Few could have foreseen that the French Army of Italy -- a tattered force of ill-equipped, underfed, and unpaid men, led by a lovestruck, twenty-six-year-old general -- would, in the spring of 1796, set out across the mountains of Italy and launch a campaign that would astonish the world.

Few could have foreseen that the French Army of Italy -- a tattered force of ill-equipped, underfed, and unpaid men, led by a lovestruck, twenty-six-year-old general -- would, in the spring of 1796, set out across the mountains of Italy and launch a campaign that would astonish the world.

The first priority of General Bonaparte (as he now spelled his name), even before he set about restoring the morale of his troops, was to gain the respect of his subordinates, men senior to Napoleon in age and military experience. Disgusted by what they perceived as a political appointment, the generals of the Army of Italy, led by Pierre Augereau and Andre Massena, determined not to obey this young upstart, sarcastically dubbed "General Vendemiaire" for his suppression of royalist counter-revolutionaries in the "Whiff of Grapeshot" incident in Paris (p.34). Napoleon's first council of war was a tense confrontation. According to one apocryphal version of this event, none of the generals stood or removed their hats when he entered the meeting. Napoleon stood above them and left his hat on, glaring at the disrespectful officers until, rather sheepishly, they removed their hats. Then Napoleon launched into a detailed plan for the upcoming campaign that both impressed and intimidated his subordinates. "I can't understand why," commented the tough veteran Augereau, "but this little bastard frightens me."

Having been granted the tenuous respect of his generals, Bonaparte now moved to stir the spirit of his men: "Soldiers! You are hungry and naked; the government owes you much but can give you nothing. The patience and courage that you have displayed among these rocks are admirable; but they bring you no glory -- not a glimmer falls upon you. I will lead you into the most fertile plains on earth. Rich provinces, opulent towns, all shall be at your disposal; there you will find honor, glory and riches. Soldiers of Italy! Will you be lacking in courage or endurance?"

Having been granted the tenuous respect of his generals, Bonaparte now moved to stir the spirit of his men: "Soldiers! You are hungry and naked; the government owes you much but can give you nothing. The patience and courage that you have displayed among these rocks are admirable; but they bring you no glory -- not a glimmer falls upon you. I will lead you into the most fertile plains on earth. Rich provinces, opulent towns, all shall be at your disposal; there you will find honor, glory and riches. Soldiers of Italy! Will you be lacking in courage or endurance?"

Napoleon knew that mere rhetoric would not be enough -- he brought with him money and arranged for supplies to be delivered. His soldiers would respond with enthusiasm and courage to this young general who looked after their most pressing needs.

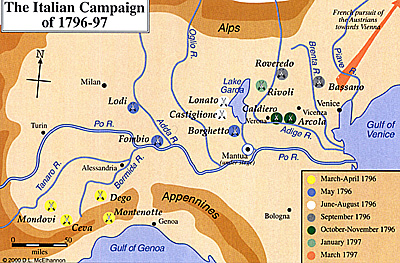

Napoleon's genius as a soldier was quickly evident. He fused maneuver and battle in a manner that befuddled his slower moving foes. Finding the weak point between the Austrian and Piedmontese armies, he massed his men to rupture and sever the enemy dispositions in a method that he would repeat throughout his career. Beginning with his first battle as a commanding general (Montenotte), Napoleon and his men attacked in a relentlessness series of engagements that separated the Austrians from their allies and knocked Piedmont out of the war at the battle of Mondovi. Napoleon personally negotiated the resulting Armistice of Cherasco on 28 April 1796.

The Army of Italy now turned to pursue the Austrian army up the Po River valley. The prize before them was the magnificent city of Milan. Along the way, an attempt to cut off the retreating Austrians resulted in the celebrated charge over the bridge of Lodi, where the French stormed through fierce cannon fire to cross the Adda River and scattered the Austrian rearguard. It was a spectacular and dramatic victory, the sort that inspires paintings and stirs the hearts of soldiers. Napoleon himself said that it was not until Lodi that "I felt that I could abandon myself to the most brilliant of dreams - his star of destiny."

On 13 May Napoleon and his army entered Milan. In his wake, the representatives of the Revolutionary government began the process of making war pay for war, and the Directory started a systematic plundering of Italian resources to rescue France from its enormous financial difficulties.

