The summarudis (referee or marshal) in traditional garb would separate the gladiators, keeping them apart his rudis (long wooden stick until the editor singled commence.. His assistant (secunda rudis) would stand across from him slightly behind a fighter (see fig. 3). If the gladiator forgot himself and went for the summarudis, the secundus was to protect him by grabbing the fighter.

The summarudis (referee or marshal) in traditional garb would separate the gladiators, keeping them apart his rudis (long wooden stick until the editor singled commence.. His assistant (secunda rudis) would stand across from him slightly behind a fighter (see fig. 3). If the gladiator forgot himself and went for the summarudis, the secundus was to protect him by grabbing the fighter.

Figure 4: Pompeian tomb relief showing gladiator receiving refreshment during a diludium. Circa 40 CE

The fight was formalized fencing that, according to the dictata leges pugnandi, observed strict rules. Most details are unknown. Yet it is interesting to note that the Society of Creative Anachronism use the same conventions mentioned by the ancient authors, at their own Lists (Ritualized duels for political offices) as for the ancient Gladiators. If there was blatant cheating or if the fighter lost protection due to faulty equipment the summa rudis would suspend the proceedings, order the combatants back to their starting positions. The SCA does the same. Some fights (lineae albae) chalk lines were placed on the ground the gladiators remaining with in them while fighting. To be driven outside was to lose. The SCA uses rope but maintains the same principle.

If the combat ran a long time, with both fighters becoming exhausted the summa rudis might order a diludium. There is detail showing such a break on a tomb relief (see fig. 4). Wounds could be treated, but the crowd preferred to watch bleeding, screaming "Habet!" when fighters first bled.

Often if low-class combatants showed indiscipline or a lack of attacking spirit the summa rudis was unmerciful in use of his stick. When the sparing was confined between amateurs condemned to death the secundus were sent in with whips, or red-hot irons heated on the sand in tripod braziers using charcoal. These were applied to the buttocks to encourage the poor wench to close and kill or be killed.

Well-schooled gladiators would use differing techniques against different opponents, skill that was appreciated by their experienced audience. Techniques such as lunging, parrying and feinting were based on protecting the body as the limbs usually had armor. The different types swords were called short swords, and were modeled after the Roman military weapon the Gladius Hispanicus.

Fighters depended on their shield, (if square, scutum, or if round cilpis, hoplon) to protect the body. The first order of business was to eliminate the shield.

This could be done by hacking it to pieces, or cutting the arm holding it. The sica of the Thrax (thracian style) was curved to allow a skilled fighter to reach around the edge of the scutum and slice the tendons of the arm forcing him to drop the shield. Gladiator shields were lighter then normal Roman equipment, so that repeated blows would eventually wreck it. Such a shield was recovered at Dura Europos in Syria. The shield is covered in popular gladiator motifs and is built of composite, laminated strips of light wood.

The swordsman would attack and defend with his shield, forcing his enemy back with its mass, then feigning an attack on a area to provoke a defensive reaction, then as the defender moved to protect the exposed area, thrust at an unprotected area. Excellent fighters could parry such a thrust with their sword without moving their shield, keeping protected and still defeating the enemy's attack.

Based on the description of the practice butts, gladiators used more thrusts then slices. A slice could be directed at a head, but to do so, with such a short sword, this would force the gladiator to open himself to an attack. Cagy opponents might leave a shot at the head open to see if a less experienced fighter would take advantage.

No Time Limit

At the men tired, openings would appear and the fighters would start to suffer damage. Usually this was in blood loss, though sometimes a lucky blow might disable a fighter. Since there was no time limit to fights; they continued until a victor was decided.

If two gladiators had fought for a very long time with great courage, and neither gained the victory the crowd, if they were feeling good, would demand the editor to administer stantes missi. This means "dismissed standing" and both fighters would depart through the gate of life. The fight would be scored a draw, and bets returned.

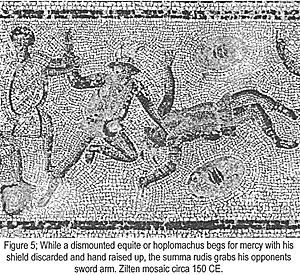

Usually though because the opponent was so weak from blood loss or physical exhaustion, he could no longer continue. When this happened the defeated fighter dropped his shield to the ground, or lowered his weapon and raised one hand. We see this on the Zliten mosaic (see fig.5). We also see the summa rudis coming between the fighters and blocking the conqueror or grabbing his sword arm keeping him from making any further attack on his now defenseless opponent, as also shown in figure 2.

The contests was far from over. The loser now submitted to the decision of his fate to the munus editor, but convention demanded the editor consult the audience, since as a general rule he went along with the feeling of the audience. If the fighter was a favorite or fought with courage and followed the rules of combat, surrendering when the situation was completely insurmountable, he gained the sympathy of the crowd.

The crowd in turn would show the editor their feelings who by waving the hems of their togas or cloaks or by crying "mercy" (missum) or mitte "send him back." Accepting the mob's decision, the editor gave a signal to the summa rudis to discharge the defeated gladiator from the arena alive.

If the fickle audience was bored, or unhappy with the defeated fighter's showing, or they lost money on the bout, they would demand his death by showing pollice verso (thumbs up), opposite to the modern illusion that thumbs down meant death, (thanks to the novel Spartacus, adapted from the painting by Jean-Leon Gerome showing thumbs downtrend), often also crying out 'iugula!' (that is: kill him).

Figure 5: While a dismounted equite or hoplomachus begs for mercy with his

shield discarded and hand raised up, the summa rudis grabs his opponents

sword arm. Zilten mosaic circa 150 CE.

