Fourth in a series on Napoleon in Italy.--RL

General Dagobert Sigismond Count Wurmser was the third Austrian commanding general to be defeated by Napoleon Bonaparte since the latter took command of the Army of Italy at the end of March 1796. The first to succumb to the 27-year-old Corsican's forces was General Michael Colli's Sardinia-Piedmontese army. After knocking Sardinia-Piedmont out of the First Coalition, formally completed by the Armistice of Cherasco, Napoleon turned upon General Johann Peter Beaulieu's force.

Beaulieu, hoping to avoid a major battle, had his rearguard overtaken in the famous storming of the bridge at Lodi on 10 May. The 71-year-old Beaulieu was dismissed after his cordon defense was smashed by the French at Borghetto on 30 May 1796. After this defeat, the Austrian hold on northern Italy consisted solely of the fortress of Mantua, soon put under siege.

In an astonishingly rapid two-month campaign, General Bonaparte took his starving brigades from a thin strip of coastland around Genoa, and led them as they fought their way through the daunting Apennine mountains and onto the fertile plains of northern Italy. Along the way, through an audacity that continues to astonish the student of military history, he neutralized two enemy field armies by dividing them and defeating them in detail. In addition to resupplying his army, his victories placed the lucrative coffers of Milan and Venice at the disposal of an impoverished French Republic. He had, as few leaders have before or since, succeeded in making war pay for war.

Beyond his logistical and battlefield brilliance, Napoleon's political ingenuity surfaced. In what is arguably one of history's most persuasive publicity campaigns, General Bonaparte orchestrated a continuing series of propaganda bulletins aimed not only at his own soldiers but also at the people of France. This included a piece of artwork showing Napoleon leading the charge across the bridge at Lodi, adding heroic embellishment to his factual accomplishments.

Despite these self-promotions, Napoleon would soon prove again that he was a formidable soldier. In July, a new Austrian army under General Wurmser arrived in the theater with the objective of relieving Mantua and retaking the valuable territories of northern Italy. Once again, Napoleon utilized a superior central position to defeat a divided opponent at the twin battles of Lonato and Castiglione on 3 and 5 August, 1796 [see Maintaining the Initiative in Napoleon magazine #4]. The old Austrian hussar Wurmser, who had served the Austrian cause since 1747, now led the retreat north with his portion of the army to the east of Lake Garda. Meanwhile, General Peter Quasdanovitch marched the battered remains of his command up the west side of the lake and then around the north end to rejoin Wurmser.

In the interim, Napoleon put the fortress of Mantua once more under siege and took his main force up the Adige valley to face the defeated but still sizable Austrian army. It had been the original intent of Napoleon's superiors in the Directory to have the Army of Italy advance past Trent up the Brenner Pass and move into southern Germany to support the Republic's main field armies under Jourdan and Moreau.

In the interim, Napoleon put the fortress of Mantua once more under siege and took his main force up the Adige valley to face the defeated but still sizable Austrian army. It had been the original intent of Napoleon's superiors in the Directory to have the Army of Italy advance past Trent up the Brenner Pass and move into southern Germany to support the Republic's main field armies under Jourdan and Moreau.

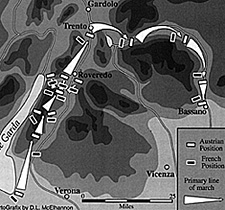

However, as Napoleon moved north on the Austrian position near Roveredo on 3 September, he found that Wurmser had taken most of his army and slipped east trying to move around the French in order to relieve Mantua. Wurmser was in the Brenta valley and heading south toward Verona as Napoleon advanced.

At this point, Napoleon took yet another well-calculated risk. Instead of heading back down the Adige valley trying to outpace Wurmser to Verona, he decided to first crush Quasdanovitch in order to secure the Army of Italy's line of communications. Then, he would follow behind Wurmser's army with the hope of pinning the Austrians against Kilmaine's garrison at Verona.

The French attack of 4 September was two-pronged. The vanguard of General Vaubois' division, commanded by the capable General St. Hilaire, stormed the bridge at Sarca, while Massena's advance elements under General Pigeon overwhelmed Wukassovich in the defile of San Marco. As both Austrian flanks gave way during the engagement, Bonaparte ordered his cavalry under Dubois to charge the fleeing enemy and administer the coup de grace. The pursuit caused an Austrian rout, but General Dubois was killed in the confusion.

The fleeing Austrians passed through Roveredo and only halted at the formidable position of Calliano. This pass was a very narrow defile, only about 200 feet wide, further strengthened by the castle of La Pietra, which the Austrians had bolstered with several guns. This position would squeeze any sizable attacking force approaching it, creating a large target. If permitted time to augment their defense, the Austrians might not be extricated without resorting to a veritable siege.

