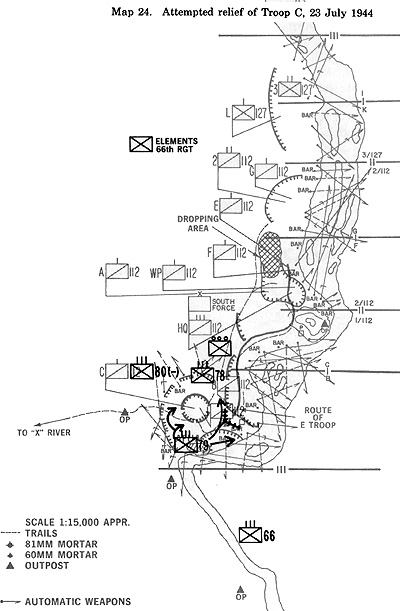

The rescue attack started at 1600. The two-pronged American attack had

Troops A and B, with a platoon of Troop E in support, attacking to the east, while the 2d Battalion, 127th Infantry, attacked from the west. About an hour later, the cavalrymen had reached about 185 meters from Troop C, but were meeting increased Japanese resistance.

The rescue attack started at 1600. The two-pronged American attack had

Troops A and B, with a platoon of Troop E in support, attacking to the east, while the 2d Battalion, 127th Infantry, attacked from the west. About an hour later, the cavalrymen had reached about 185 meters from Troop C, but were meeting increased Japanese resistance.

The two advance American platoons deployed and built a firing line. Orders were for Lieutenant Boyce and his platoon to attack the Japanese left flank. They attacked, but could gain only a few meters before heavy Japanese small arms and mortar fire forced the men to crawl to cover. Boyce saw a slough that seemed to offer an avenue of approach against the enemy position. He led his squad into it in column formation. Japanese soldiers defending the shallow depression heaved several hand grenades from above onto the advancing Americans. One grenade landed between the lieutenant and his men. Boyce threw himself on the grenade and smothered the blast with his own body.*

- *His actions earned Lieutenant Boyce a posthumously awarded Medal of Honor.

That heroic action ended the 112th's attack for the day. A corporal threw a smoke grenade to mark the area for 60-mm mortar fire to cover their withdrawal. They had lost, besides Boyce, one NCO killed and six wounded. The 2d Battalion's attack also had pushed westward, and they were fighting for control of a ridge just west of and overlooking Troop C's positions. As both American units were advancing toward each other, the 112th troops were ordered to withdraw to Afua to preclude the distinct possibility of mistakenly firing on each other. The day's fighting had partially lifted the siege by rooting out Japanese of the 79th Infantry from their roadblocks, thus allowing 2d Battalion to reach Troop C's perimeter just before darkness.

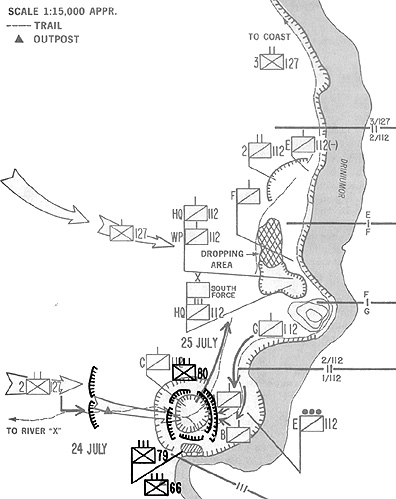

Although the Japanese trail blocks had been broken, small bands of Japanese soldiers continued to fight near Troop C's positions. Even with the added strength of the 2d Battalion, the Japanese refused to release their grip on Troop C. That afternoon, for instance, Troop C tried to break out, carrying its litter cases, but Japanese small arms fire drove the men back. Nevertheless, the cumulative effects of a prolonged battle of attrition were grinding down the Japanese defenders, and Troop C would be able to reach the 112th Headquarters command post by 1000 on 25 July.

Instead of the expected mopping up exercise, bitter fighting characterized the day. Cavalrymen fought brief skirmishes with Japanese patrols, probably the screens for 20th Division Headquarters, then moving south of Afua. The day's fighting left commanders on both sides dissatisfied.

