Hall's preoccupation with his major counterattack probably resulted in less pressure on General Gill, Persecution Covering Force commander, to "mop up" Japanese resistance south of Afua. Gill, in turn, reluctantly agreed to General Cunningham's requests to reduce offensive operations in order to shorten his line to the north. Cunningham spent 28 through 31 July redeploying his forces, strengthening his new defensive perimeter, and sending out reconnaissance patrols to provide information

on the suddenly elusive Japanese. The gradual, if unavoidable, erosion of the combat units' fighting strength from battle casualties, accidents, and disease necessitated the

redeployment.

From 13 to 31 July, the 112th Cavalry had suffered 260 battle casualties, 17 percent of its understrength total. All told, South Force (2d and 3d battalions, 127th Infantry Regiment, and the 112th Caealry Regiment) had lost 106 killed, 386 wounded, 18 missing, and 426 evacuated because of disease or illness. [80]

The Americans estimated that they had killed approximately 700 Japanese

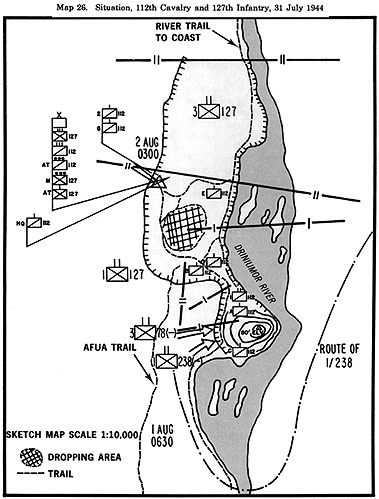

during the same period. In other words, in spite of the Americans' overwhelming materiel and firepower superiority, battlefield casualties were not that dissimilar. The nature of the terrain precluded the Americans from bringing their massive firepower to bear effectively. Instead, small numbers of infantrymen on both sides engaged each other in close combat of attrition, which inevitably resulted in high losses among the infantry. The men redeployed in a light rain on 29 July, and some, like Troop C, moved just after dark. Redeployment was hard work for men whose physical strength had been worn down by three weeks of continual combat, and they staggered under the weight of their packs and sloshed through the mud to their new positions. Once there, they had to erect shelters, dig latrines, and clear fields of fire-in short, they had to replicate the defensive hamlet they had built just a few days before. The dispositions on 31 July

resembled those shown on map 26. General Cunningham had stayed on the defensive and used the respite granted him by higher headquarters and the Japanese to strengthen the 112th's position along the river. His men reorganized and resupplied, Cunningham was now ready to attack the Japanese. His counteroffensive would open 1 August. Despite no prospect of resupply for 18th Army, its officers and men were confident about their upcoming attack on the American perimeter at Afua. If American

reinforcements isolated the Japanese attackers, there would be no alternative for 18th Army but to expend all its force in repeated

attacks to relieve them. According to the chief of staff, Lieutenant General Yoshihara, the forthcoming operation would be "literally a fight to the death." [81]

Japanese battle casualties and the chaotic Japanese logistics network made more than

one major attack impossible. The terrain and insufficient communications made the

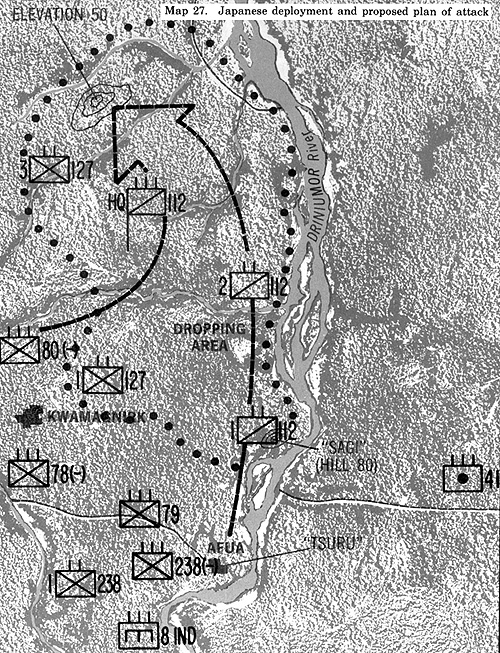

likelihood of a coordinated, concentrated assault remote. Japanese operational plans

called for the offensive to commence at dusk on 30 July. They envisioned the 20th

Division overrunning American positions at Afua and Hill 80, with the 41st Division

seizing positions on the Driniumor north of Afua. The 112th's withdrawal from its

southernmost position, the so-called Tsuru, caused Adachi to alter his plan, essentially

moving the objectives of the two divisions farther north, directly into the teeth of the

112th's newly established defensive positions.

Adachi's 29 July order clearly revealed his belief that this was 18th Army's final opportunity to snatch victory from the Americans. For the first time in the New Guinea campaigns, 18th Army instructed artillerymen "not to be frugal with ammunition." Everything would be wagered on this battle. [82]

Adachi detailed a rear guard between Kawanakajima and Yakamul to prevent

any American attacks through that area. This rearguard defense consisted of men from the 41st Division and "borrowed" combat service support troops from the 4th Field Transport Headquarters, plus one mountain gun and one 70-mm gun to aid in antitank defense.

