Miyake's screening patrols were in position by daybreak on 18 July. Shortly afterward, one of these patrols, operating about one mile west of Afua, ambushed a squad-size 112th Cavalry patrol that was reconnoitering the trail to River X. A point-blank burst of machine gun fire killed one cavalryman and scattered the Americans, who ran for cover in the jungle. Two or three Japanese light machine guns peppered the cavalrymen, but their officer had made radio contact with Troop A, which sent reinforcements. The Americans pinpointed the Japanese ambush positions and called for artillery and mortar fire.

After the high explosives saturated the Japaneseheld jungle, wrecking trees and cratering the area, Troop A assaulted the Japanese positions and killed six of the enemy. The remaining Japanese had already escaped east and north into the jungle. At the other end of the trail near River X, a detachment of cavalrymen proceeded only 400 meters before stumbling into a Japanese screen. This time it was the cavalrymen who gave up the fight first and made their way back to River X and safety. These patrol clashes pointed to the possibility of a Japanese attack.

Indeed the Americans were jittery, and there was a report (later proven false) that General Cunningham's command post was under attack. In spite of the indicators, the direction of the main Japanese attack caught the 112th Cavalry by complete surprise.

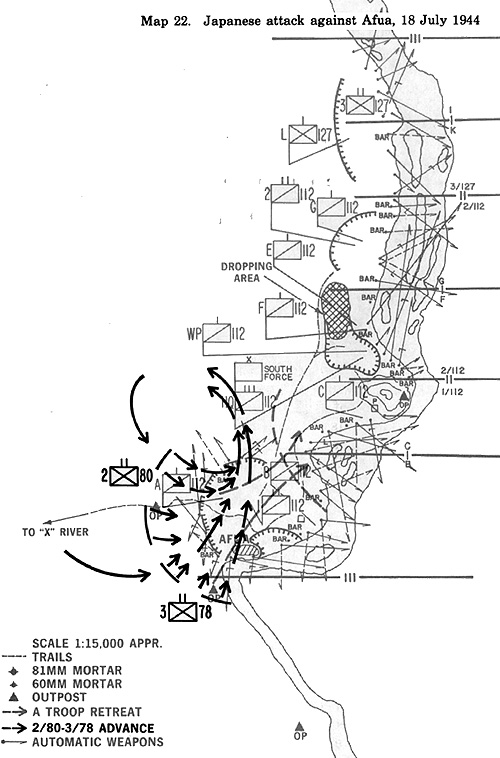

Cpl. Charles C. Brabham was settling into his nighttime defensive position, under a log on the Driniumor bank facing south. It was just before dusk, and having secured the perimeter and strung tin cans on the barbed wire for a crude early warning system, several men were bathing in the river. Suddenly a machine gun roared, and Japanese soldiers in skirmish line formation emerged from the jungle, walking and firing into Troop A's perimeter from the south and west (see map 22). The 112th Cavalry was being attacked from the rear in strength. Pfc. Walter Stocks, a rifleman, was sheltered in a bomb crater that served as an outpost.

He recalled, "One shot was fired and everything broke loose. Japanese fighting patrols, ten here, ten there, spreading out to flank. I called for artillery." His machine gunner dropped down into the crater, stunned by a Japanese bullet that creased his skull. The few other Americans in the crater fought back, and Stocks himself ducked into the crater with the wounded gunner, but still traversed the machine gun back and forth with one hand, spraying bullets at the menacing Japanese foot soldiers. A bullet hit Stocks in the hand. When a white phosphorus grenade exploded, the men in the outpost used the diversion to clear out with their wounded back to the main force. [66]

All the men in 1st Squadron knew was that machine guns and mortars were

blasting away behind them. Troop A took the brunt of the assault conducted by the Japanese 3d Battalion, 78th Infantry, and 2d Battalion, 80th Infantry. Despite heavy losses attacking across the Driniumor on 10-11 July and despite being out of supply and usually out of communication with other Japanese formations for the next week, the Japanese fought fanatically. The infantrymen were undernourished and exposed to torrential rain, mosquitoes, and insects. These particular troops had not eaten since the previous day and had been reduced to living on grass or tree bark. [67]

They were weary, and their uniforms were becoming ragged. They had seen

and felt the death or mutilation of hundreds of their comrades. But when ordered to attack, they advanced. It seemed the sheer desperation of their condition served to drive their attacks forward.

For two hours the struggle raged. A few men here and there appeared briefly out of the jungle or over the lip of bomb craters to fire several hurried shots at real or imaginary enemies. Intermittent showers and darkness compounded the confusion, but the Japanese capitalized on their initial surprise and forced the shaken troopers back about 300 meters to the north. Troop A used communications wire to guide its retreat. Like the ball of yarn that enabled Theseus to escape the Labyrinth, the communications wire became a lifeline that guided the cavalrymen and their sixteen wounded comrades to safety in the featureless black maze. Two cavalrymen had been killed.

