From the Lez River, Hannibal's army marches eastward across "open country" [Livius XXI, 32] heading towards the Alps. He comes back to the Aygues River somewhere around Nyons in the low foothills of the Baronnies and continues heading east into steeper and steeper terrain until reaching present day Remuzat-Rosans area. This is where the terrain becomes much more difficult.

From the Lez River, Hannibal's army marches eastward across "open country" [Livius XXI, 32] heading towards the Alps. He comes back to the Aygues River somewhere around Nyons in the low foothills of the Baronnies and continues heading east into steeper and steeper terrain until reaching present day Remuzat-Rosans area. This is where the terrain becomes much more difficult.

From the Island to this Ascent of the Alps spot measures a b o u t 130-140km, tallying nicely with Polybios' number of 10 days covering nearly 800 stades (140km). Here, Hannibal faces another challenge. Livius is his usual descriptive self, noting the dangers of the terrain, the local tribesmen "with their wild and ragged hair" who lived in "rude huts clinging to the rocks," and "other sights of horrors that words cannot express." [Livius XXI, 32]

As the Carthaginians advance, Hannibal finds local tribesmen holding a defile, likely halfway between modern Rosans and Serres. His guides discover the natives abandon the defile at night. Sure enough, Hannibal begins the ruse of fortifying a camp and turning in for the evening, only to capture the heights at night with a picked force, and start the movement of the army through the defile.

At daybreak, the tribe returns to find the Carthaginians on the march through the defile. Although the resulting ambush disorders the Carthaginians and causes heavy losses, Hannibal's swift counterattack from above routs the natives and ultimately, succeeds in taking the native's unnamed village--quite likely Serres.

For three days, Hannibal marches in peace through the ever-higher mountains until reaching another tribe, only this one is more devious and treacherous than the last. It is about 41 km (about 14km per day) from Serres to modern Gap which in ancient times was in the locale of the Tricorii tribe.

On the fourth day, the Gaulh offer Hannibal peaceful passage and guides. They had heard of his victory at the last defile and wanted nothing more than to allow the Carthaginians to move along. Hannibal is not so gullible, bu accepts the offer anyway, even as he alters his marching order.

It is unclear whether the army halted on this fourth day, but likely not. The tribe had no intention of attacking it the open, negotiations would not have taken very long, and Hannibal's in hurry. For two more days, Hannibal's army marches eastward towards the Alps until they've rejoined the Way of Hercules and get to the area around modern Guillestre (43km). No word is mentioned about the original Boi guides. Either they perished somewhere between the Rhone and here, or had been sent back to Italy to announce Hannibal's coming. In any case, there's not a loyal guide who evidently recognizes the Way of Hercules.

In any case, the Carthaginians are following the local guides, and these divert the Carthaginian army eastward up a side valley, the Combe du Queyres, towards modern Chateau Queyres instead of continuing on the Way of Hercules over the Mont Genevre pass. They lead Hannibal into a trap.

Up the Queyres valley is a "steep and precipitous defile" [Polybios III, 52] perfect for an ambush. The tribes gather and attack the rear of the Carthaginian column. Here, Hannibal's prudence regarding his marching order pays dividends. With most of the baggage up front and the key fighting units behind, Hannibal holds off the attack, even as it comes from above where the tribesmen "rolled down rocks" from above [Polybios III, 53] and attacked front, flank, and rear.

The Carthaginians suffer severe losses as they try to move through the gorge and resulting ambush. Indeed, the column is cut in two and Hannibal must remain with his rear guard overnight "near a certain bare rock which offered some protection." [Polybios III, 53] At the head of the valley, after a narrow gorge perfect for an ambush spot, sits the Chateau Queyres atop a prominent mini-mountain. Take away the medieval fortress and it looks like a perfect "rock" to establish a defensive position.

The next day, Hannibal and his rear guard catch up with the head of the column. Although harassed by occasional raids (and repelled with help from the elephants), Hannibal winds his way upwards to a pass obviously known to local tribesmen. Here, at the pass, located to the left of Mount Viso, Hannibal halts for a couple days to rest his troops and await stragglers. This "Pass of Hannibal" fits all the written descriptions of the ancients.

It is the Col de Traversette.

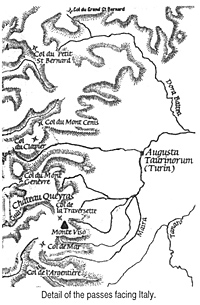

From Queyres to the Col de Traversette is relatively easy country to march. Most important is the height of the pass, both authors say that the pass was covered in snow the year round and the Col de Traversette, at 3000 meters, is high enough for new snow to overlay last year's snow. Next is the descent, which is as difficult and precipitous as described in Polybios and Livius. Third is an area for around 32,000 troops to bivouac and about 1.5 km from the summit, is a large plateau that would allow Hannibal enough room to camp 30,000 troops, horses and elephants. while his engineers widened the summit, (which today it is ten meters wide). Fourth is a view to Italy, and indeed, the Col de Traversette does have a spectacular view of the Po. Fifth, it exits from the valley and is generally a straight path into the territory of the Taurini, (I.E., directly to Turin).

From Queyres to the Col de Traversette is relatively easy country to march. Most important is the height of the pass, both authors say that the pass was covered in snow the year round and the Col de Traversette, at 3000 meters, is high enough for new snow to overlay last year's snow. Next is the descent, which is as difficult and precipitous as described in Polybios and Livius. Third is an area for around 32,000 troops to bivouac and about 1.5 km from the summit, is a large plateau that would allow Hannibal enough room to camp 30,000 troops, horses and elephants. while his engineers widened the summit, (which today it is ten meters wide). Fourth is a view to Italy, and indeed, the Col de Traversette does have a spectacular view of the Po. Fifth, it exits from the valley and is generally a straight path into the territory of the Taurini, (I.E., directly to Turin).

The descent is a battle against the elements, and to a certain extent time, although Hannibal won his race against the closing of the passes. It takes a day to rebuild a section of the path obliterated due to a landslide. Then the mule train and horses move on and are released into Italian pastures.

Three days and a widened path later, the elephants and the rest of the army join them.

The big argument against the Col de Traversette, is that is a small pass, difficult to reach, and does not have the room to hold a large army. Does that sounds like a good spot for treacherous guides to lead them to?

(Editor's note: Apparently it was also a favored pass of smugglers and this too discouraged a scholar's investigations. Nobody wishes to be killed over scholarship verification.)

However if one follow Hannibal's movements using the logic and experience of the great captain, plus the written accounts of the description of the pass, it would appear that this is indeed the pass of Hannibal.

Hannibal Crosses the Alps A Route Examined and a Proposed Alternate Route

-

Introduction

The Sources

Hannibal's March: Polybios and Livy

Polybios vs. Livy: Debate Over Details

A New Route Proposed: Begin at the End

A New Route Proposed: Start at the Beginning

A New Route Proposed: Where is the Druentia?

A New Route Proposed: The Pass in the Alps

Aftermath, Conclusion, and Bibliography

Back to Strategikon Vol. 2 No. 1 Table of Contents

Back to Strategikon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by NMPI

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com