The 41st Division, it will be recalled, had meticulously planned an attack against American defenses to the north, near Kawanakajima. At the last moment, General Adachi had diverted the division from its scheduled attack in order to reinforce the 20th Division and press home its assaults against Afua. This decision had two important repercussions. First, the 41st Division staff officers had no time to devise an appropriate

plan of attack against the American defenses. All their time was consumed moving their men through the jungle to their new assembly areas.

The 41st Division, it will be recalled, had meticulously planned an attack against American defenses to the north, near Kawanakajima. At the last moment, General Adachi had diverted the division from its scheduled attack in order to reinforce the 20th Division and press home its assaults against Afua. This decision had two important repercussions. First, the 41st Division staff officers had no time to devise an appropriate

plan of attack against the American defenses. All their time was consumed moving their men through the jungle to their new assembly areas.

Nevertheless, the Japanese dismissed the Americans defending Afua as inferior to those near Kawanakajima, where the 41st Division had been in combat. Against these "inferior troops," a frontal attack conducted on a narrow frontage with forces echeloned in depth appeared to offer the Japanese the best possibility of achieving the breakthrough General Adachi had ordered.

The second problem also originated in the cancellation of the 41st Division's originally scheduled attack. Officers in the 41st Division opposed the decision and complained openly that the 20th Division's lack of courage had caused the Aftia stalemate. Word of their dissatisfaction reached General Adachi, who reprimanded the division commander, Lieutenant General Mano. This rebuke infuriated the regimental and battalion commanders, who decided among themselves to regain their commander's honor by overwhelming the American defenses regardless of losses. [93]

The 2d Battalion, 239th Infantry, crossed the Driniumor on 2 August and

proceeded along the bank adjacent to the 238th Infantry. Shortly after dark, both units charged out of the jungle against the Ist Squadron's positions. The 41st Artillery Regiment and mortar fire supported the Japanese thrust, but the bunched-up infantrymen simply dissolved under the impact of the concentrated U.S. firepower. Japanese officers regrouped their men under fire and charged forward, determined to prove that the slight against their division had been unjustified. They died in bunches, as heaps of bodies fell in front of the cavalrymen's perimeter. Only darkness saved the Japanese from complete extermination.

The 1st Squadron suffered only four men slightly wounded. Nearly 100

Japanese were' killed. All night, screams and moans resounded outside the cavalrymen's perimeter. In the early light of 3 August the

Americans could see stacks of Japanese corpses marking the axis of attack.

Although the 112th Cavalry enjoyed overwhelming materiel and firepower

superiority, the protracted warfare of attrition had ground down the troops, who were now in poor physical shape. Sickness skyrocketed. The Americans detected that they were winning the struggle, but they had no idea how many more of their friends would be killed or wounded in the savage fighting. They were worn out, tired, sick, and understrength. But they could still improve their defensive positions. Registration of

mortar and artillery concentrations boomed during the day as the 112th Cavalry surrounded their perimeter with a band of fire, ready on call. Amidst these major preparations, there was no respite from small-scale patrolling, with its usual deadly results.

A Troop G patrol operating east of the Driniumor walked into a Japanese

ambush, and its sergeant was killed by machine gun fire. The other Americans quickly ran from the site and then called in mortar fire. Another patrol, later in the day, could find no evidence that the skirmish had ever taken place. A six-man patrol vanished a little more than a football field's length from the 112th's perimeter. The men were on a three-day reconnaissance patrol when they stumbled into a Japanese ambush, probably set by stragglers of Miyake Force still trapped behind the U.S. lines. A patrol from Troop G sent to their rescue was, in turn, apparently ambushed and lost two men killed and six wounded.*

Another chilling possibility is that the G troopers reached the ambushed

American patrol only to be shot by their comrades. A trooper recalled that he heard someone yell "Watch out!" just before Thompson submachine gun fire raked the men. On the afternoon of 1 August, the first inkling of the Ted Force envelopment reached General Adachi, when he received reports of enemy landings near Yakamul. That same afternoon, the 237th Infantry arrived in the Afua area. In conjunction with

survivors of the 238th and the 239th Infantry, the 237th set out to attack across the Driniumor at 0200 on 3 August. Poor coordination and late arrival of troops caused a postponement.

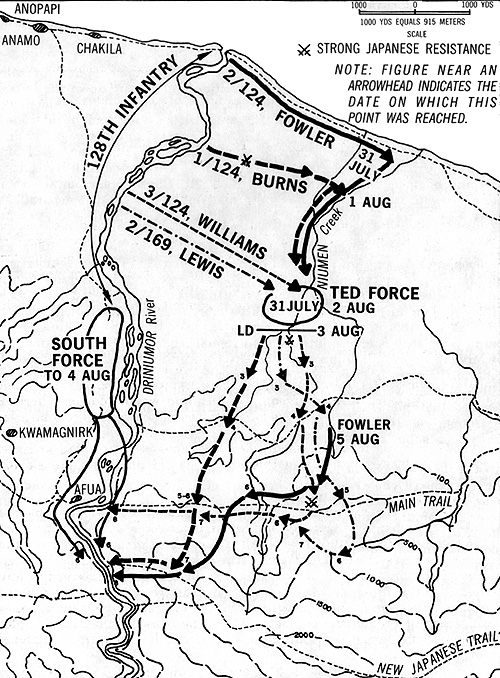

Also on 3 August, General Adachi ordered the Aitape offensive to end at noon 4 August. Attacks then in progress would continue in order to cover the Japanese withdrawal. Shortly thereafter, Adachi heard that about 400 Americans, probably the 3d Battalion, 127th Infantry, had crossed the Driniumor in the vicinity of Kawanakajima

