in dense columns. Ahead of the redoubt there was a small ridge on which Compans established a battery in order to silence the enemy’s artillery. After a brisk cannonade Compans’ troops advanced against the Russian positions. Advancing, initially under cover, the French infantry suffered increasingly from the fire that belched forth from the troops in the redoubt and those flanking it. Fearing further losses in this unequal exchange of gunfire Compans ordered his men to storm the position at the point of the bayonet. Answering the call, General Teste’s 57eme Régiment d’Infanterie de Ligne charged up the last few yards separating them from the enemy’s embrasures driving all before them. However the Russian commander in the area, Gortchakov II, seeking to relieve Neveroski’s hard-pressed division committed the whole of the Eighth Corps to the struggle. The grenadiers of the Eighth Corps soon retook the disputed redoubt but by then French reinforcements were beginning to arrive. Morand, advancing on Compans left took the village of Schivardino and Poniatowski’s Poles were turning the southern flank of the redoubt. The final acts of this sanguinary clash were played out in total darkness, with Murat charging the Russian rearguard as it retired towards the main positions, however in the gloom the Russians escaped. If Napoleon needed reminding of the task that faced him the fight for possession of Schivardino provided it. The French lost some 4,000 men while the Russians sacrificed 6,000 defending the exposed position. Both sides spent the 6th positioning their troops for, what Napoleon hoped would be, a decisive encounter the following day. In the event the 7th proved to be a big disappointment for the Emperor. As the day wore on the battle developed into a series of frontal assaults against the well-entrenched Russians, with both sides suffering appalling casualties. With night falling the French settled down ready to renew the bloody struggle the following day. However the Russians had other ideas and during the hours of darkness resumed their retreat towards Moscow. In the early hours of the 8th Kutusov, leaving Miloradovich his rearguard commander to defend Mojaisk for as long as possible, continued his eastwards movement. Before long the French were once again on their trail, entering Mojaisk on the morning of the 9th. On the 13th the Russian army, by now only numbering some 50,000 men, established itself at the gates of Moscow and there awaited the arrival of the French. As usual there had been much argument within the army during the retreat regarding the wisdom of defending Moscow. Calling a council of war Kutusov solicited the views of his senior officers. Bennigsen, Ostermann-Tolstoi, Yermolov and Konovnitzin were all in favour of a desperate defence of the capital, whereas only Barclay advocated further retreat. Nevertheless it was to Barclay that Kutusov listened. So it was that on the night of the 13th/14th the Russian army defiled silently through the streets of Moscow and took the road to Ryazan, from which it would be possible, having broken contact with the French, to gain the road to Kolumna and the abundant supplies of the south. Meanwhile the Grande Armée was advancing rapidly towards the heights from which they hoped to gain their first view of Moscow. At length, from the summit of a hill, they beheld the vast city laid out before them while in its centre could be seen the Kremlin, the ancient home of the tsars. Ordering Murat to secure the gates Napoleon awaited the inevitable delegation of citizens pleading for their city to be spared. He was to be disappointed. Entering the city Murat found the streets deserted and the city inhabited only by foreign families, escaped criminals and thousands of Russian wounded. Furnished with these details Napoleon’s joy at beholding the object of his labours turned to profound disappointment. Unwilling to enter the city in the dead of night he delayed his entry until the following day. On the morning of the 15th September Napoleon, accompanied by a glittering array of senior and staff officers, entered the deserted streets and took up residence in the Kremlin. However the 100,000 men of the Grande Armée that entered the city in his wake gave ample evidence of the hardships of a campaign in which the enemy was yet to be defeated. Napoleon's Eagles (Part 3) Invasion of Russia 1812

Battle of Borodino Interregnum and Retreat Battle of Vinkovo Jumbo Map of Battle of Borodino (extremely slow: 372K) Napoleon's Eagles (Part 2) Invasion of Russia 1812

Battle of Smolensk Sideshow: Oudinot's Dvina Campaign First Battle of Polotsk Volhynian Summer Jumbo Map of Battle of Smolensk (very slow: 278K) Napoleon's Eagles (Part 1) Invasion of Russia 1812

From the Niemen to the Dvina Battle of Saltanovka Maneuver of Vitebsk Battle of Ostronovo Maneuver of Smolensk Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire # 80 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 2004 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com |

20th August to 15th September 1812

20th August to 15th September 1812