Hannibal may have gotten a slightly later start than expected by waiting for his troops to assemble from winter quarters. He crossed the Ebro and headed towards Gaul, subduing tribes in between the Ebro and Pyrenees. As part of this campaign, he took losses of some significance, which also caused further delay.

Still, the march proceeded through the Pyrenees, and thanks to diplomacy, overwhelming force, and bribery, placated the tribes enough to let him pass unmolested along the coast. At some point before reaching--or upon reaching--the Rhone River delta, he cut away from the sea and moved inland to a spot where the Rhone River is but a "single stream" [Polybios].

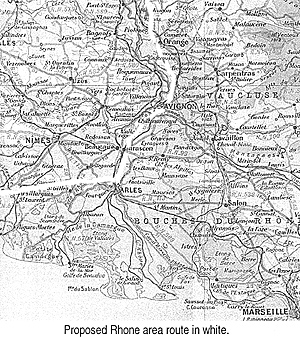

Though he may have been a bit behind schedule, he still estimated he was ahead of any Roman army and still had to bypass Massilia. Indeed, Polybios specifically says Hannibal arrived at the river..."long before anyone [anyone Roman, that is] expected him." He crossed at the first available place: Arelate (Arles), a place whose name means in Celtic, "near the marshes" [Polybios Book III 42.]

Returning now to Hannibal's intentions. He was marching along a coast he had not visited, and there is no mention of guides. He's trying to get to Italy the quickest way possible, but also to bypass Massilia. And that means hugging the coast until he gets to the first big river, then turns upriver until he finds a place at the apex of the delta where there's a crossing spot at a "single stream." Those four days, at what you'd call a standard march rate of 14km per day, bring him to Arles. It is roughly 50km away from the coast, well within striking distance, and indeed, the first usable crossing place of the Rhone as single stream.

However, the local tribe, the Volcae, decided to contest his crossing the Rhone River--if not the entirety of the tribe, for many of them happily sold the Carthaginians boats, then at least enough of them to form a significant force to oppose his crossing. Acting with cleverness, and with a stratagem similar to Alexander's opposed river crossing at Jhelum over 100 years earlier, he sent a subcommander upriver to cross over the river and take the tribe in the flank and rear while he crossed with the main army. The Carthaginians routed the Volcae and Hannibal crossed the Rhone, though it took considerable effort to get the elephants across.

It took six days from the time Hannibal arrived at the Rhone River until the time he crossed it. On the seventh day, he learned of the Roman Army at Massilia, some 80km away, and sent the Numidian horsemen to do a scouting. They came back soon, having met the Roman scouting force "quite near their camp," and with Roman cavalry hard on their heels. The Romans surveyed the Carthaginians and headed back towards their own army.

The scouting towards Massilia makes sense. Hannibal knew the city was where the Roman army would likely come from, as the coastal road went from Italy to the port city. Whether the Romans marched by land or transported by sea, they would end up near Massilia.

However, of note is the Roman reconnaissance force. Although not explicitly stated in either historian's work, someone from the Volcae must have hightailed it to Massilia to tell the Romans that 50,000 Carthaginians were about to force a crossing of the Rhone. This seemed to surprise the Romans, who may very well have thought the messenger delusional. Scipio, a pragmatic Roman, sent a group of cavalry to the crossing point anyway to confirm or deny the report.

Publius Cornelius Scipio often receives credit from historians for sending his army on to Spain (the original destination when he set out from Rome) instead of pulling it back into Italy when he learned Hannibal gave him the slip. How different the Second Punic War would have turned out had Scipio immediately marched his entire army to the crossing point instead of sending a cavalry force. Remember, the army marched for three days to get to the Rhone point.

Presumably, the cavalry took at least two days (if not three) to reach the spot 80km from Massilia, then two days (if not three) to return. Scipio's army would have arrived too late, to intervene, an apologists view from a patriotic writer, and in the case of Polybios, a Scipio-backed writer, is open to speculation.

(Ed. Note: Since P. Cornelius only had a force that could be carried by 60 quints [Polybios, Book III 41] we are looking at about 8500 men, in other words a legio and an socii ala. Even with allies from friendly tribes and the Greek levy from the city, the Roman army would come in around 20,000 untrained soldiers except for the legio. Hannibal had 50,000 hard bitten African and Spanish veterans of the Spanish campaign. I feel one can forgive Cornelius for not rushing to his destruction.)

In any case, by the time the Roman cavalry returned and Scipio marched the army for three days from Massilia, Hannibal was gone. Indeed, Polybios reports that Scipio was surprised that Hannibal had headed inland in an attempt to cross into Italy by a route other than the coast road. Evidently, Scipio was surprised several times during the campaign, once that Hannibal was even near the Rhone and a second time when the Carthaginians headed upriver. Scipio refused to follow and turned the army around to head back to Massilia.

