Threatened by strong Austrian pressure on both flanks, the battle could escalate into disaster for the French unless these moves were quickly countered. Lusignan posed a threat, but Quasdanovitch and Wukassuvich were much more serious problems. If the main Austrian army could reach the plain at the top of the Osteria gorge, the entire right flank of the French line would be rolled up.

Threatened by strong Austrian pressure on both flanks, the battle could escalate into disaster for the French unless these moves were quickly countered. Lusignan posed a threat, but Quasdanovitch and Wukassuvich were much more serious problems. If the main Austrian army could reach the plain at the top of the Osteria gorge, the entire right flank of the French line would be rolled up.

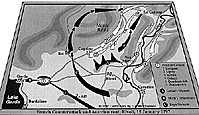

Large Version of Map: (slow download: 87K)

Quickly, Bonaparte prepared to parry the Austrian advance. The 39th were rallied and formed into column. Six hundred cavalry under Leclerc, who had just arrived, were brought up to the right of the 39th. Two battalions of the 14th Demi-brigade were given the task of retaking Monte Magnone which was swarming with Ocksay's Croats. They would then turn their fire on the Austrian troops moving up through the gorge below. Everywhere else along the line, the French would go over to the defensive.

As noon approached, Quasdanovitch noticed that Monte Magnone had been cleared of French troops and prepared his own assault. He could clearly see the danger to the French right. He brought up his infantry supported by six squadrons of cavalry. This force would throw out the rest of the French troops from the gorge and fall upon the flank of Bonaparte's army. The Austrian artillery, still positioned across the Adige river, continued their cannonade, but their fire had less and less effect the farther up the gorge they had to fire. As a result, they could offer little support to the Austrian columns.

The Austrian assault moved up the gorge and began to emerge onto the flat ground between Monte Magnone and the hill of Rivoli. In front of them, less than a mile away, the right flank of the French army loomed through the cannon smoke. Just then, the French artillery opened up and raked the Austrian column with murderous accuracy. Skirmisher fire against the Austrian right revealed that Monte Magnone had fallen to the French again. Suddenly, emerging from the cannon smoke on the Austrian left front, Leclerc's cavalry bore down upon the Austrian troops. Their own cavalry, struggling up the gorge, did not have time to deploy.

Leclerc's charge had a great impact despite its small size: only 600 troopers. The sudden appearance of this cavalry, however, riding down upon the white-coated Austrians, set off a panic among the leading elements of Quasdanovitch's column. At this same moment, an Austrian powder caisson was struck by a shell, exploding with a deafening impact. The head of the Austrian column collapsed and fell back, causing panic among the troops who were still coming up the gorge. In a moment, the Austrians were reduced to a mass of fugitives fleeing back down the gorge. Leclerc's cavalry was in among them, driving them on towards the Adige.

The threat to the French right had been averted. The Austrian infantry had emerged onto the plain without artillery support or cavalry to guard its flanks against a foe that enjoyed the benefits of these combined arms. The result was catastrophic for Quasdanovitch's column.

An Orderly Austrian Retreat Turns Into Disaster

Despite this success, the French still had to contend with one last Austrian column. By 1:00 P.M. Lusignan had successfully driven the French 18th Demi-brigade from Affi and placed his troops across the highway leading south to Castelnuovo. Bonaparte ordered the 75th to turn and face south. The 75th had been placed in reserve, except for two battalions which were used to flesh out Joubert's line after the 85th fled. The 18th, which had been driven back relentlessly by Lusignan, was still ready for action, and it was brought up to support the 75th. Bonaparte addressed the 18th Demi-brigade next to which he watched the action: "Brave 18th, I know you! The enemy cannot stand before you!"

Massena then addressed his men:

"Comrades, in front of you are 4,000 young men belonging to the richest families in Vienna; they have come with post-horses as far as Bassano: I recommend them to you!" According to Massena, it was the young Louis Bonaparte who gave the 18th and the 75th the time to turn against Lusignan. Louis, returning from Peschiera (he was an aide-de-camp to his older brother Napoleon) temporarily delayed Lusignan's advance by throwing a squadron of the 15th Dragoons against them and turning a battery of artillery onto the compact Austrian column. This gave the 75th and the 18th time to deploy and move against the Austrians.

Meanwhile, General Rey was advancing up the highway from Castelnuovo behind Lusignan's line with the 58th Demi-brigade. The Austrians, who had hoped to cut off the French line of retreat, now found themselves in a similar peril.

Lusignan, however, remained calm. As the 75th and 18th deployed into battalion columns and the 1st Cavalry Regiment moved up to exploit any French success that might develop, Lusignan slowly and deliberately withdrew towards Affi and Costermano. The French continually attempted to close in around his flanks, but he succeeded in holding them off.

The regimental history of the 18th Demi-brigade tells an interesting, but seemingly improbable, story that illustrates the demoralization that set in among some of the Austrian troops during Lusignan's retreat. The 18th had left a detachment of 45 men (some sources say 150 men) at Garda, a town on the shore of the lake, who were surrounded by 1,500 Austrians from Lusignan's command. The Austrians were attempting to retreat along the lake shore and decided to take the French along as prisoners. When ordered to surrender, Captain Rene, the French commander, answered by ordering the Austrians to surrender instead. Amazingly, the Austrians did so. Two flags were handed over to the 18th, while three others were thrown into the lake. This is not the only instance of French troops bluffing the Austrians into laying down their arms. During the campaign of Castiglione in August of 1796, Bonaparte supposedly captured another Austrian column in much the same way.

