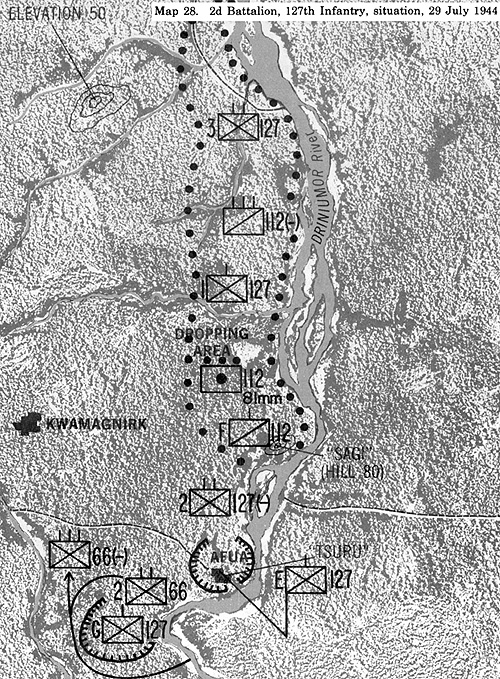

Amidst this extensive patrolling, a major action occurred on 29 July, when the 2d Battalion, 127th Infantry, deployed to reoccupy its former positions southwest of Afua. It ran directly into the 66th Infantry, which was in the process of attacking northeast against the Americans. Once again the meeting engagement broke down into a series of small, isolated combats, with both sides under the impression that they were

attacking the defensive positions of the other.

Amidst this extensive patrolling, a major action occurred on 29 July, when the 2d Battalion, 127th Infantry, deployed to reoccupy its former positions southwest of Afua. It ran directly into the 66th Infantry, which was in the process of attacking northeast against the Americans. Once again the meeting engagement broke down into a series of small, isolated combats, with both sides under the impression that they were

attacking the defensive positions of the other.

The Americans, as had now become a standard tactic, called for all available artillery support, but as the shells crashed into the area, the light rain and mist made accurate spotting nearly impossible. After shelling a point for several minutes, the artillery would lift, and the infantry point would cautiously move forward. If any Japanese fired on them, the Americans would quickly pull back and restart the artillery bombardment. The Japanese seemed to the Americans to be withdrawing, but the 66th Infantry was maneuvering away from the lethal artillery fire and around the right (west) flank of the 2d Battalion (see map 28).

Maj. Okamoto Takahisa, commander of the 3d Battalion, had the mission to envelop the American positions threatening the 20th Division's flank near Afua from the east and then to attack south. In theory, the attack would carry to the American position known to the Japanese as Sagi, an eightyfoot elevation about 900 meters northwest.

As the 3d Battalion advanced, it bumped into the U.S. 2d Battalion, 127th Infantry, which immediately called in massive artillery fire. With artillery exploding all around them, the Japanese suffered several casualties. In the din and smoke, confusion reigned, and Okamoto had to run around urging or kicking his troops to get them to move forward. Okamoto's 3d Battalion was on the extreme right (west) Japanese flank, and he was the only officer who had a map of the area. His company commanders used compasses to guide their path through the foliage.

All contact among Japanese units disappeared into the green wall of vegetation

they were struggling through. The jungle terrain had fragmented Okamoto's forces,

leaving him with no idea how the neighboring company was faring. Instead, small parties

of Japanese collided with small numbers of Americans, deployed, and attacked their

enemies. [85]

Okamoto's men wedged themselves between Companies E and G, isolating

these Americans from their battalion, just a few hundred meters away, as the jungle again swallowed entire formations into itself.

When General Cunningham, as South Force commander, ordered the 2d

Battalion to withdraw at 1800, Company G instead remained on its high ground because of Japanese infantrymen lurking in the vegetation to its rear. Company E also preferred to remain in place because of "the uncertain situation and the danger of being fired on by

our own troops." [86]

Company E had lost thirty-nine men killed or wounded during the day, including several when a friendly mortar round dropped short. The rest of the battalion withdrew north, but was ambushed and

attacked by Japanese from the 66th Infantry, who were still advancing east to west. The Americans predictably called on all available artillery support to place a curtain of fire between themselves and the Japanese. The 2d Battalion reported that twenty-six Japanese had been killed by artillery fire. [87]

SWPA G-2 assessed the action as characteristic of Japanese inflexibility regardless of losses suffered and indicative of "an apparent lack of control being exercised over enemy operations in the Driniumor sector."

[88]

Unbeknownst to the fighting men, the respective commanders had already set in motion another train of events that would climax the Driniumor battles. General Hall's enveloping maneuver, the so-called Ted Force Action, commenced on 31 July, as four American infantry battalions crossed the Driniumor and advanced east.

