Napoleon earned the sobriquet of "history's greatest captain" through the many brilliant campaigns he conducted. However, in 1796, Bonaparte was only a local hero in Paris, having crushed the royalist counter-revolution of 5 October with the famous "whiff of grape". Except for his success in assisting in the capture of Toulon from the British and Spanish in 1793 (which brought him to Paris), the young artillery officer had yet to prove that he was worthy of the rank of general de division (major general) bestowed on him by the grateful Revolutionary Council. Indeed, that same Directory was growing nervous of General Bonaparte's popularity. Perhaps if the young commander of the Army of the Interior were out of the way, literally; Italy might just be far enough away from Paris to muffle the ambitious Corsican.

Revolutionary France had been at war with Sardinia-Piedmont since 1793. At first it appeared that Sardinia would join the other First Coalition allies in overrunning France, but this threat had been beaten back in 1794 and the front was stalemated. The French won the battle of Loano in 1795 taking the Italian Riviera coast, but were unable to move inland since then. The troops were badly underfed and under equipped. Mutiny was a very real possibility. Into this situation the Directory thrust the young Corsican General [the politics behind this appointment will be examined in another article].

Napoleon arrived in Italy in early April. His plan for the campaign was to separate the Sardinian Army from its Austrian ally and defeat each army in detail. The allies held mountain positions and outnumbered the French three to two. In their strength lay their weakness, however. Because the allies were in the mountains they had little lateral communication, and thus the allies would have difficulty supporting each other.

When Napoleon arrived, he took measure of his army, addressed many of its pressing morale problems, and then formulated his plan. The two allied armies were commanded by Generals Beaulieu and Colli. Napoleon wanted to attack Beaulieu's Austrians and drive them back on their lines of communication away from Colli's Sardinians. But Beaulieu struck first, near the town of Voltri on 10 April, 1796.

While this development upset Napoleon's plans, he soon found a way to turn it to his advantage. This attack extended the Austrians even more. While Napoleon gathered his army to strike, Beaulieu attacked Laharpe's Division at Mount San Giorgio on 11 April. The French initially gave ground but finally held along the ridge top of Mount Negino. Napoleon was alerted and assembled his troops for a counter-attack the next day.

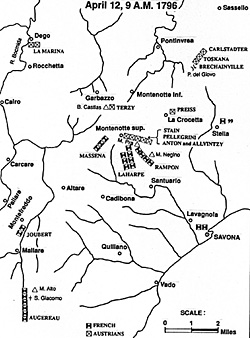

The morning of 12 April was foggy and the French were able to advance concealed. Laharpe's Division was divided into two columns, one under Col. Rampon and the other directly under Laharpe. As these two columns converged upon the Austrian position on Mount Pra, one of Meynier's Brigades (temporarily under Massena), moved around their right flank. Just as Laharpe was to contact General Argenteau's Austrians, the fog lifted. Argenteau could see that his position would be flanked. He ordered a withdrawal, but the French pursued. He fell back to a position around the town of Montenotte Superior, but was pushed out. The Austrian's position hinged upon holding the castle of Bric Castlas. Massena's men came on quickly and overwhelmed the battalion of Terzy, holding the castle. The Alvintzy battalion sent to their rescue was also defeated and a rout developed. Napoleon had won his first battle (Montenotte) as a commanding general.

But Napoleon encountered a major obstacle to his plans. The old castle of Cosseria had been occupied by General Provera with a Sardinian grenadier battalion and a couple of companies of Austrian infantry which were under Colli's command. Napoleon felt that in order to proceed against Colli, this position had to be taken. Augereau ordered his division to immediately assault the castle. The attack failed with heavy losses. But Provera was left low on food, water, and, most importantly, cartridges. He surrendered on the morning of the 14 April. The road was now open to Ceva, the main Sardinian camp.

While the castle was besieged, Massena advanced on Dego and found the town occupied by four battalions. Using a flanking attack, the town was surrounded and forced to surrender. A relief column of the Hoch and Deutchmeister, the finest line regiment in the Austrian Army, was stopped only by the greatest of efforts. Massena's starving men then started to forage; poor French logistics were making sustained operations extremely difficult. The French were still scattered the next morning when General Vukassovitch fell upon them with five battalions. He had been called to reinforce Dego, but confused his orders so that he arrived a day late.