With Troop A driven back, Troop B called in its upriver outpost, pulled its southernmost platoon from the Driniumor, and moved it southwest to protect Troop B's south and rear. Meantime, the Japanese moved northeast to their reassembly areas in order to reorganize after the attack. With the

cavalrymen retreating northwest and the Japanese regrouping northeast, contact between the combatants was severed. Nonetheless, the 112th Cavalry spent an edgy night, as illustrated by the fate of a courier who was making his way to Troop B around midnight.

The officer stumbled into a 112th Cavalry foxhole. Presuming he was Japanese, its occupants instinctively attacked and seriously wounded the lieutenant. In the middle of this confusion, General Cunningham had to sort out Troop A, reinforce it, and plan a dawn counterattack to retake the lost ground.

He used a platoon from Troop E, an antitank platoon of Headquarters Troop, and one rifle platoon from the 3d Battalion, 127th Infantry, to counterattack at 0700 on 19 July and retake Troop A's former sector. The attackers encountered almost no Japanese resistance and regained their previous day's positions. Patrols reported, however, that numerous small parties of Japanese troops were moving nearby in the jungle thicket. General Miyake had again rallied his decimated troops for a daylight attack

against the Americans. The opposing forces blundered into each other on the west side of Troop A's positions. The men of the 3d Battalion, 78th Infantry, had set up heavy machine guns in thick vegetation across a creek to the west and provided themselves enfilading fire with machine guns firing from a swampy area to the south.

The cavalrymen unwittingly walked into this ambush, suffered losses, and pulled back to await artillery support. The Japanese did not take advantage of the delay to redisposition themselves or to move against the Americans, perhaps because they thought help was on

the way from the northwest. Indeed, Japanese small arms fire was coming from that direction, but the elements were, at most, squad size. During the "considerable time" lost in coordinating American artillery fire, a platoon leader in Troop E, 2d Lt. Dale E. Christensen, ordered his men to stay under cover while he crawled forward through the jungle undergrowth to pinpoint the Japanese automatic weapons and to find a possible avenue of attack. Although Japanese small arms fire hit his rifle and knocked it from his hands, Christensen crept on until he found the machine guns. He used hand grenades to destroy one Japanese machine gun and kill its crew, after which he returned to his men.

Finally, American artillery began exploding among the Japanese positions, although the long-delayed barrage prevented the Americans from attacking until 1400. At that time, Christensen took his men to the point he had previously reconnoitered for the

attack and led their charge against the dazed surviving Japanese.*

Those Japanese who still could, fled into the jungle. The cavalrymen killed any Japanese wounded. This was the worst day of fighting so far for the 112th Cavalry. They had lost six men killed and twenty-nine wounded, mostly to Japanese small arms fire. Colonel Miller's personal count of Japanese corpses totaled 139. It had been a grim struggle, because the firm wills of their respective commanders had determined that both sides were to stand and fight, a rare occurrence in the tropical rain forest.

By late afternoon, Troop A had reestablished its original positions. There was no time to pause for congratulations. Tired and frightened men had to perform the most menial of tasks, such as burning the excrement in Japanese field latrines, which they rightly regarded as a source of possible disease. Litter teams carried out the wounded and the dead. Aside from the enormous physical energy required to carry a litter in the tropical heat and high humidity, the unarmed parties worked in constant peril of imminent deadly attack. The morning of 19 July, for example, four litter bearers of the 107th Collecting Company were combing the bush just north and behind Troop G's lines for American casualties. Suddenly, crashing through the bush, came a sword-waving Japanese officer or senior NCO who fatally slashed one litter bearer. Death or

maiming from accidents also increased as the cumulative fatigue dulled the men's senses.

Infantrymen were killed in accidents, like the one crushed to death when a C-47 dropped

free-fall rations and overshot the drop zone. In the middle of intentional mayhem, such

absurd accidents were especially cruel blows.

Combat on 18 and 19 July had almost destroyed the already decimated Miyake Force. Small groups of Japanese troops cut off in the daylight fighting tried to use the cover of darkness and heavy rains to recross the Driniumor to the east. One group of fifteen Japanese stragglers used its last mortar rounds, grenades, and light machine gun ammunition in a surprise attack to break through the north flank of the 3d Battalion, 127th Infantry, from the rear. One Japanese was shot to death in the attempt. The others made it through and left in their wake two dead and five wounded Americans. In the jungle the opponents were so intermingled within each other's formations that mortal enemies could be almost within arm's length of each other, yet remain unaware of the proximity. The conditions were at that moment worsening.

Chapter 7: Attrition

*For these and earlier actions, Christensen would be awarded the Medal of Honor.

Chapter 7: Directives

Chapter 7: Miyake Force

Chapter 7: Regrouping

Chapter 7: Rescue of Troop C

Chapter 7: US Redeployment

Chapter 7: Japanese Flank Attack

Chapter 7: Japanese Change of Plan

Chapter 7: Aftermath

Back to Table of Contents -- Leavenworth Papers # 9

Back to Leavenworth Papers List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com