Figure 5: While a dismounted equite or hoplomachus begs for mercy with his

shield discarded and hand raised up, the summa rudis grabs his opponents

sword arm. Zilten mosaic circa 150 CE.

It was assumed that in death the loser would give an example of plum virtutis, manly virtue, by kneeling before the victor, arms clasped behind his back or, embracing the legs of the gladiator standing over him, offering himself to the final thrust. The kill stroke was a thrust, not decapitation. While we hear of Celtic gladiators doing this in the provinces since head taking was a traditional warrior ritual, the Romans and Samnites did not.

Helmets were retained keeping his face obscured. It is believed the use of visored helmets made the wearer an unknown fighting machine, so aggression against him could take place with no inhibitions.

I disagree with this, the visors were there to protect from thrusts, a crippling, often fatal blow, and one which would end a bout fairly quickly, thus giving no sport to the spectators and to obscure the eyes of the fighter's eye movements as well, so no "tells" could be seen. The fighters with no armor and helmets were condemned prisoners that could be used up fairly quickly, but man to man fighting by trained gladiators was a sizable investment in time and money, and the longer the outcome was delayed the better was the chance that both fighters would live.

The moment when the loser took the thrust (ferrum recipere) was usually marked by the cry 'habet!' (he has it!), an exclamation that also was used when a fighter drew first blood. (It assumed this was to tell the bookies who had won so they had to pay depending on the bet.)

When he was dead he was taken away through the gates of death on a covered stretcher, (examples of stretchers ready to be used are shown on the Zliten mosaic), and placed in the mortuary, (sporliarium) where his throat was cut, usually with witnesses, to prevent any rumors of colluded contests were both fighters survived. After this he would be undressed, washed and prepared for interment.

While modern writers talk about a man dressed like the god of the underworld, Charon, who brained fallen gladiators, then dragged them out by their heels with iron hooks, I must say we have no proof. The only person that mentions this is the anti-munus writer Tertullian (AD 156-220). He was Christian, who loved to focus on the connections between Roman Religio and the evil spectacles to scare his readers by saying that damnation awaited such an audience.

Because he was anti-religious, based on the lack of other mention by writers and no pictorial evidence, I am inclined to believe it was not a normal practice. We know that the noxii, criminals executed in the arena, were removed by hooks, thus showing them no dignatis. It is possible that Tertullian heard about a restaged myth about Charon and noxii and assumed these were gladiators. Gladiators were shown dignatis in death. It was expected. Gladiators desired proper funerals and based on the numerous number of funerary inscriptions that endure to this day, this was carried out.

Those who left through the gates of life and were wounded were given the best possible medical treatment. Usually this meant cauterizing cut wounds with a hot iron, and setting broken limbs. There was no cure for deep stomach wounds; peritonitis would eventually kill the fighter.

While Romans did not understand germs, they had an appreciation for infection, which they believed caused an imbalance by the bad humours mixing with the good. This imbalance caused disease so holes in the body must be closed to prevent mixing.. By cauterizing, the heat killed the remaining germs, those which had not eliminated by the blood flow, though the Romans believed it was the closing of the wound that was the cure, not scorching the flesh.

Gladiators had to be taken care of since a experienced swordsman had substantial business value, and the loss of an asset was something the lanista and the editor wanted to avoid, the lanista, since an experienced fighter was hard to replace, and editor because his basic agreement was to pay the trainer a much higher figure if the fighter was dead or even permanently disabled. Such a fee would twice perhaps three times the price of the fighter's rental.

Post Combat

Now the victor would honored. In a large munus all the victors were honored collectively, a small one, often individually. Depending on the size of the arena, the ritual varied but usually the victor mounted the editor's platform to receive his reward. These frequently included a palm branch (palma, sign of victory) and a praemium or sum of money, amount varying by seniority. If there had been an exceptional consummation of the fight, and the fighter was senior enough he might also be awarded the aspired laurel wreath (corona) and other gifts. Well wishers also threw money and tokens into the arena for the fighter. The practice is still carried out in the in the tossing of flowers into the bullfighting ring. The money became the fighter's own property, even if he was a slave. Roman law had made a special distinction allowing a slave to gain money in this instance.

A very special outcome for a superb fight, frequently after a senior gladiator had spent a weekend in daily victorious fights, was the wooden sword (rudis). It was a practice weapon handed to the victor by the Emperor or his family member. This was the recognized stipulation that the fighter was now released from his obligation to his lanista to fight in the arena and was a freeman.

Such an honor, though, was a financial disaster for the editor of the immus, for the law stated now he had to purchase an equally good gladiator as a replacement. He could only hope that the Imperial family would cover the cost. In good times that often happened.

After receiving his prizes and congratulations, he was expected to run once around the sand so he might receive the acclamation of the crowd. He was to wave his palm frond, while running, to encourage more cheers and tokens of favor from the spectators (See fig. 6).

At that point I imagine that like most victorious athletes our fighter felt he was at the pinnacle of his success. (The closest I have ever seen something similar today was when Cal Ripkin Jr. shook the hands of people on the lower level of Camden Yards after breaking Lou Gehrig's streak. While Ripkin jogged around the stadium's track waving, and shaking hands with the spectators, I was transported back to ancient Rome and the lap of victory by the munus winner.)

More History of the Munus Part 2 Gladiatorial Contests

-

Executing the Munus

The Preparation

Conduct of the Gladiatorial Contests

The Fight and Post Combat

Gladiators and Their Future

More History of the Munus Part 1 Gladiatorial Contests

-

Origins

The First Contests in Rome

The Games as a Political Tool

The Demise of the Munus

Ave Imperator: Gladiator Game Rules

Ave Imperator: Record Sheet

Re-enactor: Maximus the Lanista

Back to Strategikon Vol. 1 No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Strategikon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by NMPI

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com