According to intelligence, the order began, there was some doubt that the enemy had begun its retreat. Eighteenth Army would continue attacks to annihilate the enemy by advancing northwest to a line from Sagi to north of Elevation 50. In the second phase, the 41st Division would roll up the northern American flank on the Driniumor.*

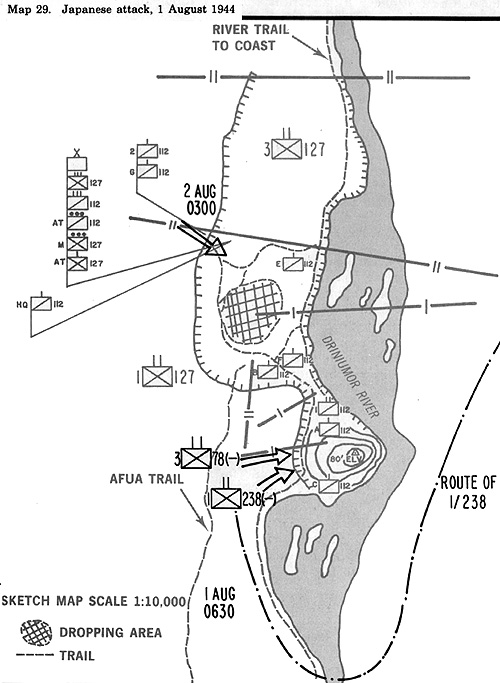

At Sagi, Lt. Col. Clyde S. Grant, the new commander of 1st Squadron, 112th Cavalry, organized his perimeter in a lazy-S configuration, with Troops B, A, and C deployed north to south and facing west. He also had a machine gun platoon and reinforcements from Troop E. The battle position was just east and around a low hill (Elevation 80) that had many fallen trees scattered around from the continual artillery pounding. The heavy tree trunks and thick vegetation bordering the perimeter made it impossible to clear fire lanes in the area. The men resorted to hammering aiming stakes into the ground to enable them to fire at a particular spot during a defense. [89]

Just before dawn on 1 August, Maj. Imamura Hideo and the 1st Battalion,

238th Infantry, approached Grant's defenses from the southwest after crossing the Driniumor near Afua (see map 29). The battalion was to join forces with the 3d Battalion, 78th Infantry, on its left (west) and seize Sagi. Point men cautiously moved forward, while infantrymen trailed about thirty-five meters behind, with the regimental commander, who led their advance, carrying the regimental colors. Americans in outposts heard the Japanese approaching from the jungle and withdrew. This movement created the impression among the Japanese point men that all the Americans were withdrawing, and a garbled report to regiment added to the perception that Sagi had already fallen. Regimental headquarters personnel quickly moved forward to capitalize on the American

"withdrawal." A few minutes later, an earsplitting roar of gunfire and explosions burst from the direction of the Japanese advance. American artillery shells began exploding all around the Japanese still in the jungle.

Capt. Karai Keiji, commander of 4th Company, 1st Battalion, 238th Infantry, led the attack against Troop C. Karai and his men had been living on parched rice for the past two days, and their greatest ambition was to break into the American positions to steal food and rations. They had been on the move since 0200. Karai urged his weary men forward until they arrived at the fringe of the jungle, about 100 meters outside Troop C's log-strewn perimeter.

All coordination among the Japanese units had dissolved during their night approach march. Consequently, it was left to each company commander to decide individually when to attack the Americans. Once firing began, the Japanese, packed together on a seventy-meter front, rushed like a wave from the jungle. Even in the frenzied attack, few Japanese lived to cover those last 100 meters to Troop C's lines.

The infantrymen from 4th Company were hit with a hail of small arms and automatic weapons fire in volleys from well-prepared defenses. Even unaimed American fire into the overcast predawn darkness and rising jungle mists could hardly miss the swarms of

two or three hundred Japanese screaming and running at them.

Next, artillery and deadly 81-mm mortar fire exploded immediately in front of Troop C's sector, shredding the Japanese ranks. The 1st Battalion commander died as a shell exploded almost on top of him. The bewildered Japanese survivors fled into the jungle, where First Lieutenant Ishiwara, commander of the Machine Gun Company, tried to rally the men, make them dig in, and launch another attack that evening. But there was no adequate cover from artillery, and small arms fire had stripped off much of the vegetation.

The Americans poured fire at anything that moved, making it dangerous even to burrow into the dirt. After about an hour of the one-sided fight, concentrated American mortar fire began to saturate Captain Karai's forlorn position. By then about half his men were dead, killed in the artillery maelstrom that had swept over 4th Company. Other Japanese attackers had suffered proportionately, and men were still being killed and wounded. The Japanese had lost perhaps 150 men, while Troop C suffered five killed and six wounded. There was nothing for Captain Karai to do but to escape.