(Ed. Note: If the forces were comparable, Scipio would have followed picking off stragglers. That was a common Roman tactic.)

Hannibal spent four days from crossing the Rhone to "The Island." From the distances given by Polybios, it would be about 600 stade, or about 105km. The average daily march was about 10km per day over the entire five months, and after leaving The Island, the Carthaginian army would average 14km per day. The 105km divided by four (days) equals about 26km per day. This average seems high, but a 50 percent boost in marching speed, or about 21 km per day, would not be out of the ordinary, and indeed, seems reasonable.

In any case, if Polybios' numbers are correct, a spot about 100km upriver was where the terrain turned into something looking like the Nile River Delta with the Rhone River as one side and the Skaras or Arar River on the other. Furthermore, there are almost inaccessible mountains forming a base between the two rivers. With a more conservative marching speed of 21 km per day, then you're looking for a spot 84km upriver.

This Island, or more correctly, a location 80-100km upriver at a spot where two rivers meet, is usually placed at the confluence of the Aygues, Drome, or Isere River. The Durance can be eliminated because it's too close, lacks the mountainous range, and does not fit the triangular description. Certainly the philologists have had a field day in proclaiming each of these rivers to be derivations of Skaras or Arar.

Are the two four-day periods equal? Is the distance marched four days from the sea equal to the distance four days from the crossing of the Rhone? Under normal marching, the answer is likely, "yes," making a spot about 56km from the crossing. That spot would be around Avignon, if the army kept to the river. But Polybios specifically notes 105km, or almost twice the normal march distance. Could Hannibal push his army that far, that fast?

Scipio apparently did. He marched a Roman army roughly 80km in three days, or almost 26km per day, which is roughly the distance we are to believe Hannibal's army matched. It was a well-trod route and his supplies moved via river boats, which helped his marching speed.

Hannibal was in a hurry and deployed his elephants and cavalry as a rearguard, no doubt primarily to see if the Romans followed, but also to ensnare any stragglers. Marching like a "thunderbolt" at twice as fast as normal, or 26km per day, even with mostly veterans, will likely result in straggling. The Carthaginians had fought a battle across a contested river, had to consider additional hostile tribes, followed a less developed track, and Hanno's subset of light troops marched even farther in a day. Neither Polybios nor Livius mention battle or marching fatigue. Hannibal could not afford to bleed his army through attrition, and he had no idea that the Romans would not follow.

With this in mind, consider 26km per day a top speed. A more reasonable 50 percent boost to the base 14km per day, or 21km per day, especially through less than improved areas, seems justified. The four day march certainly exceeded the 50-55km or so from the sea to the crossing of the Rhone.

The Island

It is interesting to note that the area Polybios chose to call the Island is similar in size and shape as the Nile Delta. If he had traveled the locale, why not call it the size and shape of the Rhone Delta? Is it because more readers knew the size and shape of the Nile versus the Rhone, or is it because the Nile was even more remote, possessed an atmosphere of mystery and grandeur, and would spice up a tale? Polybios would disavow the latter, noting that a historian should tell facts and write a pragmatic history. Yet, he is not above embellishment. Should we then interpret other parts of Polybios, which we know to be hyperbole, similarly--for example, his pointing out the plains of the Po? Is it a literal spot or a figurative allusion?

In any case, since he makes a particular point about the Island. If we take him at close to his word, we need to locate a large, well-cultivated, well-populated area between two rivers with delta-like conditions of multiple waterways and a base of inaccessible mountains.

Livius provides other clues. The Island must be at a place where Hannibal can then march into Tricastini territory and past Vocontii and Tricorii territories. Too far upriver and Hannibal has missed the territories. Polybios makes no mention of these specific tribes.

Livius further states the Druentia River has to be crossed. Arausio (present day Orange) sat on a hill rising 300 feet above the plain. According to Strabo, in pre-Roman times, Arausio was one of the centers of the Cavares Confederation. In 35-33BC, Octavian (Augustus) established a colony of ex-legionaries there--on land taken from the Tricastini (a tribe of the former Cavares Confederation). (See A Guide to the Ancient World, page 57)

Many of the books place the Tricastini at present day St. Paul Trois Chateaux, cutting off the portion of the confluence of the Aygues and Rhone Rivers from their territory. Certainly, tribal migrations have occurred during Roman times, but if some historians point to church diocese as tribal limits, then land taken from the tribes must be in play, too.