and were rapidly advancing east (see map 31). Adachi ordered elements of the 237th Infantry to check this American advance.

Elsewhere elements of the 41st Division prepared for what would be their final attack against the 112th Cavalry. [94]

Morale was low among the Japanese troops, who had only one day's rations leftand were short of medical supplies. Their condition had deteriorated to such an extent that the physically fit soldiers took the clothes and rations from the weaker men. [95]

Platoon Sgt. Claude Rigsby of Troop B was on the firing line that morning. His troop, part of Lieutenant Colonel Grant's lazy-S line, formed a pocket facing towards the jungle. Rigsby could see very few Japanese because of the thick jungle, and the fleeting figures he could see attacked in open formations. They advanced into the pocket, where U.S. automatic weapons and 60-mm mortars tore them to pieces. Artillery blasted the Japanese remaining in the jungle. The fighting raged as the Japanese tried desperately to break the American lines. A few Japanese actually reached the American outpost line and drove the defenders back. But after two hours, more than 185 Japanese

were dead or dying. The squadron commander watched impassively as sixteen wounded Japanese committed suicide in front of his defenses. [96]

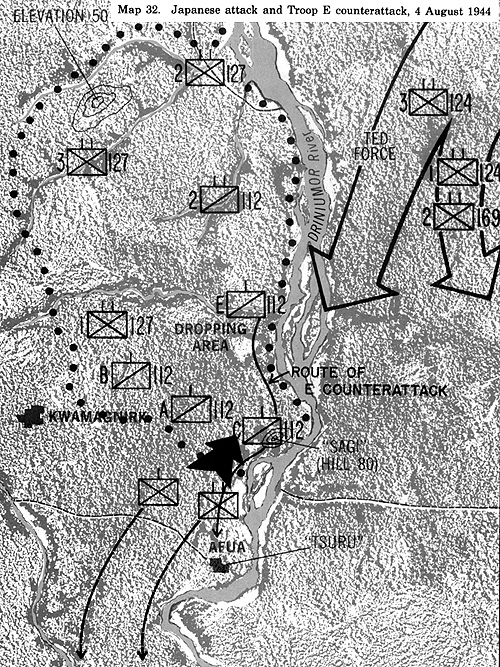

As soon as the Japanese attack had begun, General Cunningham alerted Troop E for a counterattack, and at 0900, Troop E deployed to mop up any remaining Japanese and reestablish the cavalrymen's outpost line (see map 32). As they passed through Troop C's lines and walked crouched forward toward the jungle, three Japanese riflemen hiding under the roots of a tree on which an American officer was standing shot and killed Lieutenant Christensen. Enraged cavalrymen killed the Japanese with hand grenades. Six other Japanese died during this sweep, as did another 112th Cavalry lieutenant.

The human carnage along and in the Driniumor was appalling. A member of the 112th's Supply Company arrived at the river around this time and at first glance thought that it was full of logs. Another look registered that Japanese corpses choked the river. [97]

If ever during a battle morale soared and exhilaration appeared, it was then, for the cavalrymen seemed to have sensed that the Japanese were finished. So badly were the Japanese beaten that nine surrendered. These prisoners were put to work burying the Japanese dead scattered around the perimeter. While the worst of the 112th's ordeal had passed, the danger permeating the lives of frontline troops had remained.

Chapter 7: Attrition

*As for the lost patrol, a wounded member was found by the 127th Infantry, and another made his way to the 112th command post. Subsequent patrols found a third wounded cavalryman who had been in the bush three days. He believed his lieutenant and one other enlisted man had been

killed. Those bodies were never found.

The Japanese had crossed the Driniumor upstream and then swung north to

strike the American positions from the jungle and along the west bank of the dry riverbed. Their attack began at 0615 on 4 August.*

The Japanese had crossed the Driniumor upstream and then swung north to

strike the American positions from the jungle and along the west bank of the dry riverbed. Their attack began at 0615 on 4 August.*

*No Japanese record of this attack exists.

Chapter 7: Directives

Chapter 7: Miyake Force

Chapter 7: Regrouping

Chapter 7: Rescue of Troop C

Chapter 7: US Redeployment

Chapter 7: Japanese Flank Attack

Chapter 7: Japanese Change of Plan

Chapter 7: Aftermath

Back to Table of Contents -- Leavenworth Papers # 9

Back to Leavenworth Papers List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com