Without question, the French Revolution marks one of the great turning points in western history. This cataclysm not only ushered in the modern world, but also contained within its various strands and convolutions a veritable overture of the political movements that would fight for ideological mastery in the centuries to come.

As the Revolution degenerated from idealism to disillusionment, and disintegrated into chaos as a consequence of the Revolution's failure to derive an effective form of government, one man arose to take power and restore order in France. Ever since that fateful day in 1799 historical debate has ranged from those who feel Napoleon Bonaparte saved the French Revolution to those who feel he betrayed it. Was he a cynical opportunist or a true child of the Revolution? The following pages outline the key events of the French Revolution as they unfolded.

Louis XVI recognizes that the state is bankrupt

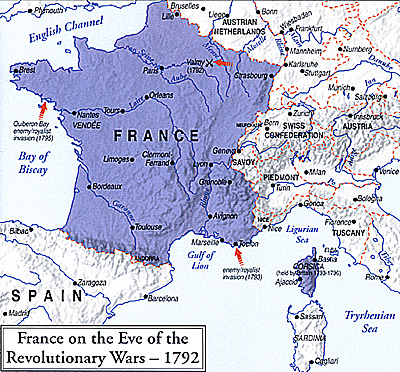

Although the economy of France was strong and growing, the government of Louis XVI was bankrupt, due in part to its costly support of the American Revolution (1775-1783) as well as to its archaic and inefficient administrative methods. Further destabilizing the ancien regime were great inequities of wealth. Peasants did not benefit from the long-term growth in France's prosperity, but were greatly afflicted by the short-term economic crises caused by poor harvests, swings of unemployment brought about by changes in manufacturing and trade, and the occasional sudden rises in the price of bread -- the latter which precipitated escalating outbursts of rioting. The peasants also bore an unfair tax burden as the aristocracy increased its tax privileges.

Louis XVI calls the Estates-General

Louis XVI calls the Estates-General

Although an absolute monarch in name, the ineffectual Louis XVI was in reality powerless to raise money without receiving the consent of his nobility, whose increasing unwillingness to cooperate without royal concessions culminated in the revolt nobilaire of 1787-1788. Therefore, near the end of 1788, the King took the unusual step of convening the Estates-General -- something not seen in France since 1614 -- in order to pass new tax measures. The Estates-General, which would meet in May 1789 at Versailles, was composed of three separate assemblies, each receiving one vote, divided by medieval tradition into the following social orders:

- the First Estate, or clergy;

the Second Estate, or nobility; and the

Third Estate, which had meant middle class townspeople, but in 1788 was expanded to mean "the people." If the traditional consensus of the First and Second Estate held, the Third Estate would be virtually powerless.

The Third Estate

Early in 1789, the Third Estate, having collected long lists of grievances from the French people, known as cahiers de doleances, demanded increased representation in comparison to the other two estates. This argument is best articulated by the Abbe Emmanuel Joseph Sieyes in his widely influential pamphlet of February 1789 called What is the Third Estate? which asked three questions:

"1st. What is the third estate? Everything.

"2nd. What has it been heretofore in the political order? Nothing.

"3rd. What does it demand? To become something therein."

Tennis Court Oath

On 17 June 1789, after receiving various slights from the King, the Third Estate declared itself the sole National Assembly and invited the other two orders to join it. The King responded by locking out (perhaps accidentally) the Third Estate from its meeting hall. Assembling at a nearby indoor tennis court, the former Third Estate, bolstered and led by defectors from the nobles, like the Marquis de Lafayette, a hero for his service in the American rebellion against England, and from disaffected clergy such as Abbe Sieyes, declared its resolve to create what in effect would be a constitutional monarchy. All that was needed now was a spark to ignite France's growing discontent.

The Bastille Falls

Louis XVI wavered in response to the provocations of the representatives of the Third Estate, now calling itself the National Assembly. Hard-line advisors such as Louis XVI's younger brother the Count d'Artois, backed by Queen Marie Antoinette, urged Louis to confront and suppress this defiance. Others, like Finance Minister Jacques Necker, urged the King to assert himself and co-opt the reform movement. Louis XVI agitated both sides with his half-measures and equivocations, and soon various individuals began aggrandizing themselves in the absence of a central authority. Louis, meanwhile, greatly wished that he could spend his time hunting and not have to deal with the burgeoning crisis.

Events accelerated when Louis XVI decided to remove the popular Necker from his office on 12 July 1789. This, coupled with a build up of royal soldiers near Versailles, seemed to presage a reactionary crackdown and greatly provoked an increasingly fearful Parisian populace already alarmed by the events of 28 April, when royalist troops resorted to firing on a Parisian mob provoked by high bread prices. In response to Necker's dismissal, agitators backed by the Duke d'Orleans (the cousin and now rival of Louis XVI), gave impassioned speeches to take arms from the courtyard of the decadent Palais Royal, which had become a vocal center of dissent.

The Paris provincial government, alarmed by the possibility of violence initiated by either the King or the mob, took steps to organize and arm what became known as the National Guard, to protect both the National Assembly and the shops of Paris.

