The Americans and Japanese near Afua doggedly regrouped on 20 July. Miyake Force's battered regiments, now reduced to company strength, finally received reinforcements when the 79th Regiment, 700 strong, along with a sixty-man mountain artillery company possessing a single gun, joined forces with General Miyake south of Afua. Additional men and supplies were also on their way.

On 19 July, General Adachi, at 18th Army Headquarters, originally had ordered the 66th Infantry to attack near Kawanakajima in order to cover the north flank of the 20th Division. When he

learned the actual extent of the 20th Division's losses, he canceled the attack order for the 66th Regiment and instead employed those troops as bearers to haul supplies to General Miyake's desperate troopS.

[68]

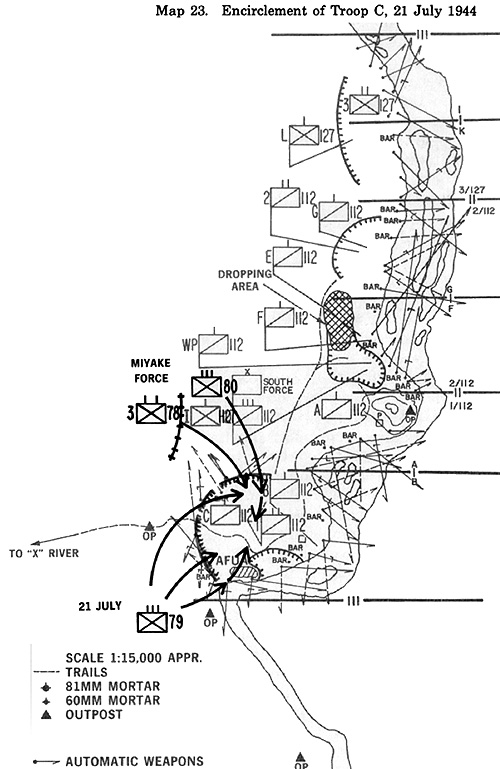

Miyake meantime coordinated his attack plans with Lieutenant General Nakai, who had moved 20th Division headquarters forward together with the 79th Infantry. At the same time, General Cunningham and the 112th Cavalry prepared their defenses to stop another Japanese thrust. He switched the battered Troop A from its ostensibly "reserve" position and substituted Troop C on the drawn-up right flank. Troop C occupied a place the Japanese called Tsuru. The entire 79th Infantry would attack Tsuru at 1600 that day.

Forty-five minutes after the scheduled H-Hour, the 79th Infantry's lone

mountain gun barked as the first of the eight rounds it would fire smashed into Troop C's perimeter (see map 23). The Japanese had manhandled the gun in pieces through the foliage to within 300 meters of the American defenses. One 112th Cavalry veteran remembered his fear as he listened to the Japanese out in the jungle setting up the gun and hammering aiming stakes into the ground. The Japanese fired at point-blank range,

aiming at the distinctive headquarters tent. One shell explosion wiped out all tactical command by wounding the commanding officer, ist Squadron, the commander, Troop C, and an artillery liaison officer. Even before their mountain gun stopped firing, Japanese infantrymen were closing on Troop C.

Any firefight is initially a confused melee, but this one was especially so. Just before the Japanese attack, an American observation plane circling overhead dropped a message to Troop C that U.S. troops were in front of C's lines. That mistake permitted the Japanese infantrymen to walk into Troop C's perimeter. The cavalrymen were reluctant to fire, not wanting to kill fellow Americans. The pilot's error was excusable, because to compound the chaos, many Japanese soldiers wore American ponchos

draped over their shoulders as well as other items of American equipment. The Americans themselves were dirty and grimy after more than three weeks on the line, making it impossible to distinguish friend from foe more than a few yards away. It was literally face-to-face combat. One Troop C NCO said, "Unless you looked them in the face you didn't know whether they were enemy or not." A Japanese infantryman walked right up to this same American sergeant, who shot at him and missed. The Japanese soldier then dived into the high, above-ground roots of a mangrove tree, and an American machine gunner loosed a short burst of fire that killed him. [69]

The 79th Infantry apparently assumed that Afua had already been secured, for the Japanese just walked right into Troop C's defenses without firing. Neither group did anything to alarm the other. Both sides had the impression that they were meeting friends. Once heavy firing broke that spell, the Japanese spread out, fanlike, and encircled Troop C. The Japanese attack struck from the south to force its way between Troops C and B. They had initial success, driving back Troop C, mainly because of American communication difficulties that had caused a forty-five-minute delay in delivery of preregistered artillery fire. Once the artillery began to explode and the cavalrymen recovered from their surprise, the men of the 79th Infantry, who had wedged themselves into the U.S. defenses, found themselves, in turn, surrounded by the Americans. Shortly afterward, the remnants of General Miyake's forces attacked Troop C from the west and again isolated the Americans from their regiment.