This rear guard also constituted the force that would warn 18th Army of any major American counteroffensive or amphibious landing behind Japanese lines. The remainder of the 41st Division deployed south. By 27 July the troops were still several kilometers from their attack position, so 18th Army had to postpone the date of its projected attack until 1 August. Moreover, the whereabouts of the 239th Infantry were

unknown, Japanese scouts being unable to find it. The 238th Infantry finally arrived in its assembly areas the morning of 30 July; the 41st Artillery Regiment and 8th Independent Engineer Regiment, that afternoon; and the 1st Battalion, 238th Infantry, linked up with

the 79th Infantry that evening.

The next morning the 41st Division Headquarters joined the 239th Infantry. The Japanese artillery deployed on a ridgeline overlooking the Driniumor's east bank about halfway between Afua and Hill 80 in order to support the attacks on those American positions (see map 27). [83]

Rain made the trails over which the supply troops carried their heavy burdens

slick and muddy. A path that one day provided easy access to frontline units could turn

overnight into a quagmire or even disappear into the morass of mud, jungle, and bomb craters. Illness increased dramatically as the Japanese struggled to bring vital provisions forward. The tribulations of the rear service mattered little to the frontline Japanese fighters, who bitterly complained, "Our supply services kill more of us than enemy bullets."

[84]

In the face of such hardships, the Japanese had managed to concentrate the remnants of two infantry divisions and an understrength infantry regiment (perhaps 4,000 combat troops total) east, South, and southwest of Afua. The 112th Cavalry and 127th Infantry focused their attention on the southern flank, where they expected any Japanese attack to originate. Patrols searched west, south, and southwest for signs of Japanese activity. They found stragglers, whom they

killed, and well-armed, fully uniformed Japanese infantry, whom they avoided. Small groups of three or four Japanese stragglers appeared west of the cavalrymen's defenses, either scavenging in American garbage for food or discarded clothing or wandering almost in a daze through the jungle. Such preoccupied men were easier and safer to kill than to attempt to capture as prisoners.

A patrol working in the rear of 1st Squadron had indeed tried to take a Japanese prisoner, but the would be POW instead activated a hand grenade, pressed it to his chest

and killed himself. Stories of such fanaticism made the rounds of the 112th quickly and confirmed stereotypes of Japanese and the risks involved in taking prisoners.

Patrols to the south did not run into ragged stragglers. They caught glimpses of well-equipped Japanese combat troops. A heavy rain on 29 July restricted visibility, but in their potentially lethal game of hide-and-seek, patrols continued to report enemy sightings. The next day, American patrols operating near Afua, vacated the previous day by 112th, reported Japanese soldiers already occupying foxholes in the shell-marked village. Other patrols found the partially decomposed remains of Japanese corpses or the mutilated victims of artillery fire, occasionally as many as ten dead at one location. It was grisly, ghoulish work to pry weapons or personal items from these stinking corpses that fell apart when touched. It had to be done, however, because higher headquarters

demanded information that might identify the Japanese units arrayed against South Force.

An order for such information resulted in a Troop A combat patrol being sent

east across the Driniumor to search for Japanese. Their faces chapped and weathered by

the sun, their uniforms ragged and caked with dirt, sweat, and grease, the men were absorbed by the lush jungle growth. They proceeded in column formation at dispersed interval, so each man could just see the back of the man in front of him. As the Americans tramped southeast on a native trail, two Japanese soldiers fell into the rear of the column and apparently marched along with the patrol for some time, both sides

unaware of the presence of their enemies. Perhaps it was indicative of the effect of the tropical rain forest on the opponents. Boots falling apart from continual immersings in water and pounding on the rugged terrain, uniforms tattered and stained black with sweat, exposed skin burned, darkened, and soiled, all combined to make Japanese and American combat

troops indistinguishable in outward appearance. This strange procession abruptly ended when a cavalryman finally noticed the Japanese behind him. He shouted a warning and in response one Japanese threw a grenade at the Americans, and both then escaped unharmed into the jungle. The cavalrymen, also unharmed, continued their long patrol.

Chapter 7: Attrition

General Hall at XI Corps Headquarters on 29 July decided to counterattack 18th Army. Two days later, three U.S. infantry battalions would attack on line from the coast to about 2,300 meters inland. At Niumen Creek, about 2,700 meters to the east, the battalions would turn south to envelop the Japanese still, fighting around Afua. [79]

General Hall at XI Corps Headquarters on 29 July decided to counterattack 18th Army. Two days later, three U.S. infantry battalions would attack on line from the coast to about 2,300 meters inland. At Niumen Creek, about 2,700 meters to the east, the battalions would turn south to envelop the Japanese still, fighting around Afua. [79]

In contrast to the 112th's relatively smooth redisposition, the 41st Division had to conduct its redeployment under constant Allied bombardment and while dealing with jungle obstacles. Australian and American warplanes dropped tons of bombs along suspected Japanese trails, and Allied warships shelled suspected "Japanese troop concentrations." Japanese supply troops in transportation units labored under the same danger, but over much longer distances.

In contrast to the 112th's relatively smooth redisposition, the 41st Division had to conduct its redeployment under constant Allied bombardment and while dealing with jungle obstacles. Australian and American warplanes dropped tons of bombs along suspected Japanese trails, and Allied warships shelled suspected "Japanese troop concentrations." Japanese supply troops in transportation units labored under the same danger, but over much longer distances.

Chapter 7: Directives

Chapter 7: Miyake Force

Chapter 7: Regrouping

Chapter 7: Rescue of Troop C

Chapter 7: US Redeployment

Chapter 7: Japanese Flank Attack

Chapter 7: Japanese Change of Plan

Chapter 7: Aftermath

Back to Table of Contents -- Leavenworth Papers # 9

Back to Leavenworth Papers List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com