It was the frantic search for weapons and powder that led to the famous storming of the Bastille, a menacingly dark medieval fortress used mostly as a prison, on 14 July. Long believed to have been the work of the Parisian mob, in fact this action was undertaken primarily by middle-class Frenchmen of the militia. The Governor of the Bastille blundered when he ordered his men to fire into the insurgents, killing 98 and wounding 73 -- for this he paid with his life after he surrendered the garrison, his head being affixed to the end of a pike and paraded down to the city hall.

The symbolic significance of the fall of the Bastille -- as an end to royal injustice -- greatly overshadowed its military worth. Long rumored to be a prison where unspeakable deprivations and tortures took place, only seven prisoners were found in its dank cells. Its most famous recent prisoner, the Marquis de Sade, had been removed for agitating the crowds from his window days before the prison capitulated.

The reaction of Louis XVI was to recall Necker to his post, signaling the beginning of a long process of half-hearted appeasement and acquiescence by a monarchy hoping to survive the current turmoil and reassert its former powers.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man are issued

Inspired by philosophers such as Rousseau, Voltaire, and others -- and perhaps the presence in Paris of Thomas Jefferson -- the leaders of the National Assembly sought to make a stirring statement of their political ideals. This Declaration of the Rights of Man, written largely by Sieyes, was issued on 27 August 1789 and is among the most admired works in the democratic canon. It included such ideas as "Men are born free and equal in rights" and "These rights are liberty, property, and safety from, and resistance to, oppression."

After issuing the Declaration, the Assembly set about the political task of embodying its beliefs in what would become the Constitution of 1791. Political reality often fell short of the lofty rhetoric of the Declaration, among other things leaving nearly a third of the voting-age male population without the right to vote.

The Seizure of the King and Queen After a summer of chaos and violence in the provinces, in which peasant anger sparked widespread destruction of aristocratic property, the Parisian lower classes took center stage. Greatly agitated by the high price of bread, and by fears of counter-revolution instigated by the King's reactionary advisors, a large army of women conducted the famous march on Versailles on 5 October, where they literally seized the King, adorned him with the revolutionary cockade, and brought him back to Paris under escort of Lafayette's National Guards. Now a hostage of the powers in Paris, the King was little more than a figurehead.

The King and Queen Flee to Versailles

Impotent to control the Revolution through internal measures, Louis XVI, spurred largely by the "Austrian party" of Marie Antoinette, continued to scheme with his fellow monarchs aiming at his full restoration by use of foreign armies. Ultimately, the King decided to flee France in disguise on 20 June 1791. Incredibly, Louis and his family were recognized near the border by the postmaster of Varennes and were arrested and brought back to Paris.

This act embarrassed the efforts of moderates like Lafayette who were working toward creating a constitutional monarchy. Agreeing to the fiction that he had been "abducted," the King acquiesced to his new, more limited powers and endorsed the Constitution of 1791. However, few were fooled, and many now agitated for the removal and imprisonment of the King.

The confiscation of Church lands and the rise of the civil clergy

The Revolution was still plagued by the same problem that had brought down King Louis XVI -- a lack of money. The easiest solution to many seemed to be to seize and liquidate much of the enormous properties of the Catholic Church. This act in itself would have created little opposition in France. However, the National Assembly went even further by placing the clergy under governmental control. This was bitterly resented by many priests, particularly in the countryside of western France in the Vendee, Brittany, and Normandy, and would eventually lead to a bitter and hard-fought civil war against the Revolutionary governments in these regions.

Storming of the Tuileries

By April 1792, France was at war against Austria and Prussia. Accusations mounted against Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette that they were conspiring with foreign powers to regain power. The mob marched on the Tuileries Palace in the heart of Paris in June, and forced the King to wear the Cap of Liberty.

In a second incident, on 10 August, two large masses of citizens and National Guards converged on the Tuileries only to encounter resistance. Shots were exchanged. The King ordered his Swiss Guards to surrender while seeking shelter in the National Assembly -- his unfortunate mercenaries were massacred.

On 13 August, the royal family found themselves incarcerated in the Temple Prison. The French monarchy had ended. France was shortly thereafter declared a Republic.

The September Massacres

The September Massacres

In the late summer of 1792, talk of treason and betrayal was rife, and rumors of counter-revolutionary plots circulated throughout Paris. Adding to the state of alarm, a Prussian army was approaching, having issued the Brunswick Manifesto which promised punishment to anyone who harmed King Louis XVI. Reinforcing the panic and diminishing the credibility of a moderate course, Lafayette was accused of treasonous conduct and fled from France.

During 2-5 September, spurred largely by the rumors that the inmates would be freed in a plot to destabilize the city, the Paris mob seized several prisons, and, after conducting rather swift people's tribunals, executed over a thousand victims.

The Execution of Louis XVI

The Convention, now France's governing body, proceeded to place Louis on trial for treason. Secret documents discovered in the Tuileries helped to seal the guilty verdict. Also at issue was a power struggle between the moderates in the government, many of whom wanted to spare Louis XVI after pronouncing a legal death sentence, and the Jacobin radicals, who were looking forward to carrying it out.