Things were desperate for Massena and he called for Laharpe's men to hurry forward. Massena rallied his men for a counter-attack. Vukassovitch too called on nearby Austrian units, but they had been demoralized by the events of the last few days and failed to respond. As a result the French were able to retake Dego and put the outnumbered Hapsburg troops to flight. The Austrians fell back on their lines of communication and were not able to help Colli again.

On 16 April, Augereau's Division attacked 7,000 Sardinians in their camp of Ceva. The French attack was repulsed, but Napoleon suspected that if he could keep up the pressure on them the enemy would collapse. Colli, fearing he would be overrun, retreated, leaving a small rearguard. Napoleon surrounded it and consolidated his army for the next push.

For the next few days, the French followed Colli and fought a skirmish at San Michele, where they forced a bridgehead across the Corsaglia River. They found Colli deployed around the town of Mondovi on 21 April. Napoleon directed the divisions of Serurier and Meynier to attack both flanks of the Sardinian position. Serurier's attack crushed Colli's flank and he then attacked the heights overlooking the town in conjunction with Meynier's men. Pushed off the heights, the Sardinians fell back into the town where they were pursued by the French cavalry under Stengel. Substantial supplies were seized in the town, a very welcome surprise to the French. The victory came at a price; Stengel was mortally wounded by a Sardinian cavalry rearguard during the pursuit.

Larger Size (slow download--106K) of map at right.

Larger Size (slow download--106K) of map at right.

Bonaparte now turned his attention to the Sardinians. He knew from spies in the Sardinian court that they were weary of the war and felt that they had been encouraged to join the First Coalition by promises that had not been kept. A telling blow against them might shake their resolve and cause their surrender or defection. Toward that end, the main French forces were now arrayed against General Colli. The remaining French columns moved on from Montenotte and take Dego, which would isolate Colli from Austrian support.

Bonaparte now turned his attention to the Sardinians. He knew from spies in the Sardinian court that they were weary of the war and felt that they had been encouraged to join the First Coalition by promises that had not been kept. A telling blow against them might shake their resolve and cause their surrender or defection. Toward that end, the main French forces were now arrayed against General Colli. The remaining French columns moved on from Montenotte and take Dego, which would isolate Colli from Austrian support.

In less than a month,

General Napoleon Bonaparte had

taken command of his army,

fought five battles in a campaign

against superior overall odds.

Napoleon now marched on Turin, the Sardinian capital. The remnants of Colli's defeated Army could only follow and watch as Cherasco, the last defended position between the Revolutionary army and Turin, was overrun. Colli forced marched his army to get to a position to guard the capital, but the King of Sardinia-Piedmont had had enough. On 27 April, 1796 came the requested peace resulting in the Armistice of Cherasco on 28 April.

In less than a month, General Napoleon Bonaparte had taken command of his army, fought five battles in a campaign against superior overall odds, and had hammered a Coalition ally out of the war. He would next turn on the Austrians, attacking them at Lodi [see Brent Nosworthy's account of this battle beginning in this issue] and continuing his first, and possibly greatest, campaign.

While the Directory in Paris may have hoped that they would be able to consign General Bonaparte to obscurity in a secondary theater of the war, hindsight allows us considerable amusement at the enormity of their misjudgement. The legend was beginning.

Order of Battle: 1796 Italian Campaign (text--fast)

Order of Battle: 1796 Italian Campaign (graphics--very, very slow (356K))

The 200th Anniversary Series on Napoleon in Italy

-

First Installment: Side Road To Immortality

Second installment: The Supporting Cast

Third installment: Maintaining the Initiative

Fourth installment: General Bonaparte Defends His Conquests

Fifth installment: Napoleon Turns Defeat into Victory

Sixth installment: One Final Victory: Rivoli

Seventh installment: Endgame: The Pursuit to Final Victory

Eighth installment: Instrument of Victory: Army of Italy

About the author:

Todd Fisher is the CEO of Emperor's Press and the Emperor's Headquarters. He is also the Executive Director of the Napoleonic Society of America.

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #2

© Copyright 1996 by Emperor's Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com