Striking at Britain Indirectly Through an

Napoleon's daring expedition to Egypt grew out of France's inability to strike a direct blow across the English Channel at the only nation still at war with France in 1798, Great Britain.

Napoleon's daring expedition to Egypt grew out of France's inability to strike a direct blow across the English Channel at the only nation still at war with France in 1798, Great Britain.

Organized primarily at the port of Toulon, 29-year-old General Bonaparte's massive armada consisted of 35,000 soldiers, 13,000 sailors, and hundreds of ships, including 72 military vessels. Included in the expedition were 167 scholars and scientists, known as the savants, whose mission was to help modernize Egypt as well as explore and chronicle the lost Egypt of antiquity. Napoleon dreamed of building a great colony, of digging a canal at Suez, and of leading, much like Alexander the Great, a campaign to Persia and India.

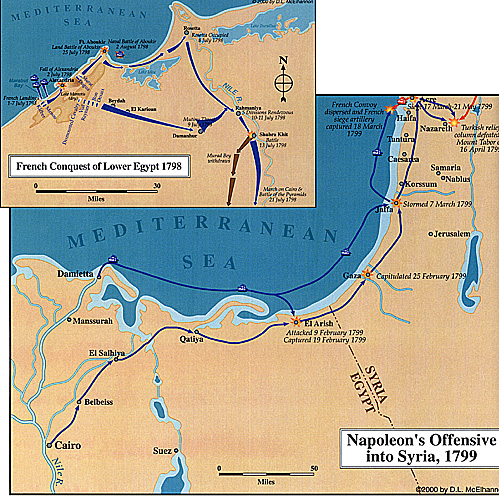

Having seized Malta along the way on 10 June 1798, Napoleon's fleet avoided the British warships chasing it, landed in Egypt, and then captured Alexandria on 2 July. Advancing through the desert in sweltering heat, Napoleon's army routed the Mameluke army defending Cairo at the Battle of the Pyramids on 21 July.

The Mamelukes were fierce warriors who had ruled Egypt for their Ottoman masters since the 13th century. Individually fearless, the resplendent Mameluke medieval cavalry was no match for French firearms, artillery, and disciplined tactics.

The Mamelukes were fierce warriors who had ruled Egypt for their Ottoman masters since the 13th century. Individually fearless, the resplendent Mameluke medieval cavalry was no match for French firearms, artillery, and disciplined tactics.

Napoleon's ambitions received a crushing blow when news arrived of British Admiral Horatio Nelson's annihilating victory over the poorly deployed French fleet on 1-2 August at Aboukir Bay. Now cut off from France, Bonaparte, in typical fashion, resolved to strike a hard blow at his enemies in Syria before they could receive further reinforcements from the Ottoman Sultan. Napoleon's invasion of Syria in early 1799, a savage campaign fraught with hardships that included an outbreak of the plague in Jaffa and the subsequently controversial execution of its defeated garrison, ultimately stalled in front of the great fortress of Acre. Defeated, Napoleon retreated back to Egypt in time to slaughter a Turkish landing at Aboukir on 25 July.

When news arrived that the French Republic had been defeated in Italy and Germany in his absence, Napoleon resolved to return home. In fact, orders were sent recalling him, but because he left before those orders arrived, he would never escape charges that he abandoned his army.

Ultimately, due to the heroics of the British Royal Navy and stubborn opposition at Acre, the expedition to Egypt proved to be a catastrophe that was ended by a British-Ottoman campaign in 1801. Yet little blame attached to Bonaparte. His battlefield victories were well-publicized and increased his acclaim. The exotic setting, with its biblical scenes, captured the French imagination and added to Napoleon's mystique. Moreover, the scientific accomplishments associated with the venture proved enduring. Napoleon's arrival in Paris on 14 October 1799, much to the disappointment of his rival General Jean-Baptiste Jules Bernadotte, was met with great interest and enthusiasm, Egypt-mania having already taken hold in France.

The Institute of Egypt

Napoleon intended that the French invasion of Egypt should be more than just a military venture and he brought with his army approximately 167 civilian scholars, scientists, architects, and engineers. Their purpose was to investigate every aspect of Egyptian society, culture, geography, history, politics, commerce, agriculture, and manufacturing in order to prepare Egypt for colonization. Napoleon formally created The Institute of Egypt, modeled after the French National Institute, as a learned body to organize the scholars' research. The Institute included luminaries like art historian Dominique Vivant Denon, mineralogist Deodat Dolomieu, zoologist Geoffry Saint-Hilaire, chemist Claude-Louis Berthollet, and mathematician Gaspard Monge. The final result of their work was the monumental, lavishly illustrated Description of Egypt, one of the first pieces of modern Egyptology.

Napoleon intended that the French invasion of Egypt should be more than just a military venture and he brought with his army approximately 167 civilian scholars, scientists, architects, and engineers. Their purpose was to investigate every aspect of Egyptian society, culture, geography, history, politics, commerce, agriculture, and manufacturing in order to prepare Egypt for colonization. Napoleon formally created The Institute of Egypt, modeled after the French National Institute, as a learned body to organize the scholars' research. The Institute included luminaries like art historian Dominique Vivant Denon, mineralogist Deodat Dolomieu, zoologist Geoffry Saint-Hilaire, chemist Claude-Louis Berthollet, and mathematician Gaspard Monge. The final result of their work was the monumental, lavishly illustrated Description of Egypt, one of the first pieces of modern Egyptology.

The Rosetta Stone

The most famous discovery made during the French occupation of Egypt was entirely accidental. A military engineer working on fortifications near Al-Rachid (called Rosetta by Europeans) found the artifact and fortunately recognized its significance. The stone was inscribed in hieroglyphs, demotic characters, and Greek. Scholars immediately recognized that it held the key to understanding the lost language of the ancient Egyptians. The British claimed the famous stone as a trophy of war in 1801, and moved it to the British Museum, where it remains. Deciphering the hieroglyphs took approximately twenty years. The English physicist Thomas Young made substantial progress on the inscription, but the French linguist Jean-Francois Champollion recognized the phonetic values of the symbols. Learning the ancient language laid the foundation for the profession of Egyptology.

More Napoleon: Introductory Guide

-

Introduction

Prejudice and Pride

Napoleon in Military School

The Young Artillerist's Double Life

Revolution & Opportunity

Women's Fashion During the Revolution

The Siege of Toulon

Napoleon & Josephine

Women's Fashion during the Directory

Fame & Glory: Italy

Fame & Glory: Egypt

Saviour or Usurper

Battle of Marengo

Civil Achievments

Enlightened Despot or Tyrant

Napoleon's Siblings

The Dawn of Gastronomy

Haydn and Beethoven

Women's Fashion during the Empire

Napoleon's Other Women

The Mashalate and Imperial Eagle

History's Greatest General?

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #17

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Napoleon LLC.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

Order Napoleon magazine direct