Maj. Takada Sajuro, a 20th Division staff officer, was just then trying to contact Miyake's forces, whose headquarters were in deep jungle. Even there, enemy shells were screaming overhead or exploding randomly. Everything was in disarray. Takada searched for the 78th Infantry commander,

whom he found wounded and sitting cross-legged under a tree, clutching the regimental colors. Takada could hear gunfire reports all around, but because of the jungle veil could not tell its precise direction. His overriding feeling was that everything was messed up.

He thought in sorrow of the troops who had to watch helplessly while the enemy flew in transport aircraft to airdrop supplies, while Japanese had only rainwater to drink. His reverie was broken when several wounded Japanese infantrymen stumbled or were carried past him into the regimental headquarters. Takada felt the agony the frontline commanders were going through because they had been ordered to accomplish a mission that was beyond their means. [70]

Whatever those officers privately thought, they led their troops with fanatical courage. The American artillery bombardment finally broke up the Japanese attackers, who took refuge in small groups scattered along the fringes of the jungle. The Japanese attack to roll up the 112th's south flank had failed, but it had managed to surround Troop C.

Troop C suffered fifteen casualties, including at least two dead. Early in the fighting, a few of the wounded from the Troop C sector managed to make their way back to the squadron headquarters, where they reported that two platoons of Company I, 127th Infantry, also had been pushed into Troop C's perimeter by Japanese troops attacking from the north. The wounded men also stated that they believed enemy casualties were very high, mainly because of the effectiveness of friendly artillery fire.

That observed fire, though, lasted only until about 1900, when Japanese soldiers cut the 112th's communications lines, after which the artillerymen had to resort to blind interdictory fire throughout the night. The Japanese used the cover of darkness to probe Troop C's defenses, mainly by fire with small arms and automatic weapons fire, and an occasional mortar round. Both sides had probably spent themselves, but neither would acknowledge it. The fighting continued spasmodically throughout the night as Japanese infantrymen sneaking close to the cavalrymen's perimeter would shoot at anyone careless enough to show himself in the moonlight.

The troopers of C and infantrymen of Company I resorted to a circle perimeter about 150 meters wide, where about one hundred Americans faced perhaps four or five times that number of Japanese. About 275 meters separated them from their 1st Squadron, but in the isolation of the jungle thicket, it could well have been 275 kilometers. Troop C was cut off and alone. Their Japanese tormentors, however, were

also disorganized during their attack and subsequent night fighting. They, too, had to reassemble in intermittent rainshowers and deadly American artillery. So the Japanese laid ambushes on the trails leading to Afua and sent squad-size units crawling forward to

test the American defenders' resolve.

At the 112th Cavalry command post, preparations to break the Japanese siege and to rescue Troop C were already underway. Troop B had started to move from Afua the previous night, but the combination of darkness and Japanese infantrymen from the 79th Infantry along the trail barred the Americans' way. Early on the morning of 22 July several American patrols from the 112th and 127th Infantry tried to reestablish contact with Troop C. Each in turn hit a Japanese ambush and fell back, unable to locate precisely Troop C. Gunfire reports to the south added to the uncertainty, for no one knew if it came from Troop C, from American patrols trying to reach C, or from a 112th patrol operating in the area. A spotter aircraft pilot reported only Japanese soldiers at the suspected location, because when the plane flew over, the men on the ground all ran for cover. To attack unprepared was better than to wait for all possible information, which might arrive too

late to prevent the destruction of Troop C. So around 1300, Troop E began its attack

with about sixty men (see map 24).

Troop E passed through Troop B's sector and then moved southwest into the jungle. Suddenly prolonged bursts of small arms fire hit Troop E from the front and

flanks. Without warning, a booby-trapped American bomb exploded in Troop E's midst

as the men scurried for safety. When the dust settled after the explosion, one cavalryman

was dead, the three others maimed. Still under enemy fire and suffering losses, the troop

commander received permission from headquarters to withdraw. The men were badly

shaken, and General Cunningham sent them to the vicinity of the dropping ground, a

relatively quiet sector just then, to regroup.

