Defeating four seperate armies and three major relief attempts directed at the fortress at Mantua, 27-year-old General Bonaparte had reached a pinnacle of success in less than a year. But the Austrians were as determined as they were ill-starred. Yet another army would be sent to Italy; this time it would be led by the gifted Archduke Charles, fresh from triumphs of his own in Germany. One day Archduke Charles would defeat Napoleon. However, Charles would have to wait twelve years to accomplish this at Aspern-Essling [see Napoleon #3]. In this campaign Bonaparte would prove unstoppable.

Following the victory of Rivoli (15 January 1797) and the capture of Mantua (2 February 1797), Bonaparte turned his attention to completing his strategic goals. To achieve this end, he had to finish pushing the Austrians out of Italy, and then mount a serious threat to Vienna. Hopefully these events would bring the Austrians to the point of surrender.

Directory Hesitant

The Directory remained hesitant to give significant support to a General who had turned a secondary theater of war into a triumphant platform that now posed a large threat to their very political existence (no doubt they were rather uncomfortably reminded of a young Caesar). Unable to come to terms with the strategic significance of Bonaparte's impressive achievements, the Directory doggedly continued to place great hope upon the Republican armies on the Rhine. If the anticipated ultimate victory could be a result of the combined push of multiple armies, credit would not have to be given to one general.

Furthering Bonaparte's difficulties, the Austrian War Council had sent their best general, Archduke Charles, the victor of Neerwinden (18 March 1793) and brother of the Austrian Emperor Francis, to oppose him. In 1796-97, Charles had successfully stymied the Republic's vaunted offensive across the Rhine. The Austrians hoped that the Archduke could reverse their fortunes in Italy.

Bonaparte's main advantage was that the large Austrian reinforcements which were scheduled to accompany the Archduke, numbering over 30,000, lagged behind: The Austrian War Council, in its wisdom, had insisted that the French bridgeheads over the Upper Rhine, at Kehl and Huningue, be taken. This gave Bonaparte yet another momentary opportunity to achieve local numerical superiority over the Austrians. Bonaparte's command numbered over 55,000 after reinforcement by Bernadotte's division of 7,000. In the immediate theater of operations, he would possess an overall numerical superiority over the Austrians, who numbered, according to Phipps, only about 40,000.

Wasting no time, Bonaparte divided his command into two wings: he left three divisions under Joubert to watch the Adige approaches to the north, and he kept four divisions, with another division following to act as a reserve. Bonaparte planned to advance to the northeast with this body of nearly 35,000 men and drive the Austrians before him out of Italy.

The first action of the final phase of the campaign was the taking of the town of Foy by Murat's advance guard on 23 February 1797. This opened the Piave Valley, where Bonaparte promptly directed Massena's 1st Division to advance north toward Fortogna while he moved east for the Tagliamento River with the main body of three divisions. The 9,000 men of Massena's command were to remove the 3,600 Hapsburg troops under Lusignan as a threat; otherwise, Lusignan would be able to descend the Piave and fall upon the main French supply line.

Fortified Position

Massena found the Austrians in a very strong position at the town of Fortogna. The fortified position was protected by mountains on one flank and the Piave River on the other. On 13 March, Massena launched his infantry in a frontal assault while his dragoons, still mounted, waded into the river. The water was shallow enough that the dragoons could pass round and gain the Austrian flank.

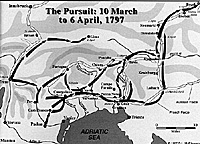

Bonaparte reached the Tagliamento River on 16 March and his entire command waded across catching the Austrians unprepared. This action would set the tone for the remainder of the war. The Archduke was always kept off balance by Bonaparte's ability to continually seize the initiative and confound Austrian plans and expectations.

The main French force reached the fortress of Palma Nova on 18 March and split once again. Bernadotte, whose men had previously served in the Rhine theater and were regarded as rivals by most of the Army of Italy, headed east toward Gradisca. Meanwhile, the remainder of the army headed north up the Isonzo valley with Guieu's (formerly Augereau's) division in the lead.

In the meantime, Massena had reached Sacile on 16 March, and then turned north following the Tagliamento. He was opposed by Ocskay who held the position at Chiusa. Once more the fort looked to be unassailable, but the intrepid French light infantry was able to climb over the mountain peak and descend upon the flank of the position. Finding that they had been turned, Ocskay's men fell back on the town of Ponteba. This position was soon assaulted and the retreat continued toward Tarvis. It was here that Charles had hoped to group his army for a major counter-attack. He had three columns heading that direction. Bayalitsch was moving up the Isonzo Valley from the south, Charles was coming from the southeast from Krainburg, and Ocskay was retreating from the west.

Massena Pushes Too Fast

The problem for Charles's scheme was that Massena was pushing too fast from the west. Ocskay's men were bundled out of Tarvis and soon Massena's men held the head of the three valleys. It would be a race. The question was whether Charles could bring up enough forces to bear to crush Massena before Bayalitsch was caught, in turn, between Massena and Bonaparte.

