Large Version of Map: (slow download: 108K)

As long as General Wurmser remained inside Mantua with his garrison, Bonaparte was not free to move north into the Tyrol or into Austria, thereby taking a possibly decisive hand in events transpiring across the Alps.

In Germany, the Archduke Charles had conducted a successful campaign against the French armies of the Sambre-et-Meuse and the Rhin-et-Moselle. The Directory, which ruled France, had hopes of ending the war in 1796. These plans miscarried on the Rhine frontier, and by the autumn of that year the two French armies were back on the Rhine.

The Directory determined that the time was right to open negotiations with the Emperor of Austria. The war against France was in its fourth year. France was weary of war and revolution, and the Directory wanted to consolidate its rule. General Moreau's campaign in Germany was still seen as the main French effort, and it had failed. Although Bonaparte's victories were impressive, they had not brought the war any closer to an end. Accordingly, the Directory hoped to bring the Austrians to the negotiating table separately from their British allies.

The Hapsburgs were not inclined to talk, however. Having the upper hand in Germany, they were determined to relieve Mantua and retake northern Italy. The Pope had been persuaded to break his agreement with the French, and Austrian officers had been sent to Rome to help train and lead the Papal forces. Wurmser was ordered to prepare to break out of Mantua and move south of the Po to link up with these forces as soon as possible.

Wurmser's situation in Mantua was far from favorable, however. Thomas Graham, a British officer assigned to Wurmser as a political liaison and observer, was in Mantua between September and the end of December 1796 (when Graham escaped). In his memoirs he leaves a startling picture of the state of affairs among the almost 32,000 men trapped in the city:

"...[The] troops had already suffered much from the intermittent fever that Mantua is annually exposed to during the autumn. The [men] soon exhausted the small stock of cattle, and it was found necessary very soon to reserve for the use of the hospitals all that remained of fresh beef or of wine, the army only then receiving bread as rations. It was soon evident that the quantity of forage was very inadequate to the support of such a great number of horses. An inspection, therefore, took place twice a week, and all those horses that seemed sinking under the scanty allowance of hay, were condemned to be slaughtered, and a distribution of a quarter-of-a-pound of horseflesh was daily made to all those soldiers who chose to accept it. Many at first declined, and particularly the corps of artillery, but by degrees all became willing competitors for this allowance."

Meanwhile the want of hospital stores increased the mortality rate; on some days the death toll reached 150, and was rarely under half that number. Few men sent to the hospital ever rejoined their units. Soldiers actually died at their posts, preferring to conceal their illness in order to avoid being condemned to the hospital, which they viewed as a warrant of death. Morale inside Mantua steadily declined as hope of rescue diminished with each passsing day.

The Austrian government was well informed of the gravity of the situation within the city. Accordingly, they were busy preparing a third attempt to relieve the fortress. If Wurmser could not break out, General Alvintzy, the Austrian commander in Italy, would come to his aid.

Baron Josef Alvintzy was 61 years old in January of 1797. Born in the eastern provinces of the Austrian Empire, he had served in the Hapsburg forces for over four decades. During the Seven Years War, he had participated in campaigns in Silesia against Frederick the Great. During the 1780s he had fought against the Ottoman Turks in the Balkans. In 1792, with the outbreak of the War of the First Coalition (as it would later be called), Alvintzy had been given command in the Low Countries where he had defeated the French at Neerwinden.

His record in Italy had been spotty at best. Like Beaulieu and Wurmser before him, Alvintzy had failed to dislodge Bonaparte from his hold on northern Italy. Alvintzy's greatest achievement had been to defeat Bonaparte at Caldiero in November during the second attempt to relieve Mantua. Unfortunately, he had failed to follow up this modest victory and had subsequently been rebuffed at Arcola. As a result, Mantua was not relieved and the Austrians withdrew east beyond the Piave River and north to Trent.

Austrian Plan

Alvintzy's plan for the coming campaign called for a move by concentric columns on Bonaparte's positions along the middle reaches of the Adige River. His plan was quite similar to those used in the Arcola and Castiglione campaigns, which called for a number of columns to descend from the foothills of the Alps to attempt to break through to Mantua. Both of those attempts had failed, but Alvintzy and the Hofkriegsrath, the Austrian War Council, had persuaded themselves that it was not the fault of the plan itself, but rather the number of men assigned to each column.