Napoleon recognized the need to attack while the Austrians were still disheartened. His first step was to find a commanding position for his cannon in order to pound the Austrians at the point of attack, including a bombardment of the old castle. As Napoleon's guns were taking their toll, French skirmishers climbed the steep hillside and began to snipe at the outflanked enemy below. When the combined fire was showing its effect, Napoleon sent forward an assault column of nine battalions straight toward the center of the narrow defile; the troops surged forward, densely packed. The first volley of the Austrians nearly dropped the entire front rank of French infantry, but the inspired Republicans continued to shove forward, coming to grips with the Austrians. The castle fell in the first rush and the remaining defense gave way rapidly.

Napoleon recognized the need to attack while the Austrians were still disheartened. His first step was to find a commanding position for his cannon in order to pound the Austrians at the point of attack, including a bombardment of the old castle. As Napoleon's guns were taking their toll, French skirmishers climbed the steep hillside and began to snipe at the outflanked enemy below. When the combined fire was showing its effect, Napoleon sent forward an assault column of nine battalions straight toward the center of the narrow defile; the troops surged forward, densely packed. The first volley of the Austrians nearly dropped the entire front rank of French infantry, but the inspired Republicans continued to shove forward, coming to grips with the Austrians. The castle fell in the first rush and the remaining defense gave way rapidly.

Many demoralized and exhausted Austrians surrendered; others were forced back into their own cavalry. Because the nature of this confined fighting precluded the easy passage of lines, the retreating troops tended to disorder those behind them, and the rearward momentum that commenced at the front became infectious. The confused intermixing of retreating infantry with the cavalry held in reserve made both forces virtually useless, and panic evidently ensued among the Austrian ranks. Fifteen cannon were captured during this chaos along with numerous standards. All Austrian resistance was swept away.

The French then pushed further north, and on 5 September Massena entered Trent, Wurmser's original base of operations and famous City of the Councils. The final Austrian resistance in the area was broken on the morning of 6 September at Lavis, five miles north of Trent, at which point Napoleon took the bulk of his army through the pass entering the Brenta valley, and pursued the unsuspecting Wurmser.

Wurmser wrongly believed that Napoleon would take his main army up the Adige River and through the Brenner Pass and link up with the French armies operating in the Danube valley. Hoping to take advantage of the presumed absence of Napoleon, Wurmser dispatched a division under Meszaros to seize Verona, an action which would open the way to the relief of the Austrians bottled-up in Mantua. There he planned to combine with the garrison, and, thus reinforced, he hoped to reassert control over northern Italy.

Napoleon, however, left only a small division under Vaubois to secure the Brenner Pass and then chased down the Austrian rearguard at Primolano, some 30 miles east of Trent. He hoped to catch the Austrians between the Brenta and the Adige rivers, or at least, to force Wurmser to retreat to the northwest and thereby abandon Meszaros.

The lead elements of Napoleon's force, General Augereau's division, came upon two Austrian battalions, made up mostly of Croats, in a position which might normally be judged unassailable. But the French were flush with victory, reinvigorated with the supplies captured at Trent. Augereau sent forward the 5th Light Regiment deployed as skirmishers backed by three battalions of the 4th Line Infantry Regiment, commanded by future Marshal Jean Lannes, formed in columns.

The assault unhinged the right flank of the Austrians and with perfect timing, Napoleon sent in the 5th Dragoons under General Milhaud. The French cavalry swept around to the rear and cut off the defenders from their line of retreat. Some fled while the majority surrendered. By evening the French bivouacked around the town of Cismone, six miles south of Primolano. The French claimed 4,200 prisoners, 12 cannon, and 5 standards.

Meszaros in the mean time stood stymied before Verona. Kilmaine had fortified the city and his thirty guns had been more than enough to throw back the white coated attackers. Dissuaded by his losses, Meszaros called for reinforcements and bridging equipment in order to begin a formal siege. Wurmser received this disappointing request at virtually the same time as news of the disaster to his rearguard. Prudently, he recalled Meszaros to help face the French onslaught bearing down on him from the Brenta valley. Regrettably for Wurmser, Meszaros would arrive too late to be of any assistance.

The battle of Bassano on 8 September started with an assault on the Austrian vanguard of six battalions that were positioned in a gorge bisected by the Brenta River. These troops were driven back on the main Austrian line, where Wurmser was astonished to realize that he was being attacked by Napoleon's main force which had not gone north as he had hoped. The Austrians were tenuously deployed in front of Bassano, with Quasdano-vitch on the left bank of the river in front of the town, and Sebottendorf on the right bank guarding the bridge, held with artillery and grenadiers.