On the morning of 22 March, Massena learned that Austrian troops coming from the south had attacked and taken Tarvis. He launched an immediate counter-attack and retook the ground. Bayalitsch's men were under attack from the head of Guieu's division from the main French body. The situation was desperate for Bayalitsch; Charles personally led a cavalry charge to try to relieve the pressure. In a vicious struggle, Massena's men held their ground. Bayalitsch's remaining men then surrendered as Bonaparte was threatening to annihilate them in the narrow gap.

The French victory at Tarvis was the last major attempt to give battle by the Archduke. What followed was a series of rearguard actions as the Austrians retreated toward Vienna. Massena's division took the lead on the pursuit accompanied much of the time by Murat's cavalry. There were several actions at Klagenfurt, Dirnstein, Neumarkt, and Leoben. Finally as the French approached within striking distance of Vienna, the Austrians requested an armistice on 7 April 1797.

Bonaparte had pushed his army to the limit of its supply line, but he had never permitted his opponent a respite. By the time of the armistice, Joubert had joined up with the rest of the French army after a harrowing time fighting the Austrians and Tyroleans near Brixen. His troops would be needed as a revolt in Venice occurred on 12 April in which many French were massacred. The Venetians had been pushed to extremes by the demands of both opposing armies. The Directory's rapacious levies on theoretically neutral territory ignited the situation. If Joubert's troops had not been available, the French supply line would have been cut. As it was, the rebellion was quickly and ruthlessly put down, and Venice would pay by losing her long-standing independence.

Treaty Negotiation

As his army settled down, Bonaparte busied himself negotiating a treaty that, technically speaking, he had no authority to conclude (this audacity did nothing to calm the insecurities of the Directory). Bonaparte's bluff was nearly called when the Austrians suddenly agreed to sign the Preliminaries of Leoben (18 April 1797). This agreement led directly to the Peace of Campo Formio (17 October 1797). Among its terms, Austria ceded Belgium and northern Italy, and by secret clause, conceded the left bank of the Rhine to France.

At right, George Cain painting: "Bulletin of Victory from the Armies of Italy 1797," which purports to show Parisian citizens' reactions to Gen. Bonaparte's successful conclusion to the Italian campaign. Note old style Revolutionary flags and gentleman in foreground suggesting concern of many who feared Bonaparte's ambition.

As one of these noted historians, David Chandler, wrote:

"In many ways the Italian Campaign marks the end of an era. The days of limited eighteenth-century warfare were fast drawing to a close in the face of the energy and ideology of the French Revolutionary armies, now led for the first time by a general really worthy of their latent talents. For this period marks the emergence of one of the greatest captains of all time. In March 1796 Napoleone Bounaparte was known only to comparitively restricted circles within France, but a year later his name had become a household word throughout Europe....the young eagle had found his wings; the future lay with Destiny."

The 200th Anniversary Series on Napoleon in Italy

Despite his relatively continuous string of battlefield victories, Bonaparte had to surmount several remaining difficulties before realizing his full aims. Perhaps foremost among them, the Army of Italy was tired following the exhaustive strain of a year of campaigning.

Despite his relatively continuous string of battlefield victories, Bonaparte had to surmount several remaining difficulties before realizing his full aims. Perhaps foremost among them, the Army of Italy was tired following the exhaustive strain of a year of campaigning.

Some Austrian hussars rushed to intercept them, but were soon defeated ending a rather unusual cavalry river action. The startled Austrians were horrified to discover that they were now effectively surrounded. Many were able to break out, but Lusignan himself was captured (for the second time this campaign) in a rear-guard action a few miles north. With the destruction of Lusignan's command, the French turned east and climbed the mountain pass in an effort to reach Sacile.

Some Austrian hussars rushed to intercept them, but were soon defeated ending a rather unusual cavalry river action. The startled Austrians were horrified to discover that they were now effectively surrounded. Many were able to break out, but Lusignan himself was captured (for the second time this campaign) in a rear-guard action a few miles north. With the destruction of Lusignan's command, the French turned east and climbed the mountain pass in an effort to reach Sacile.

General Bonaparte's First Italian Campaign ranks in the handful which can be considered among history's greatest. From its commencement on 10 April 1796 to its conclusion almost exactly one year later, Bonaparte had propelled himself to the center of the European stage. Many historians speculate that even had Napoleon retired or been killed in 1797, he would still be considered one of the Great Captains, probably ranking somewhere just below Caesar, Hannibal and Alexander.

General Bonaparte's First Italian Campaign ranks in the handful which can be considered among history's greatest. From its commencement on 10 April 1796 to its conclusion almost exactly one year later, Bonaparte had propelled himself to the center of the European stage. Many historians speculate that even had Napoleon retired or been killed in 1797, he would still be considered one of the Great Captains, probably ranking somewhere just below Caesar, Hannibal and Alexander.

First Installment: Side Road To Immortality

Second installment: The Supporting Cast

Third installment: Maintaining the Initiative

Fourth installment: General Bonaparte Defends His Conquests

Fifth installment: Napoleon Turns Defeat into Victory

Sixth installment: One Final Victory: Rivoli

Seventh installment: Endgame: The Pursuit to Final Victory

Eighth installment: Instrument of Victory: Army of Italy

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #8

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by Emperor's Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com