As counter-revolution broke out in places like Marseilles and Lyon, Napoleon's artillery regiment found itself in the midst of civil war, on occasion helping the local revolutionary governments restore order. At Avignon and Marseilles, Napoleon, who favored order, watched horrified at the bloody reprisals inflicted on the royalist sympathizers by Jacobin deputies like Joseph Fouche (who would become Napoleon's future, ruthless chief of police). It was at this time that politicians in Paris noticed Buonaparte for his pro-Jacobin pamphlet, Le Souper de Beaucaire, a dialogue between a soldier and a merchant in which the soldier persuasively argues for an end to the civil war and submission to the central government.

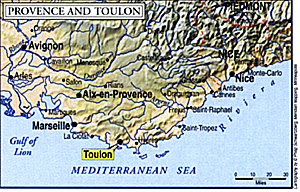

Napoleon's pressing ambition at this time was to fight against a foreign enemy, not fellow Frenchmen. His first big opportunity came when fellow Corsican Salicetti, a Deputy on Mission with the French army besieging Toulon, gave him a command fighting the British, Piedmontese, and Spanish who had seized this crucial port through the help of the local royalists.

At the siege of Toulon (17 September to 18 December 1793) Napoleon initially served under the incompetent General Carteaux. However, through appeals to Salicetti and superiors in Paris, he received command of the artillery for the Republican forces. When a capable commander, General Dugommier, finally arrived on 16 November, Captain Buonaparte (he would sign his name this way until 1796) was allowed to execute his plan.

At the siege of Toulon (17 September to 18 December 1793) Napoleon initially served under the incompetent General Carteaux. However, through appeals to Salicetti and superiors in Paris, he received command of the artillery for the Republican forces. When a capable commander, General Dugommier, finally arrived on 16 November, Captain Buonaparte (he would sign his name this way until 1796) was allowed to execute his plan.

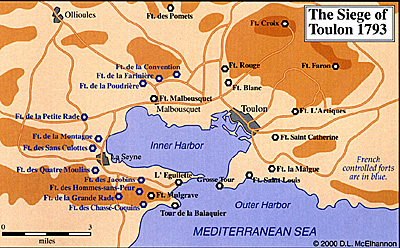

The key to Toulon, in Napoleon's view, was the heights crowned by Fort Mulgrave, known as "Little Gibraltar" to the French. By capturing this prominent position, the French could then seize further positions where the artillery could fire a devastating bombardment on the British fleet below.

Buonaparte went to work with extraordinary energy, requisitioning cannon and supplies, training new artillerists, constructing earthworks, and, overall, applying his knowledge of the complex science of siege-work. When a British sortie succeeded in overrunning and spiking seven siege guns, Napoleon personally led a successful counterattack -- the British commander, General O'Hara, was captured in the action.

Finally, after massive preparations by Napoleon's artillery, the Republicans stormed Fort Mulgrave and Point l'Eguilette on 17 December, with Buonaparte taking a bayonet wound to the thigh while leading the attack. On the following day, British Admiral Hood recognized the inevitable and began operations to evacuate Toulon, including blowing up the arsenal. Chaos ensued as Hood's forces set fire to many French ships in the harbor, and panicked citizens tried to escape on royal navy vessels.

Finally, after massive preparations by Napoleon's artillery, the Republicans stormed Fort Mulgrave and Point l'Eguilette on 17 December, with Buonaparte taking a bayonet wound to the thigh while leading the attack. On the following day, British Admiral Hood recognized the inevitable and began operations to evacuate Toulon, including blowing up the arsenal. Chaos ensued as Hood's forces set fire to many French ships in the harbor, and panicked citizens tried to escape on royal navy vessels.

Diorama built by Rod Langton has 150 ships and buildings in 1/1200 scale (1 inch equals 100 feet) on a 4 x 8 foot table (Courtesy of Rod Langton)

On the morning of 19 December, Republican forces entered Toulon. The triumph quickly turned into reprisals, as Jacobin deputies supervised the retribution. On 20 December, about five hundred collaborators were shot. The wounded Buonaparte disapproved of the slaughter, although later anti-Buonaparte propagandists would fancifully claim that Napoleon himself directed artillery fire into a mass of victims.

As a reward for his excellent service, on 22 December, Captain Buonaparte was promoted to Brigadier General at the age of twenty-four.