Major General Gill, Persecution Covering Force commander, expressed to

General Cunningham his "inability to understand slowness in the clearing situation." [72]

Gill believed that the 112th was fighting only the Japanese 78th Infantry, but General

Cunningham insisted that at least two Japanese regiments, the 78th and 80th, were

pressing his troops. Both men were wrong, but they could not know it. The entire 20th

Division had arrayed itself against Afua, and according to Japanese sources, by midnight

of 25 July at least 2,000 Japanese were to the right (south) and rear (west) of South Force. [73]

General Adachi at Headquarters, 41st Division, learned that the Americans were continuing to strengthen their Driniumor defenses, that the 20th Division's attack against

Afua apparently had not gone well, and that the 41st Division was preparing its assault near Kawanakajima for 27 JUly. [74]

Morale, he found, was excellent in the 41st Division-junior officers were encouraging each other as they were briefed on the plan of attack. Then the division commander, Lt. Gen. Mano Goro, summoned the small unit leaders to assemble before him. He abruptly announced to his collected officers that the 27 July attack had been canceled and that the division instead would move immediately to Afua. Nothing more was said as the general

walked out. After ten days of planning for the 27 July operation, the subalterns wondered aloud why the attack suddenly had been canceled. A persistent speculation was that the 20th Division had lost the "guts" to cross the Driniumor and that the 41st Division was being sent to Afua to do its dirty work. [75]

The officers of the 41st Division dismissed the enemy at Afua as decidedly inferior

to the Americans they had been fighting near Kawanakajima and so convinced

themselves that a frontal attack, brutally delivered, would smash the U.S. units near

Afua once and for all. Such contempt for, and underestimation of, their enemies at Afua

ultimately would destroy the 41st Division.

Despite the emotional outbursts by 41st Division officers, General Adachi had

ordered General Mano to cancel the attack for several reasons. First, the 20th Division

was nearly worn out from continual jungle combat, and Adachi realized the Japanese

could not turn the Americans' flank without reinforcements. Second, even the strongest

Japanese unit, the 237th Infantry, 41st Division, was unable to crack the strong American defenses near Kawanakajima. The solution was to combine the 41st and 20th divisions for a concerted attack on Afua. This concentration of Japanese forces would thereby improve chances of defeating the Americans in detail. Once again Japanese troops swung south towards Afua, though this time they approached on the Driniumor's east bank.

For the cavalrymen around Afua, 25 July just brought more heavy showers. The rain had begun about dusk the previous evening and had poured uninterrupted throughout the night. Soaked and shivering, the men huddled in their holes until the first gray light. They ate in the pouring rain. Patrols departed, but soon reported back that high water in previously near-dry streams made crossing impossible. About mid-morning the storm passed, and the sun appeared as if to greet the men of Troop C, who were just then making their way into the regimental command post area. There was little time for congratulations, because the fighting in the steamy jungle mist near Afua continued on and off throughout the day.

General Cunningham ordered his troopers to push south and west to dislodge Japanese infantrymen who he assumed were holding the high ground southwest of Afua. General Adachi ordered his infantrymen to attack north and west to wrest Afua from the Americans and to seize Hill 56. Thus the 112th Cavalry and the 79th Infantry both believed that they were attacking the other's defensive positions. In fact, they were

attacking the same ridgeline. The close vegetation, deep jungle, and broken terrain limited visibility, so neither side knew the other's precise location until someone blundered into an opposing

unit. A typical example of a firefight characteristic of the next three days might be as follows:

Occasionally a single determined soldier could hold up ten or even one hundred men, as was the case during the 112th's 25 July drive against a nameless ridge. There a lone Japanese machine gunner blocked the advance of the center of the 112th's line. The cavalrymen had to deploy and work around the solitary gunner, thus precluding the use of friendly artillery to blast the hill. [76]

It was hard, slow, nerve-wracking combat, not at all glamorous, but exceedingly deadly, as fire was often exchanged at ranges of five meters or less. Robert Ross Smith described the nature of the fighting:

Each side complained that the other held isolated strong points, none of which appeared to be key positions. Both sides employed inaccurate maps, and both had a great deal of difficulty obtaining effective reconnaissance. In the jungled, broken terrain near Afua, operations frequently took a vague form, a sort of shadow boxing in which physical contact of the opposing sides was oft times accidental. [77]

If such horrible circumstances may be described as "routine," then 25 July was routine for the cavalrymen until 1800, when two American 155mm rounds exploded in Troops A and B's command post area. Excited, hurried calls from the forward observer stopped the artillery shooting, but five more Americans lay wounded, victims of an accident. Likewise, a few hours earlier another unlucky cavalryman thrashing around in

the bush was mistakenly shot by his own men.

As an aid man tended to his gunshot wounds, a Japanese soldier appeared from the bush to hurl a hand grenade at the medic. The grenade did not detonate, and the enraged aid man turned on the Japanese and killed him. Both American and Japanese soldiers were, in a sense, the victims of bad luck.