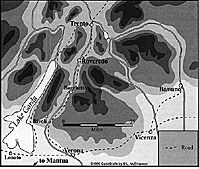

Accordingly, Alvintzy divided the Austrian army into three battle groups, each of which would assault the French from a different direction. From the east, two columns under Provera and Bayalitsch were to cross the Piave and advance on Legnano and Verona, respectively. These two columns, numbering around 14,000 men, would draw Bonaparte's attention away from the main drive, which would come down the Adige valley from Trent. Here, Alvintzy himself with just over 28,000 men would move on Verona by way of Monte Baldo and Rivoli.

The terrain between Lake Garda and the Adige River valley dictated how Alvintzy would distribute the forces attached to his column for the coming campaign. From the shores of the lake, the land rises swiftly to the 7200 foot summit of Monte Baldo, a massive bulk of mountain that divides the Adige valley from the lake. Monte Baldo is aptly named, for it is an essentially treeless eminence with large, rocky outcrops. In 1797, it could only be traversed by following a number of foot paths which led from north to south. These paths were dominated by the position of La Corona, a rocky sentinel that blocked all movement south and overlooked the Adige valley.

Beneath La Corona and Monte Baldo, the Adige River flowed down from the Alps hemmed in on the west and east by precipitous cliffs. The river wound its way from wall to wall, and was paralleled by two roads that ran on either side of it. The western road was no more than a track, but the eastern road was a major highway with a paved surface. No bridge crossed the river until Bussolengo near Verona.

Austrian Columns

Based on these considerations, Alvintzy decided to divide the troops under his personal command into six columns, each of which would have a different objective. The first four columns were about equal in size:

Column I, commanded by Lusignan, consisted of 4,556 men. It would advance by a foot path along the shore of Lake Garda to the little village of Lumini, which stood at the foot of Monte Baldo near Rivoli. By seizing Lumini, Lusignan would place himself in a position to cut off Joubert's retreat from La Corona or to turn Joubert's left flank should he fall back on Rivoli.

Column II, commanded by Liptay, consisted of 5,056 men. It would move directly over Monte Baldo against La Corona.

Column III, commanded by Koblos, consisted of 4,138 men. It would parallel Liptay's column by moving on an adjacent path over Monte Baldo. Its objective was La Corona also.

Column IV, commanded by Ocksay, consisted of 3,521 men. It would move through the Adige valley on the trail that ran down the west side of the river. Just below La Corona, the column would ascend the heights of Monte Baldo and take the French in the right flank. Ocksay would not, however, be able to climb the steep trail that led up to La Corona until Koblos and Liptay had secured control of the surrounding heights. As a result, Ocksay's column would remain on the valley floor until the position was taken.

Lusignan, Liptay, Koblos, and Ocksay would all be moving over the most rudimentary of mountain tracks. As a result, they would have to advance without artillery or cavalry support, and the men would have to carry their rations with them.

Column V, commanded by Quasdan-ovitch, was the strongest with 7,871 men. It would move, behind Ocksay, along the trail that ran on the west bank of the Adige. Quasdanovitch was to advance to the base of the Osteria gorge, then turn right and come up onto the plain of Rivoli along the right flank of the French line.

Column VI, commanded by Wukassuvich, was the smallest force with only 2,871 men: it had all the cavalry, the artillery, and military stores marching down the main highway to the east of the river which was the best road. Alvintzy and his staff would accompany this column.

When brought together where Monte Baldo ended and the plain before Rivoli spread out, so the plan went, these six columns would encircle the French and destroy them.

Setbacks

There had been setbacks, however. The most distressing had been the lingering siege of Mantua. This city, surrounded by a series of lakes and marshes, had thwarted Bonaparte's attempts to reduce it. Bonaparte's patience had been sorely tried during the summer as he saw his laboriously collected siege train dumped ignominiously into the Mincio River at the approach of an Austrian army of relief commanded by General Wurmser. Bonaparte avenged these losses by defeating Wurmser at Castiglione and Bassano. But even Wurmser's subsequent incarceration in Mantua did little to offset the loss of the heavy guns. As a result, Bonaparte had to be content with merely blockading the city, hoping that hunger and disease would eventually force the Austrians to surrender.

