Napoleon Bonaparte was only a local hero in Paris in early 1796, having helped crush the royalist counter-revolution of 5 October with the famous "whiff of grape." Not yet 27 when he assumed command of the Army of Italy in April, this young general would become one of the most well-known field commanders in Europe in less than a year.

Italy was supposed to be a secondary theater of war compared to the main French effort in Germany with armies under Jourdan and Moreau. However, General Bonaparte's first field command witnessed a series of rapid engagements which forced the Sardinia-Piedmontese army under Austrian General Colli out of the First Coalition against Revolutionary France. The Austrian army in northern Italy under General Beaulieu, now fighting without its ally, was then chased into the fortified city of Mantua which Napoleon put under siege.

In July, a new Austrian army of nearly 50,000 men under General Wurmser moved in two columns into northern Italy against Bonaparte's 43,000 French with one of its objectives to relieve the 13,000 troops in Mantua. Napoleon marched immediately against the Hapsburg columns, defeating each in turn and trapping Wurmser and 15,000 more Austrians inside Mantua by mid-September.

Despite defeating three armies in less than six months, General Bonaparte and his thinned ranks had to face a fourth Austrian army under General Alvintzy. This would be the most daunting part of the Italian campaign of 1796-97 as the second Austrian attempt to relieve Mantua would result in the first battlefield defeat for 27-year-old Napoleon. [We use "Napoleon" and "Bonaparte" interchangeably even though he was not known as Napoleon until he became Emperor in 1804.]

The French successes at Castiglione (5 August, 1796) and Bassano (8 August, 1796) trapped the defeated Austrian army of Wurmser -- originally sent with hopes of driving Bonaparte from northern Italy -- in the fortress of Mantua. With this once formidable Austrian force now safely bottled up, General Bonaparte spent the month of October 1796 turning his attention to the numerous political problems that had erupted throughout Italy. These difficulties were mostly a direct result of the rapacious looting that had occurred as the French government and its agents tried to address an unending need for money.

Napoleon played the diplomat to counter the anti-French efforts of the Pope and the British government. He secured a treaty with Genoa, shored up the alliance with the Piedmontese, signed a peace treaty with the Neapolitans, and formed three new republics out of northern Italian territories: the Cisalpine, the Cispadine and the Transpadine. All of these actions served to keep the enemies of the French Republic temporarily under control in Napoleon's rear.

The Austrians, however, were planning to mount another major offensive with the purpose of relieving Mantua and the troops trapped inside. Baron Josef Alvintzy with 46,000 men prepared to descend into northern Italy. Napoleon had less than two thirds that number to face them (not counting Kilmaine's men that were covering Mantua). To make matters worse, many of the ranks were thinned by the various diseases that had been contracted on siege duty in the swampy ground near Mantua. This may have reduced the French effectives to slightly more than 20,000 men.

At right, period lithograph shows Napoleon leading his men over the bridge at Arcola.

At right, period lithograph shows Napoleon leading his men over the bridge at Arcola.

The fact that the Austrian

had once again split their army

no doubt pleased Bonaparte.

The Austrians under Alvintzy came down into northern Italy the same way as Wurmser had before: splitting their forces into a column of 19,000 men under Davidovitch which moved down the Adige valley, while a larger force of nearly 29,000 directly under Alvintzy attacked via the Sacile-Bassano route. One motive for splitting their force was the inability of the Austrian supply system to support a large army using a single line of supply. Another was the hope of encircling an unsuspecting enemy or forcing Napoleon to divide his own forces to respond to each column.

The fact that the Austrians had once again split their army no doubt pleased Bonaparte. Based on faulty intelligence which made Napoleon think Davidovitch's force was much smaller than it actually was, he ordered Vaubois' division to attack Davidovitch. It was his plan to drive this column back into the Tyrol then take most of Vaubois' men and reunite them with his main army to deal with Alvintzy. The problem was that Vaubois was taking on more than he could handle. On 2 November he launched an attack against the Austrian position near Neumarkt. Davidovitch allowed the French to spend themselves against his position before counterattacking and putting the vastly outnumbered French to rout.

By the 3rd Trent had been lost and as the Austrians pressed on, the shaken Republican troops were driven out of successive positions until they stopped at Rivoli (the last defensive position before Verona) on 7 November.

While this disaster was occurring, Alvintzy advanced with the main Hapsburg army. Massena abandoned Bassano and fell back from the Brenta River position. When informed of this move, Bonaparte angrily demanded that the position be retaken. Augereau's division as well as Massena's launched a counterattack on 6 November.

Outnumbered, the French fought well and had several successes, but Augereau's men, unable to retake Bassano, eventually fell back.