Elsewhere a similar story trickled back to headquarters. A wire party of twelve

men managed to reach to within 300 meters of suspected Troop C positions, where a

Japanese trail block prevented any further advance. Two Americans fell wounded, and both sides escalated the fight. First, about twenty men of Company I went to reinforce the ambushed communications party in hopes of pushing through to Troop C. They deployed a firing line, attacked the Japanese, pushed them back perhaps one hundred meters, but then encountered Japanese reinforcements. Thinking an imminent

breakthrough to Troop C was possible if just a bit more pressure were applied, General Cunningham sent a captain and three enlisted troops from Headquarters Troop and a

lieutenant with twenty men from the mortar platoon to lend support. These cavalrymen, however, stumbled into a Japanese ambush before reaching the advance party. Japanese

automatic weapons operators and riflemen shot down both American officers in the first seconds of the fight. That was enough for the rest of the patrol, which returned to

headquarters carrying their wounded officers with them. They claimed to have killed four Japanese in the short, bitter firefight. Lacking reinforcements, fighting against

determined Japanese resistance, and with night approaching, the advance wire party and Company I men also pulled back to protect the rear of General Cunningham's command post for the night. It had been a frustrating day for the Americans.

It was even more so within the small Troop C perimeter, because the

cavalrymen could do little to help themselves. Japanese snipers had climbed nearby trees and fired down at anything that moved. Anyone standing up was a potential target, and the tension was enormous. Any movement was dangerous because Japanese infantrymen less than fifty meters away could fire into the tightly packed perimeter. Furthermore, a slough filled with old logs and other debris from previous flash floods ran into the perimeter. This slough provided the Japanese excellent cover to crawl closer and closer to Troop C's lines. All the cavalrymen could do was fight back, tend their wounded, and, under cover of darkness, bury their five dead.

According to veterans of that fight, they really did not expect any relief. They

understood that the regiment might be simultaneously fighting for its life and that their

situation, though desperate, was not unique. Beyond that, they could depend on one

another. "You knew the guy that had been back there. You trusted him. You knew if

you needed him he was there." That confidence, buoyed by the fight for self-preservation, and an infantryman's fatalism expressed as "You lived from day to day and accepted it as a way of life,' gave them the will to resist and endure. Similar emotions probably provided the same impetus to Japanese soldiers. So Troop C fought on alone against the Japanese, completely out of contact with other American units, yet only a few hundred meters away.

[71]

Following the failure of the first day's efforts to rescue Troop C, the

commanding officer of the 127th 'Infantry and assistant operations officer (G-3), 32d Division, arrived at the 112th's command post at 1800 for a council of war with General Cunningham. Their original plan called for the 127th Infantry to rescue Troop C and to

relieve the 112th Cavalry. The 112th would then establish positions along the Afua-Palauru track, halfway between the Driniumor and River X, to cover the area south to the Torricelli Range and to act as a general reserve for the covering force. These orders

were never executed, for between the time the orders were written and the time they were passed, the battlefield situation had changed. It seemed clear that the major Japanese attack was directed against the heart of the 112th's defense around Afua. The 112th could not be relieved unless General Hall chose to abandon his entire south flank.

Since there had been no contact with Troop C for the past two days, no one was certain that it still existed. Even if the men were alive, no one knew exactly where they were. On the morning of 23 July, a pilot erroneously reported "a large group of Americans" 700 meters southwest of Afua. All that the combat patrols found was a Japanese machine gun nest, which they destroyed. Shortly after noon, the same pilot made amends by discovering Troop C's location. He was sure this time because some of the men were without shirts and he could easily recognize their white skin in the clearing. The Americans also detonated a white phosphorus grenade and waved a white flag to signal the airmen that they were still alive. Now that

they had been located, they had to be rescued.

Chapter 7: Attrition

Chapter 7: Directives

Chapter 7: Miyake Force

Chapter 7: Regrouping

Chapter 7: Rescue of Troop C

Chapter 7: US Redeployment

Chapter 7: Japanese Flank Attack

Chapter 7: Japanese Change of Plan

Chapter 7: Aftermath

Back to Table of Contents -- Leavenworth Papers # 9

Back to Leavenworth Papers List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com