Another setback had been the recalcitrance of the Pope. Pius VI, although cowed by the threat of a French invasion in 1796, had never abandoned hope that the Austrians would drive Bonaparte and the hated French Republicans from Italy. He therefore continued a liaison with the Hapsburgs. The coming campaign rekindled his hopes and emboldened him to withhold payment of a huge cash subsidy to the French government.

The French Army of Italy in January of 1796 numbered close to 46,000 men, 4,000 more than the total of Alvintzy's six columns plus those of Provera and Bayalitsch. But Bonaparte would have to leave troops to watch the gathering Papal forces and also at Mantua to keep the Austrians bottled up inside.

Bonaparte had distributed his forces in such a way as to cover the blockade of Mantua and to guard against any threatened invasion from the east over the Piave or from the north down the Adige. From east to west Bonaparte's men were deployed as follows: Rey occupied Salo, Desenzano, and Lonato with 4,200 men. His objective was to cover the western edge of Lake Garda. He was aided by a tiny flotilla that operated on the lake from the ports on its southern shore. Joubert covered the eastern side of the lake and the Adige valley. He had 10,296 men at La Corona on Monte Baldo and at Rivoli. Massena, with 9,300 men, was located at Verona.

Augereau's objective was to cover the Adige from Verona to the Po. He disposed of 10,500 men. He was especially concerned with Legnano. This town had the most important bridge over the Adige after Verona; the loss of Legnano could uncover the blockade of Mantua. Serurier continued the siege with 8,500 men, while Lannes masked the Papal States with 2,800 men who were positioned south of the Po near Bologna.

As long as Wurmser held out in Mantua, Bonaparte could not pursue the Austrians into the Tyrol or Carinthia. Wurmser, meanwhile, showed no signs of surrendering.

More Rivoli

The 200th Anniversary Series on Napoleon in Italy

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. In the winter of 1796-1797, General Bonaparte's campaign in Italy was at a standstill. The two successive attempts by the Austrians to relieve the siege of Mantua had resulted in the battles of Castiglione and Arcola, both Austrian defeats which had added luster to 27-year-old Bonaparte's reputation, but had not resolved the campaign.

In the winter of 1796-1797, General Bonaparte's campaign in Italy was at a standstill. The two successive attempts by the Austrians to relieve the siege of Mantua had resulted in the battles of Castiglione and Arcola, both Austrian defeats which had added luster to 27-year-old Bonaparte's reputation, but had not resolved the campaign.

Alvintzy vs. Bonaparte: Clash of Eras and Styles

Bonaparte Builds a Reputation

Napoleon Bonaparte, 34 years younger than Alvintzy, commanded the French forces in Italy. Starting in April of 1796, Bonaparte had changed French fortunes in the Italian theater by driving the Kingdom of Piedmont from the war and by throwing the Austrians out of northern Italy. He had also won a number of notable victories over four separate armies and had brought almost all of Italy (with the exception of Naples) within the orbit of the French Republic.

Napoleon Bonaparte, 34 years younger than Alvintzy, commanded the French forces in Italy. Starting in April of 1796, Bonaparte had changed French fortunes in the Italian theater by driving the Kingdom of Piedmont from the war and by throwing the Austrians out of northern Italy. He had also won a number of notable victories over four separate armies and had brought almost all of Italy (with the exception of Naples) within the orbit of the French Republic.

Rivoli: Introduction and Situation

Opening Moves Confuse Napoleon

French Success Turns Into Misfortune

French Counterattacks Reverse the Course of Battle

First Installment: Side Road To Immortality

Second installment: The Supporting Cast

Third installment: Maintaining the Initiative

Fourth installment: General Bonaparte Defends His Conquests

Fifth installment: Napoleon Turns Defeat into Victory

Sixth installment: One Final Victory: Rivoli

Seventh installment: Endgame: The Pursuit to Final Victory

Eighth installment: Instrument of Victory: Army of Italy

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #7

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by Emperor's Press.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com