The Jacobins prevailed. Citizen Capet, the former Louis XVI, was guillotined in the Place de la Revolution on 21 January 1793. This action not only signaled that the Revolution had truly crossed its Rubicon in arraying itself against the monarchies of Europe, but it also signified the rise to power of the Jacobins and their allies.

La Patrie en Danger

La Patrie en Danger

On 23 August 1793, the Convention mobilized the entire French nation for war with the declaration of the levee en masse. Many historians feel this marked an important transition to the beginnings of modern warfare and the birth of nationalism.

The Terror

Although fairly short-lived, images of the Terror -- cartloads of victims, howling crowds, and the ominous descent of "Madame Guillotine's" blade -- form the popular stereotype of the French Revolution.

By late Spring of 1793, the same year Buonaparte earned his first fame at Toulon (pp.32-33), treason and betrayal were the Republic's primary obsessions. A vicious civil war erupted in the countryside of the Vendee. Enemies abroad, including many French royalist emigres, plotted to overthrow the Revolution. For Maximillan Robespierre, it was a time to purge the nation of traitors. Prevarication and moderation would not suffice. The Republic would be preserved by fear. Thus, the infamous Terror emerged, an event that horrified the world at large, made a mockery of the ideals of the Revolution, and forever tarnished the legacy of 1789.

While the Committee of General Security organized a Jacobin police state, the primary agency of the Terror was the Committee of Public Safety, which included Robespierre among its members. More than 2,500 people were guillotined in Paris, and not only aristocrats. It is estimated that almost 20,000 were killed throughout France during the Jacobin Terror, the majority during June-July of 1794.

Thermidor, the execution of Robespierre, and the Directory

Robespierre's increase in the pace of killing in the summer of 1794 provoked a plot hatched largely by Joseph Fouche, a Jacobin terrorist worried about his own head. Known as the Coup of Thermidor, this ended the most radical phase of the Revolution and sent Robespierre and his brother, along with nineteen of their closest supporters, to the guillotine on 28 July (10 Thermidor). Thus, the Terror ended by consuming its creator. The subsequent reign of the Thermidoreans (Jacobins), who abandoned tight controls of the economy and the heavy-handed use of fear, ultimately yielded to economic distress and unpopularity. It was during this time that anyone suspected as a supporter of Robespierre was arrested, including Napoleon (p.34).

After he was released, the 25-year-old general (promoted for his success at Toulon) played a key role in saving the fledgling Republic. The Directory -- a five- man executive council -- came to power in the aftermath of Napoleon's "Whiff of Grapeshot" in October 1795 (p. 34). The Directory proved to be an ineffective, inefficient, and corrupt government whose most dominant figure was Napoleon's patron, the decadent Paul Barras.

The Directory also proved unpopular, and nullified an election in the Assembly that would have brought the royalists back into power. This coup, led by the regicides who had much to fear from the royalists, was known as the Coup of Fructidor (4 September 1797). The Directory would totter on until Napoleon's usurpation of power in 1799 (p.42).

Corsican Adventures

Napoleon viewed the outbreak of the Revolution as an opportunity for Corsica. He therefore obtained yet another leave of absence and returned to Ajaccio in October of 1789. Voted a Lieutenant Colonel in a somewhat rigged election, Buonaparte became involved in organizing the Corsican National Guard. He also petitioned the French Assembly to give Corsicans the full rights of French citizens, which were ultimately granted.

Paoli returned from exile, and Napoleon hoped to ingratiate himself at Paoli's side -- he was to be disappointed by a lukewarm reception from his hero.

Ultimately, Napoleon would side with the French Revolution and the Jacobins, while Paoli supported the clergy and retained his English sympathies. Lt. Colonel Buonaparte returned to Corsica in early 1793 to command the artillery on a military expedition on behalf of the Convention against the island of La Maddalena, a Sardinian possession. Paoli appears to have sabotaged this effort, and Napoleon met with failure when there was a near mutiny among the Corsican troops.

The Convention ordered Paoli's arrest, which provoking a small civil war in Corsica. The Buonaparte family found themselves expelled from their native island under threat of death by Paoli's forces. The entire Buonaparte clan fled, Napoleon barely escaping capture, and arrived on the coast of France as true immigrants, dispossessed, on 14 June 1793.

Napoleon, whose life had been constantly torn between two worlds -- France and Corsica -- now found himself faced with but one future, as a soldier of Revolutionary France.

More Napoleon: Introductory Guide

-

Introduction

Prejudice and Pride

Napoleon in Military School

The Young Artillerist's Double Life

Revolution & Opportunity

Women's Fashion During the Revolution

The Siege of Toulon

Napoleon & Josephine

Women's Fashion during the Directory

Fame & Glory: Italy

Fame & Glory: Egypt

Saviour or Usurper

Battle of Marengo

Civil Achievments

Enlightened Despot or Tyrant

Napoleon's Siblings

The Dawn of Gastronomy

Haydn and Beethoven

Women's Fashion during the Empire

Napoleon's Other Women

The Mashalate and Imperial Eagle

History's Greatest General?

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #17

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Napoleon LLC.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

Order Napoleon magazine direct