Massena's division attacked the right bank, while Augereau's division hit the left. Both assaults succeeded in putting the Austrians to rout. As the Austrians fell back through the city of Bassano, only the old covered bridge linked the two wings of the Austrian forces. Its possession now represented complete victory for the French. Once again the 4th Line was selected to lead the assault. Colonel Lannes and Massena, under whom the 4th was temporarily serving, stormed the bridge in the face of a desperate final defense.

Despite being wounded, Lannes not only continued to lead his regiment forward, but also, incredibly, he was credited by Napoleon with personally capturing two Austrian standards! In the face of such audacity and courage, the dispirited Austrian resistance collapsed. Quasdanovitch's force, now severed from the rest of the army, retreated east toward the Piave. Napoleon sent in the cavalry to exploit and crown the success of his infantry, and Murat executed this mission with aplomb.

At days end, 6,000 prisoners, 8 colors, 32 cannon, 2 pontoon trains, and over 200 wagons were reported as taken. The pitiful remains of Wurmser's once large army of more than 50,000 men retreated south to join Meszaros with only 16,000 men under arms (including 3,500 relatively fresh cavalry not employed because of unsuitable terrain for Austrian mounted tactics).

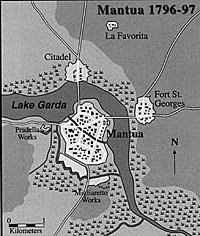

Increasingly desperate, Wurmser gambled that he could break through to relieve Mantua. He moved south, luckily finding the bridge at Legnano undefended, the French detachment having evacuated the position as a result of a false report. Wurmser and the Austrians continued toward Mantua and were successful in a couple of skirmishes when they turned upon their overextended pursuers. By 12 September he had reached Mantua after brushing aside the French covering force.

He intended to collect all but a small garrison and break out, probably in the direction of Sacile. Unfortunately for these plans, his garrison guarding the crossing of the Adige at Legnano capitulated on 13 September. By the afternoon of the 14th, the towns to the north and northeast of Mantua were in French hands. Once again, the city was effectively besieged.

Wurmser had one advantage, which was that he held the fortified tete de pont of Saint-Georges on the primary causeway over the lake and onto the left bank of the Mincio River. From here he launched his attack of 25,000 men against General Bon's division (Bon had replaced the ailing Augereau on the 13th). The Austrian dual assaults at Saint-Georges and La Favorita caused relatively heavy casualties to both sides. The Austrians, knowing this was their best chance to break out of a grim situation, fought with determination.

The French, meanwhile, having taken great care in their dispositions, triumphed in the end when Massena's division, centrally positioned and concealed by the nature of the rolling terrain, came up and attacked. Massena's men, led in part by Victor, fell upon an Austrian center weakened in response to the ferocity of Bon's attack on the Austrian right flank near Vigol and Castelletto. Acts of sang froid also aided the French cause, such as when the 18th Line Infantry Regiment coolly checked an Austrian cuirassier attack by firing a steady volley from line (rather than, as many would expect, by forming square). The telling blow was delivered by Marmont leading a battalion of the 18th and a provisional grenadier battalion to seize Saint-Georges. The defeated Austrians retreated over the causeways and inside of the city walls.

The victory over Wurmser was now complete. 22,000 total soldiers were trapped inside malaria-riddled Mantua, suffering the effects of hunger and disease (this included the pre-existing garrison).

A master of maintaining and building morale, an appreciative Napoleon showered awards and promotions upon the deserving French soldiers. But General Bonaparte and his exhausted army would have but a short respite to bask in the glow of this brilliant phase of the campaign. All too soon, the Army of Italy would be called to face yet another Austrian army, this one assembled under General Josef Alvintzy, which would arrive on the scene in November.

Despite defeating three armies in less than six months, Napoleon and his soldiers would have to find the fortitude to face a fourth Austrian army. The most daunting part of the Italian campaign in 1796-1797 remained ahead.

The 200th Anniversary Series on Napoleon in Italy

-

First Installment: Side Road To Immortality

Second installment: The Supporting Cast

Third installment: Maintaining the Initiative

Fourth installment: General Bonaparte Defends His Conquests

Fifth installment: Napoleon Turns Defeat into Victory

Sixth installment: One Final Victory: Rivoli

Seventh installment: Endgame: The Pursuit to Final Victory

Eighth installment: Instrument of Victory: Army of Italy

About the author

Todd Fisher is the CEO of Emperor's Press, which published Napoleon magazine. He is also the Executive Director of the Napoleonic Society of America. This is the fourth installment of an ongoing series begun in issue #2 promoting the Napoleonic Era's bicentennial.

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #5

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1996 by Emperor's Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com