In groups of two or three, the beaten Japanese infantrymen melted back into the safety of the deep jungle. That night Lieutenant Ishiwara killed himself to atone for the debacle. Next morning Major Imamura scouted near the alleged Japanese front line, but was unable to locate a single living Japanese soldier. A few stragglers drifted by throughout the day, more often than not with tales of officers and wounded men committing suicide. Only a handful of Japanese soldiers had

ever reached Troop C's lines, and they were killed in hand-to-hand combat. [90]

The cavalrymen in Troop C looked out on piles of Japanese corpses and, while still shaken from the violence of combat and the loss of comrades, realized that they had smashed the attackers. Medics and litter bearers moved to Troop C's area to assist with

the removal of the wounded and dead. The Japanese attack had made General

Cunningham's planned offensive unnecessary. Instead, he ordered Troop G to attack southwest through Troop C's positions. The attackers advanced at 0830 and moved 600 meters against only scattered sniper fire. The Americans killed twenty-seven more Japanese, most of them dazed and confused stragglers trying to flee the carnage. There

were no U.S. casualties. Troop A, just north of Troop C, had the distinction of capturing the first Japanese prisoner ever taken by the 112th Cavalry. The prisoner related the destruction of his battalion from the 238th Infantry and revealed that shortly another Japanese battalion would arrive near Afua.

If fortune had smiled on most of the 112th early that day, by afternoon and evening it had deserted them. A Japanese mortar crew firing from the vicinity of the 41st Artillery Regiment dropped about fifteen rounds near the 112th's command post, wounding three men in Troop F. Friendly fire called on to suppress the Japanese gun fell short into Troop E's left flank and wounded three more Americans. Self-inflicted suffering continued that night. About 0300 a small Japanese patrol blundered into Troop G's rear sector on the southwest edge of the dropping zone. In the ensuing melee, Japanese bullets wounded two cavalrymen.

Then both sides drew back, regrouped, and the fight erupted again as the

Japanese continued their probes. The cavalrymen called for mortar support, but one round of a 60-mm concentration either clipped a tree branch or had a faulty fuse and fell short, killing the 2d Squadron surgeon and two cavalrymen, as well as wounding two more.

But that long night witnessed even more "friendly fire" casualties. Troop F riflemen mistakenly shot five members of their artillery liaison party. The artillerymen had left their foxholes during the fighting to set up a radio, their phone communications having been severed. Their failure to answer the troopers' challenges resulted in two more Americans dead and three wounded by their own comrades. At first light, the Americans discovered one dead Japanese, two abandoned light machine guns, several rifles and helmets, and numerous trails of blood.

About mid-morning on 2 August, a 112th patrol moving towards the Driniumor walked into a Japanese bivouac and had to shoot its way out. Five more men were slightly wounded. In addition to battle casualties, General Cunningham also had to worry about disease, as medical evacuations for illness were doubling every ten days. It appears that the men of the 112th Cavalry had reached the limit of their endurance. But as long as the battle

raged, there could be no relief for the fighting men. Postwar reports recognized that men might fake illness or try to reach safer rear areas. Others became fatalistic, failed to take ordinary precautions, and were convinced that they were the only persons the war required to "take it" day and night until they "got theirs." [91]

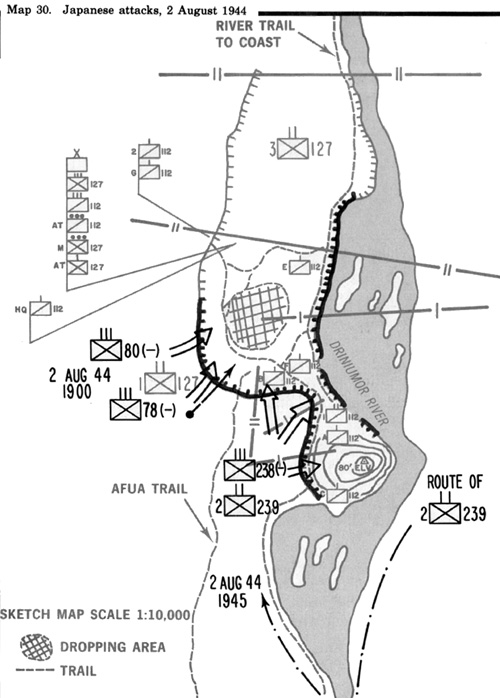

On the afternoon of 2 August, 18th Army issued orders to continue the attack against South Force. The 20th Division, now reduced to about fifty men in the 80th Infantry and perhaps sixty or so in the 78th Infantry, would combine their forces into a single command and together with the 41st Division strike the rear (west) of the American positions near Hato, then defended by the 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, and 1st Squadron, 112th Cavalry (see map 30). The Japanese struck initially against the 1st Battalion.