The French became increasingly demoralized as they retired into the defenses of Verona. Joubert's division, the last reserve, was sent to Rivoli to try and stabilize the situation. The French watched while the Austrians arrived outside Verona on 8 November to reorganize for an attack. Early on the 10th, a brigade under Hohenzollern attacked the French outer works and was repulsed. Convinced that he would have to establish a formal siege and would require his bridging equipment that had yet to come up, Alvintzy pulled back three miles to a defensive position around the town of Caldiero.

Napoleon reasoned that this was his chance to seize the initiative and emptied the hospitals of walking wounded in an effort to lessen the odds against him. He decided on a dawn attack for 12 November. The men moved out of their Verona cantonments at midnight. At dawn the first attack was launched. The French came on through a swirling snow storm.

At right, the bridge at Arcola as it stands today.

At right, the bridge at Arcola as it stands today.

Because of the muddy ground,

artillery was almost impossible to move

and the French attack outran

their artillery support.

The Austrian right was anchored on a ridge line covered with vines. The town of Illasi was the strong point of this position. Massena's men charged the position and took it at the point of the bayonet. Massena then swung to the right and south and assaulted the center of the Austrian position around the town of Colognolo.

Augereau was attacking in the plain and turning the Austrian left at the town of Caldiero. As his men swept forward they linked with Massena and drove the Hapsburgs out of Colognolo. The Austrians fell back covered by their guns. Because of the muddy ground, artillery was almost impossible to move and the French attack outran their artillery support. It was now past noon and the battle was about to turn. Fresh Austrian troops under Provera had marched to the battlefield and were sent in against the weary French. At first they were slowed by the morning's victors, but as the entire column was deployed and came on the weight of numbers finally caused the French to give way. Although some units fled, most of the French withdrawal was deliberate. The mud, which had worked against the French all morning, now worked for them as the Austrians were unable to launch an effective pursuit.

Napoleon had suffered his first defeat in a pitched battle. Casualties had been about equal but the larger Austrian army could afford the losses. The real blow was to French morale. Even Napoleon felt that all might be lost. "Perhaps the hour of the brave Augereau, of the intrepid Massena, of Berthier, or my own, is ready to strike. Then, what would become of these brave men? We are abandoned in the depths of Italy." He wrote to Josephine in Milan and told her to leave and go to Genoa. She ignored this advice and put on the show of confidence which may well have prevented an anti-French uprising.

The days of 13 and 14 November passed as Alvintzy readied his army for an assault on Verona. Ladders were prepared and the bridging equipment had at last come up which would allow for a linking of the two Austrian columns. The campaign of 1796 had reached another dire crisis for the French. It was at this junction that Napoleon Bonaparte produced one of his most daring plans.

He would leave a skeleton force in Verona, and march the remainder of his army to the southeast down the right bank of the Adige River. He would then attempt to cross to the north side of the river and move against the rear of Alvintzy's column. Hence on the night of 14 November the French divisions marched to the town of Ronco and began to bridge the river.

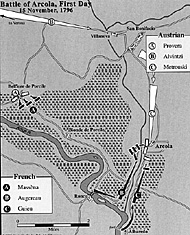

On the morning of the 15th the French divisions crossed the Adige and marched on the town of Arcola. From there they planned to move on Villanova and seize the position in the Austrian rear while Massena made a parallel advance. The ground would create the first problem for Napoleon. With the exception of a dike road which ran along the Alpone River, all the remaining area was swampy and virtually impassable after the rains of the previous month. Therefore it was along this road that Augereau's men advanced. They were surprised to find the town occupied by 2,000 Croat infantry in a walled farm yard which overlooked the only crossing at a bridge. An immediate assault was launched and summarily beaten back.

General Robert, the commander of the lead brigade, led his men in a headlong rush over the bridge. This too failed as Robert fell dead in the assault. Time was of the essence, for if the Austrians were able to send reinforcements, the entire plan was in jeopardy. Lannes led his brigade forward but despite the sight of the previously wounded and yet unhealed general taking the lead the withering fire drove back the French.

First Day of Arcola--Larger map.

First Day of Arcola--Larger map.

Bonaparte was knocked

into a canal which paralleled

the Alpone and he nearly drowned.

Desperation now gripped Napoleon and he seized a standard and attempted to lead a charge. Crying that they would be lost without him several grenadiers tried to interpose themselves between their commander and the deadly fire. The result was that Bonaparte was knocked into a canal which paralleled the Alpone and he nearly drowned before being rescued.

Augereau had had enough and called for a retreat. Ironically, within the hour a small French brigade under General Guieu would surprise the Croats by crossing the Alpone downstream and seizing the town. But as darkness fell, they too retreated as they couldn't find any French support in the area.

The day had certainly not gone as planned. In fact, the already unsteady French morale must have been once more shaken. The only gains of the day had been by Massena's men when they seized the town of Porcile, which protected the northwest approach to the bridgehead at Ronco.