Vasio Vocontiorum (present-day Vaison la Romaine), 13 miles northeast from Arausio, was the capital of the Vocontii (See A Guide to the Ancient World, page 681).

Both those places were well-populated and well-cultivated in its time, and Orange sits on the Aygues River. However, just south of the Aygues, about a third of the way between Avignon and Orange (10km from Avignon and 20km from Orange), runs the Ouveze River. The Ouveze, which also counts the Nesque River as a feeder river, enters the Rhone at an angle similar to the Aygues, is the most southernmost major watercourse that can still form the triangle, and claims the Baronnies Mountains as the inaccessible mountainous border.

The confluence is about 75km in distance from Arles following the twists and turns of the Rhone. The 105km mark would place the Island roughly at Orange and the Aygues. But if Orange is already Tricastini territory, then Hannibal could not "turn left to the territory of the Triscatini, proceeding thence past the borders of the Vocontii." Brancus was evidently not part of the Tricastini tribe. Indeed, Livius refers to the entire matter as settling the "business of the Allobroges." [Livius, XXXI, 31] Other authors comment on a scattered number of tribal groups south of the main land claimed by the Allobroges, typically north of the Isere River.

Based on that statement, it appears Hannibal had not yet reached the Tricastini. The 75km march is almost 50% faster than the average, which is because Hannibal is trying to put distance between his army and the Romans.

One wonders why you'd call a place "The Island." It must have been a particular reference point, as there is no corresponding "Island" in the Nile Delta, and according to Polybios, the two are supposedly similar in nature. Perhaps it is a 300-foot hill towering over a plain at the confluence of a couple rivers? As one of the centers of the Cavares Confederation, it would have been one of the dominant towns in the area. Entering this delta area means to enter its jurisdiction, and the Ouveze River would have been a boundary point of note.

The Island may very well have been Arausio itself, considering the way the land rises from the delta, or the narrow area between the Ouveze and Aygues Rivers. And it is within the distance of march for an army to reach in four days.

Here, at the Island, Hannibal intervened in the tribal dispute over leadership, ultimately backing the winning party of Brancus, who reciprocated by re-equipping the Carthaginian army. The territory of Brancus exists somewhere between the Ouveze and Aygues Rivers. Hannibal felt safe with two rivers in between the Romans and the Carthaginians--the Durance and the Ouveze--as well as the strength of his new-found friend.

From the Island, Hannibal "turned left" or "veered left" (depending on the translator) and marched by Arausio. He evidently did not have permission to go through Vocontii territory, for he proceeded past their borders to the Tricorii. As the Vocontii were centered at Vasio Vocontiorum (present-day Vaison la Romaine), 13 miles northeast from Arausio (Orange), Hannibal had to detour around the territory instead of making a straight run at the Alps.

He initially went north along the Rhone. It is tempting to branch off to travel along the "river," as Polybios notes, and follow the Aygues. Hannibal must be starting to worry about crossing the Alps. He had just been issued winter clothing by Brancus. He knows the Alps are higher than the Pyrenees. His Boii guides have said passage is difficult, but not impossible. Time is slipping by and his detour north along the Rhone--for he had failed to slip by the fast-marching Romans--threw his already delayed march further behind schedule. He's got to be thinking about how he's going to get 50,000+ troops across a difficult pass.

Brancus is guarding his rear, so he has a good source of information about tribal boundaries. Hannibal is trying to thread the needle between the Vocontii to the south and the larger Allobroges to the north. Besides, Brancus is new to the throne. He probably--and this is reasonable speculation--does not want to antagonize neighbors within days of being declared head of the tribe. The Vocontii, though not an enemy to the Carthaginians, are no friends, either. And while they may not be powerful, they are not pushovers. Hannibal must detour around their land. That's why it is more credible for the Carthaginian Army to "avoid the most direct route" and march "left" up the Rhone instead of the Aygues. [Livius XXI, 31]

Polybios notes the distance covered between the Island and the Ascent of the Alps is 140km in 10 days. Livius notes the Carthaginians have to cross a hazardous stream, the Druentia, after which they turn to the Alps over fairly open country. Polybios mentions no stream or river, but does mention that during this phase the army marched on the river banks.

Hannibal Crosses the Alps A Route Examined and a Proposed Alternate Route

-

Introduction

The Sources

Hannibal's March: Polybios and Livy

Polybios vs. Livy: Debate Over Details

A New Route Proposed: Begin at the End

A New Route Proposed: Start at the Beginning

A New Route Proposed: Where is the Druentia?

A New Route Proposed: The Pass in the Alps

Aftermath, Conclusion, and Bibliography

Back to Strategikon Vol. 2 No. 1 Table of Contents

Back to Strategikon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by NMPI

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com