Major Kawahigashi again led his battalion into the attack. His troops were low on ammunition and knew that they could not neutralize the overwhelming American firepower. They devised a plan to avoid it. Masked by dusk, they would simultaneously fire all their grenade dischargers, mortars, and one battalion gun. The surprise and subsequent shock action of a massed infantry assault on a narrow front, the Japanese believed, would temporarily unnerve the American defenders. This paralysis would give the Japanese the time that they needed to cross the killing zone in front of the U.S. lines and to break into the American defenses, where the U.S. artillery could not be used against them.

Men of the 78th Infantry had dragged a 70-mm howitzer through the jungle to within twenty meters of the 1st Battalion's lines. The gun fired point-blank into the American lines to signal the attack, but on the first round, the gun flipped upside down. Japanese attackers, packed together, came running from the jungle screaming. American small arms fire and artillery explosions riddled the dense mob.

Despite Japanese jamming of the American artillery communication channels and the absence of any artillery observers, the 120th and 129th Field Artillery battalions pounded the area outside the 112th's perimeter. Cavalrymen called artillery fire to within fifty meters of their lines. Other Japanese troops tried to crawl along the ground toward

the American lines to escape the withering fire. Kawahigashi saw that the Americans fired at anything that moved.

In the rapidly fading light, Japanese camouflaged with tree limbs and leaves collapsed after several bullets struck them. Darkness settled as flares lit up the sky, revealing the carnage. The attack failed, though not for lack of fanatical courage, as all the 78th Infantry's remaining

company-grade officers died leading their men in this assault.

[92]

Wounded Japanese soldiers began to commit suicide with hand grenades, adding to the slaughterhouse in front of the 1st Battalion's positions, where the defenders counted fifty-eight Japanese corpses.

About forty-five minutes after that assault had begun, survivors of the 41st Division hurled themselves at the adjoining 1st Squadron, 112th Cavalry. For the first time in the campaign, the cavalrymen occupied a well-organized defensive perimeter. The Americans could fire their 60-mm mortars effectively and had automatic weapons sited every twenty-five meters or closer. It was a formidable defensive position. The Japanese attackers from the 41st Division had underestimated it.

Chapter 7: Attrition

At 1400 the same day, General Cunningham issued a warning order to Troop G and Company K, 127th Infantry, for an attack south and southwest against the Japanese to commence at 0800 the next day. General Adachi, meanwhile, revised his attack plans to conform to the confused, but apparently fluid, battlefield situation. On 29 July the 20th Division reported that it had driven the Americans from Tsuru (Afua) and that they were mopping up that position. Indeed, Cunningham had ordered the withdrawal from

Afua that day. The 66th Infantry's fight of 29 July near Afua also influenced Adachi's attack order issued the afternoon of 31 July.

At 1400 the same day, General Cunningham issued a warning order to Troop G and Company K, 127th Infantry, for an attack south and southwest against the Japanese to commence at 0800 the next day. General Adachi, meanwhile, revised his attack plans to conform to the confused, but apparently fluid, battlefield situation. On 29 July the 20th Division reported that it had driven the Americans from Tsuru (Afua) and that they were mopping up that position. Indeed, Cunningham had ordered the withdrawal from

Afua that day. The 66th Infantry's fight of 29 July near Afua also influenced Adachi's attack order issued the afternoon of 31 July.

*The 41st Division staff officers unanimously disagreed with 18th Army's attack plans but were curtly told, "Even though there are differences of opinion, make the attack."

Justified as such thoughts might have been in their role, dwelling exclusively on them led to nervous breakdown. The cumulative fatigue of battle also dulled some of the men's reflexes, deadened their senses, and made what a few days before were normally simple, routine jobs almost unbearably complicated. Mistakes in a line combat outfit invariably swelled the friendly casualty list. Ironically, the men who had been most exposed to death and danger and had lived through it were now regarded as the experienced fighters and thus irreplaceable on the firing line. For them there was no way out.

Justified as such thoughts might have been in their role, dwelling exclusively on them led to nervous breakdown. The cumulative fatigue of battle also dulled some of the men's reflexes, deadened their senses, and made what a few days before were normally simple, routine jobs almost unbearably complicated. Mistakes in a line combat outfit invariably swelled the friendly casualty list. Ironically, the men who had been most exposed to death and danger and had lived through it were now regarded as the experienced fighters and thus irreplaceable on the firing line. For them there was no way out.

Chapter 7: Directives

Chapter 7: Miyake Force

Chapter 7: Regrouping

Chapter 7: Rescue of Troop C

Chapter 7: US Redeployment

Chapter 7: Japanese Flank Attack

Chapter 7: Japanese Change of Plan

Chapter 7: Aftermath

Back to Table of Contents -- Leavenworth Papers # 9

Back to Leavenworth Papers List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com