Most of the 112th's day was spent adjusting its defensive perimeter. The 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, took positions west of the supply drop zone to cover the rear of the 112th's defenses. The battalion's left flank connected with the cavalrymen's mortar platoon, which, in turn, tied into Troop F on the Driniumor. The 2d Battalion,

127th Infantry, established a line on high ground, tying into Troop E on the left, but exposed on the right. The perimeter resembled a large semicircle facing south and west. Meanwhile, small units maneuvered and countermaneuvered in search of each other. On 27 July, for example, Troop A and the 2d Battalion, 127th Infantry, attacked a suspected Japanese command post. American artillery cratered the area, so marching through the rain-filled pockmarks left everyone mud-soaked. The men met only scattered sniper fire. They reached the alleged location of the command post, found nothing, and continued to push another several hundred meters southwest, again

discovering no enemy soldiers. No one knew whether their "attack" had succeeded or not. All the Americans could do was return to their original positions, thankful no determined Japanese had lurked in the jungle along their route. Farther north, however,

there was renewed Japanese activity.

That morning U.S. patrols observed an estimated two companies of Japanese

digging in astride the trail from the drop zone to Afua, in effect cutting the resupply link

to the cavalrymen near Afua. A hastily organized attack by a platoon of Troop E and a

platoon from Company A, 127th Infantry, supported by the cavalrymen's mortar

platoon, drove off the Japanese. The mortar crews fired heavy concentrations in support

of the foot soldiers. Most of the thirty-five Japanese killed that day fell to mortar fire.

Five Americans were killed and six were wounded in the afternoonlong engagement.

The Japanese retreated about 135 meters, which sufficed to keep the vital drop zone-Afua artery open. Cavalrymen searched through the pockets and clothing of the abandoned Japanese corpses and discovered documents and personal identification associating the dead with the 66th Infantry, the first appearance at Afua to date of that unit.*

The fighting then slackened off in the 112th Cavalry's sector. Allied intelligence interpreted the scattered contacts as evidence that 18th Army's excessive casualties and lack of resupply spelled the end of its offensive. Consequently, U.S. analysts reasoned that the Japanese probably had begun to withdraw from the Afua area. [78]

Generals Adachi and Hall, however, were

simultaneously preparing operational plans for what they believed would be the decisive battle of the campaign. Neither general's scheme would come to fruition.

Chapter 7: Attrition

A Japanese advance patrol, usually four or five riflemen and a light machine

gun team, picked its way single file through the undergrowth. When they encountered an American patrol, gunfire might be exchanged, but more likely both patrols would scatter into the thick, tangled vegetation and redeploy in its cover. The Japanese riflemen would disperse to cover the flanks of their machine gunner. The Americans would bring forward automatic weapons to build up their firing line as they called for artillery or tried to outflank the Japanese. If the American artillery fire and movement were successful, the Japanese would flee, and the cavalrymen would move cautiously to finish off wounded Japanese. If the Japanese infantry proved too strong to expel, the Americans would withdraw, carrying their wounded and dragging their dead. As often as not, on first sight of each other, both sides would flee into the safety of the jungle.

On 26 July a light rain and overcast sky added to the problem of identifying fleeting shadows in the jungle. The Japanese took advantage of the morning mist and fog to mask the location of a battalion artillery piece, which fired several rounds that exploded near General Cunningham's

command post. The fragmented small unit fighting flickered on and off in the rain near Afua.

On 26 July a light rain and overcast sky added to the problem of identifying fleeting shadows in the jungle. The Japanese took advantage of the morning mist and fog to mask the location of a battalion artillery piece, which fired several rounds that exploded near General Cunningham's

command post. The fragmented small unit fighting flickered on and off in the rain near Afua. *The presence of 66th Regiment elements in this area was probably due to the necessity of using combat troops to serve as bearers to manhandle supplies to Miyake Force. The maneuver elements of the 66th Regiment were operating southwest of this location. According to a Japanese POW captured on 28 July, about fifty infantrymen from the 66th Regiment had been converted to ration bearers.

Chapter 7: Directives

Chapter 7: Miyake Force

Chapter 7: Regrouping

Chapter 7: Rescue of Troop C

Chapter 7: US Redeployment

Chapter 7: Japanese Flank Attack

Chapter 7: Japanese Change of Plan

Chapter 7: Aftermath

Back to Table of Contents -- Leavenworth Papers # 9

Back to Leavenworth Papers List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com