Apparently, the brave Captain Rene and his 45 men, as well as a column of around 600 men from the 12th Light Demi-brigade (commanded by Murat) which had crossed to Garda by boat, sealed Lusignan's fate. These two forces, small as they were, succeeded in cutting off the Austrians' line of retreat. Near the shores of Lake Garda, Lusignan surrendered his command, and over 4,000 men fell into French hands.

Alvintzy and his staff had come up to Caprino during the early afternoon, and around 2:00 P.M., he began to rally Koblos's, Ocksay's and Liptay's men at the foot of Monte Baldo. They still held Caprino and the slopes of Monte Baldo. Also, he had moved several battalions around for another assault on Monte Magnone. Even with the disasters that had befallen his men, his casualties had been relatively slight.

The columns that had come over Monte Baldo were tired, hungry, and bloodied, but they were still intact. He ordered Quasdanovitch to transfer several battalions over the steep slopes of Monte Baldo to La Corona and then to descend into the plain of Rivoli. Even at this late time, he could mount a credible assault on the Trombolare heights. But, after surveying his troops, he decided to let them rest and attack on the 15th.

Although Bonaparte contemplated following up on his success by moving against Alvintzy's remaining troops, he received word that Provera had eluded Augereau and crossed the Adige at Anghieri. If Bonaparte did not act quickly, Mantua would be relieved and all of the bloodshed below Monte Baldo would be for naught.

One can imagine the thoughts of the men of the 18th and 75th Demi-brigades as Massena rode up and ordered them south to Roverbella. They had marched all night from Verona, fought at Rivoli, and were now going to march as quickly to the defense of Mantua. Only Bonaparte could request, and receive, such efforts from his men. After an all too brief rest, the demi-brigades marched off south.

Bonaparte followed them, leaving Joubert to finish the battle. Joubert's advantage over the Austrians was not certain. The most reliable demi-brigades were filing off to the south. His own men had suffered heavily in the fighting of the last several days. The 85th Demi-brigade was only now recovering its nerve. But Joubert was expected to drive Alvintzy back across Monte Baldo.

Alvintzy's Army is Shattered, Mantua Captured

The 15th saw the resumption of the battle and the defeat of Alvintzy. Joubert's troops performed remarkably well. Alvintzy's Austrians, half-starved, put up a brief resistance before retreating in a disorderly mob up Monte Baldo. Alvintzy, with a small party of troops, made a stand for awhile, but seeing that he was being outflanked, retreated. Joubert thus completed Bonaparte's work. The Austrians lost nearly 2,000 casualties over the two days. However, some 12,000 prisoners added to the magnitude of the defeat.

Augereau, smarting from his failure to stop Provera from crossing the Adige, was working to rectify his mistake. He assaulted the bridge at Anghieri with 7,000 men and captured the troops that Provera had left to guard it. Augereau then moved west in an attempt to catch Provera as he moved on Mantua. The Austrians, who had spent the night of 14-15 January at Nogara (about half-way between Anghieri and Mantua) were still moving on Mantua. They arrived at St. George, a suburb of Mantua, around noon. Unfortunately, this position was held by General Miollis and 1,500 entrenched Frenchmen.

Finding St. George too powerful to attack, Provera began to shift his men south towards La Favorita, another suburb of Mantua that guarded the southern causeway. This was also in French hands. Still, Provera was able to get word into Mantua to Wurmser letting him know that he was outside the city. Accordingly, Wurmser prepared a sortie to be executed the next morning. Provera settled down outside La Favorita to await the 16th.

All during the day on the 15th, Massena sped south with his demi-brigades. Augereau was moving west. Provera and Wurmser's decision to wait for the morning of the 16th was fatal because it gave time for Bonaparte's converging columns to arrive before the siege could be broken. As the sun rose on the 16th, Provera and Wurmser launched their attacks. Serurier held, and soon Massena and Augereau arrived to encircle Provera's men. Provera had no choice and surrendered with all 6,700 men.

Joubert's conclusion to Rivoli and Provera's surrender outside Mantua brought the campaign of January 1797 to a victorious end for the French. The third Austrian effort to relieve Mantua had failed. There would be no further attempts. Wurmser would hold out until 2 February and then surrender his survivors, a further 15,000 men captured by the French.

With the fall of Mantua, Bonaparte completed his conquest of northern Italy. He moved south against the Papal forces and forced the Holy Father to accept the Treaty of Tolentino on 19 February which gained 30 million francs for the Directory. In spite of the battlefield disasters of the past ten months, and the fall of Mantua, the Austrians were determined to continue the war. They began to create a fifth army, under Archduke Charles, to send against Bonaparte.

What followed in the final stages of Bonaparte's first campaign in Italy will be explored in the next issue of Napoleon.

More Rivoli

-

Rivoli: Introduction and Situation

Opening Moves Confuse Napoleon

French Success Turns Into Misfortune

French Counterattacks Reverse the Course of Battle

The 200th Anniversary Series on Napoleon in Italy

-

First Installment: Side Road To Immortality

Second installment: The Supporting Cast

Third installment: Maintaining the Initiative

Fourth installment: General Bonaparte Defends His Conquests

Fifth installment: Napoleon Turns Defeat into Victory

Sixth installment: One Final Victory: Rivoli

Seventh installment: Endgame: The Pursuit to Final Victory

Eighth installment: Instrument of Victory: Army of Italy

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #7

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by Emperor's Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com