As a reward for his excellent service, on 22 December, Captain Buonaparte was promoted to Brigadier General at the age of twenty-four.

Italy and Then Arrest

While the Fates smiled on Napoleon by providing him with his first major opportunity at Toulon, his postings over the next 18 months paved the way to his famous Italian campaign.

After a brief tour of duty inspecting coastal defenses, Napoleon became artillery commander for the Army of Italy. As at Toulon, Napoleon formulated a decisive plan to resolve the strategic impasse in that region. However, despite some initial successes, the French hesitated to advance further inland without approval from the government in Paris. In the meantime, General Buonaparte carried out a daring behind the lines reconnaissance of the critical port of Genoa.

Not long after Napoleon's spy mission, Robespierre's dictatorship was overthrown in August 1794. The rise of the Thermidoreans initially created serious problems for him. His Corsican patron Salicetti, in an effort to save himself, accused Buonaparte of treason. Napoleon was arrested, his papers seized, and he was stripped of his new rank. Although he was ultimately cleared after a couple of weeks, Buonaparte narrowly avoided being executed in the backlash against the radical Jacobins.

Napoleon then returned to his command in Italy, providing the impetus for another short offensive which resulted in a minor French victory. The commander of the Army of Italy, the cautious General Dumerbion, called a halt to the offensive, and the French held their advanced positions along the Mediterranean coast, within striking distance of Genoa. Shortly thereafter, Napoleon was recalled from Italy to help command an expedition to Corsica. However, the British navy foiled the plan, and General Buonaparte found himself without a command.

The Ministry of War, in a rather strange bit of bureaucratic nonsense, transferred Napoleon to the infantry (an insult to him) and ordered him to the civil war in the Vendee. Disgusted, he placed himself on sick leave. Further arguments with the War Ministry led Napoleon to resign his command, but in August he was recalled to the Topographical Bureau to assist the Army of Italy again. His planning resulted in another successful offensive, but Napoleon was fired again without much cause.

The Whiff of Grapeshot

The Whiff of Grapeshot

With his career in serious jeopardy, General Buonaparte languished in Paris in great despair, his personal finances in severe trouble. He was so depressed that he even mused upon suicide. However, with more political upheaval brewing in Paris, fortune once more smiled upon Napoleon.

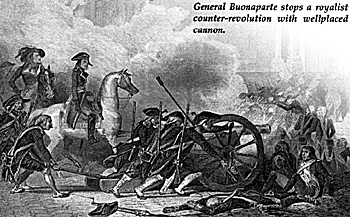

The newly constituted Directory found itself in deep political trouble, having had essentially to void recent elections in order to retain power. The royalists, who were thwarted politically, organized a counter-revolution: National Guardsmen planned to march on the Tuileries and stage a coup d'etat. Paul Barras, the Director appointed to command the army in this crisis, turned to the unemployed Buonaparte for help. Napoleon, remembering what he had seen in 1793, recognized that the issue could be decided by cannon, and he sent his subordinate and future brother-in-law, Joachim Murat, on a race to secure the artillery before the National Guard could get them.

The mission was a success, and Napoleon deployed his guns covering the main approaches. When the mass of insurgents approached his guns from the area of the Church of St. Roch on 5 October 1795, Napoleon ordered a devastating series of salvos. Although skirmishing went on for some time, the affair was already decided, known forever to history as "The Whiff of Grapeshot." General Buonaparte had saved the Directory and the Revolution, and he would be rewarded with command of the Army of Italy.

More Napoleon: Introductory Guide

-

Introduction

Prejudice and Pride

Napoleon in Military School

The Young Artillerist's Double Life

Revolution & Opportunity

Women's Fashion During the Revolution

The Siege of Toulon

Napoleon & Josephine

Women's Fashion during the Directory

Fame & Glory: Italy

Fame & Glory: Egypt

Saviour or Usurper

Battle of Marengo

Civil Achievments

Enlightened Despot or Tyrant

Napoleon's Siblings

The Dawn of Gastronomy

Haydn and Beethoven

Women's Fashion during the Empire

Napoleon's Other Women

The Mashalate and Imperial Eagle

History's Greatest General?

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #17

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Napoleon LLC.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

Order Napoleon magazine direct