However, the strategic key to Northern Italy, the great fortress city of Mantua, remained in enemy hands, held by the remainder of General Johann Peter Beaulieu's Austrian army. On 3 June, the French placed the great fortress under siege. Napoleon soon found himself in a difficult position. His 43,000 men had bottled up 13,000 Austrians in Mantua, but now they had to contend with a relief force of 50,000 coming south from the Tyrol under General Dagobert Wurmser. A lesser general might have retreated to Milan. Napoleon attacked, taking advantage of Wurmser's vulnerability as he divided his forces to converge on the French. First at Lonato, then in the famous battle of Castiglione on 5 August, Napoleon outfought Wurmser and drove him back north toward the Tyrol. Forced temporarily to raise the siege of Mantua, Napoleon had concentrated his men and won an audacious victory over superior forces.

By slipping back southward, Wurmser made a second effort to relieve Mantua. Napoleon, rather than race back to head off Wurmser's advance, followed behind the Austrians to pounce from the rear. Napoleon won another brilliant victory at Bassano on 8 September, ultimately chasing the pitiful remnants of Wurmser's men into the fortress of Mantua, where they would be subjected to appalling overcrowding and the ravages of malaria.

The Austrians, now with 22,000 men trapped in Mantua, sent yet another relief force into Italy. General Josef Alvintzy, with 46,000 men, sorely pressed the Army of Italy. Napoleon, outnumbered by half, launched a series of desperate engagements, including one serious defeat at Caldiero, that pushed his exhausted soldiers near to the breaking point. At the harrowing Battle of Arcola, Napoleon was nearly killed while leading an unsuccessful charge across a bridge into galling enemy fire. By means of a ruse, Bonaparte used his cavalry -- and their trumpets -- to bluff the Austrians into believing they had been outflanked. Arcola was a close-run victory to be sure.

The Austrians, now with 22,000 men trapped in Mantua, sent yet another relief force into Italy. General Josef Alvintzy, with 46,000 men, sorely pressed the Army of Italy. Napoleon, outnumbered by half, launched a series of desperate engagements, including one serious defeat at Caldiero, that pushed his exhausted soldiers near to the breaking point. At the harrowing Battle of Arcola, Napoleon was nearly killed while leading an unsuccessful charge across a bridge into galling enemy fire. By means of a ruse, Bonaparte used his cavalry -- and their trumpets -- to bluff the Austrians into believing they had been outflanked. Arcola was a close-run victory to be sure.

At Rivoli on 15 January 1797, Napoleon defeated Alvintzy again, and this marked Austria's last serious effort to retake northern Italy. On 2 February 1797, the 15,000 survivors in Mantua surrendered. Napoleon soon resumed his advance, marching on Vienna in the early spring. Faced with this threat the Austrians began negotiations, signing the Preliminaries of Leoben on 18 April and the Peace of Campo Formio on 17 October. Among the terms, Austria ceded Belgium and northern Italy to France, and, by secret clause, also conceded the left bank of the Rhine.

Having defeated four separate armies and three major relief attempts directed at Mantua in just twelve months, Napoleon's success dazzled Europe. A French army of 40,000 men, considered to be operating in a secondary theater, had ultimately brought Austria to its knees. The acquisition of fertile lands and the taxation of wealthy Italian cities -- including 30 million francs from the Papacy -- restored the treasury of the Directory and enhanced the Republic's prestige. The young general who achieved this became France's foremost hero.

More Napoleon: Introductory Guide

-

Introduction

Prejudice and Pride

Napoleon in Military School

The Young Artillerist's Double Life

Revolution & Opportunity

Women's Fashion During the Revolution

The Siege of Toulon

Napoleon & Josephine

Women's Fashion during the Directory

Fame & Glory: Italy

Fame & Glory: Egypt

Saviour or Usurper

Battle of Marengo

Civil Achievments

Enlightened Despot or Tyrant

Napoleon's Siblings

The Dawn of Gastronomy

Haydn and Beethoven

Women's Fashion during the Empire

Napoleon's Other Women

The Mashalate and Imperial Eagle

History's Greatest General?

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #17

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Napoleon LLC.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

Order Napoleon magazine direct