What Napoleon could not have known but might have suspected was that the Hapsburgs were themselves in a state of confusion. What were the French doing attacking? Had they received reinforcements whose approach had gone undetected?

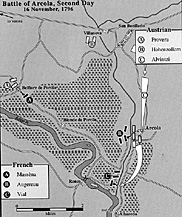

The Austrians opened the attack the next morning by driving Massena's men out of Porcile. The French gave ground slowly as they retreated toward Ronco. Bringing up reserves, Massena had his cavalry maneuver against the Austrian's left flank. On the right, Augereau would find the fight of the second day similar to the first, with the blue coats still unable to storm the bridge.

Throughout the day numerous efforts were made to bridge the Alpone without success. The normally shallow river had become a torrent as a result of the rainy weather. The day ended with the enemy's positions much as they had started the day.

Despite the various setbacks of the two previous days, Napoleon believed that the French morale was on the rise and that of his opponent on the wane. Incredible as this may seem, Napoleon grasped things from his limited perspective on the field that are difficult to perceive or understand even with hindsight.

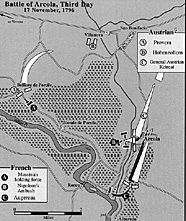

In the drizzly gloom of that November morning the French were once more surprised to find the Austrians on the move as they opened a stronger version of the previous day's attack on Porcile and toward Ronco. This time the strength of numbers pushed back Massena's men and soon the bridgehead was threatened. This had been anticipated by Napoleon. The majority of the French army's cannon were waiting for the Austrian rush for the bridge. These guns delivered deadly canister into the massed target. In a moment the Austrian morale collapsed and the fleeing troops were ridden down as the French cavalry reserve was unleashed.

With his left flank secure, Bonaparte was able to concentrate his efforts on Arcola and the eastern bank of the Alpone. Two divisions crossed at a bridge which had at last been constructed. At the same time a brigade of men moved up the western bank and prepared to assault Arcola.

After three days the French threat finally materialized and Alvintzy, who had thrown his best punch against the French left, now had to commit his final reserve to stop Bonaparte's two divisions which were moving north against Arcola. The two lines collided about one mile south of town and what developed was a horrific firefight.

In the meantime Arcola had fallen. After three days of almost continuous assaults, the town was taken by deception. After advancing against the town once more, the French appeared to retreat. The Croats, along with other Austrian troops, sensing that the moment of victory had finally arrived, rushed out and fell upon the retreating Frenchmen. They poured across the bridge and against the rear of the retreating troops only to suddenly see them turn in place and deliver a volley. Moments later another French unit charged out of a hidden position into their rear. After three days of unmerciful fire, the Revolutionaries gave no quarter. Few of the Croats escaped the trap. The town of Arcola was finally in French hands to stay.

To the south, the Austrians were still grimly holding on. Their commander Alvintzy, however, had given up hope of winning and was hoping merely for a stalemate. Around 3 p.m., Napoleon dispatched a group of his personal guides (the forerunners of the chasseurs ˆ cheval of the Imperial Guard) to ride around to the rear of the Austrian line blowing trumpets and waving flags. Thinking that they were attacked by a much larger force, the tired Austrian advance guard fell back on their main body, which, in turn, was pushed back when Vial's 800 men from Legnano appeared on Augereau's right flank, turning the Austrian left.

Napoleon had again demonstrated his uncanny ability to take stock of his enemy's morale, and he successfully wagered that one more blow, however illusory, would be enough to tip the scales of this battle to his favor.

Alvintzy's army retreated via Sacile and a few days later Davidovitch's column followed suit. The most dangerous phase of the 1796-97 campaign was over for General Bonaparte, but it would require the defeat of one final Hapsburg army for the French to finally capture Mantua and secure Italy.

Of his most recent victory, Napoleon said in a letter to Carnot that: "Never yet has a battlefield been so hotly disputed as that of Arcola."

The 200th Anniversary Series on Napoleon in Italy

About the author:

Todd Fisher is the CEO of Emperor's Press which publishes Napoleon magazine. He is also the Executive Director of the Napoleonic Alliance. This is the fifth installment of an ongoing series begun in issue #2 promoting the Napoleonic Era's bicentennial.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Second Day of Arcola--Larger map.

Second Day of Arcola--Larger map.

Third Day of Arcola--Larger map.

Third Day of Arcola--Larger map.

First Installment: Side Road To Immortality

Second installment: The Supporting Cast

Third installment: Maintaining the Initiative

Fourth installment: General Bonaparte Defends His Conquests

Fifth installment: Napoleon Turns Defeat into Victory

Sixth installment: One Final Victory: Rivoli

Seventh installment: Endgame: The Pursuit to Final Victory

Eighth installment: Instrument of Victory: Army of Italy

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #6

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1996 by Emperor's Press.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com