With Malta's siege broken and Axis superiority fast disappearing into the Russian meatgrinder, Axis hopes for a Mediterranean victory were extinguished. But several major actions remained to be played out.

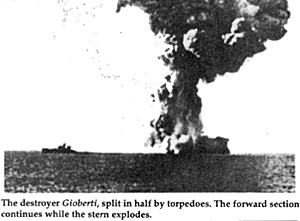

The destroyer Gioberti, split in half by torpedoes. The forward section continues while the stem explodes.

In November 1942, Anglo-American forces landed in Algeria (Operation TORCH). Except for initial spirited Vichy French resistance and sporadic bombing, the Axis powers made no move against the operation, other than to plan pipedream captures of Gibraltar.

There were several reasons for this nonaction. Germany was preoccupied with events in Russia, particularly the battle raging at Stalingrad. Italy's fleet was immobilized for lack of fuel and, more importantly, lack of air cover. The Allied brought with them a 5-1 air superiority. Even had the fuel and air support been available, the fleet faced a monstrous combined Allied fleet of 5 battleships, 5 carriers, 12 light cruisers, and over 100 escorts. Any sortie would have been a suicide mission, more for honor than substance.

During the next 5 months, the major Mediterranean conflict centered around Axis convoys to Tunisia. It was Malta in reverse. Allied strategic bombing was destroying the southern Italian ports, forcing the major fleet units north. One raid on Naples knocked the entire 7th Cruiser Division (three light cruisers, four destroyers) out of action. Convoys and escorts were hammered from air, surface, submarines and mines. In the battle, 243 ships were sunk and 242 damaged, including 167 naval units. One significant casualty was the valiant Lupo, lost in an action with four destroyers. On 13 May, Tunisia fell.

The next 2 months saw tremendous air bombardment in preparation for the invasion of Sicily. The Axis were split as to exactly where the landings would take place, with the Germans favoring Sardinia. But the real question was whether the Italian Fleet would be committed. The question would not have come up for Great Britain. Their doctrine would have called for fleet opposition to a homeland invasion, regardless of loss or numerical inferiority. But there were other considerations for the Italians. The fuel situation was much better now, but the location of the fleet units, due to the Allied bombardment, in the north put the fleet a day's sail away from any invasion theater.

Given the overwhelming air superiority of the Allies, the approaching fleet would in all probability be spotted and attacked en route. There was no air cover to speak of, and the Tunisian convoy battle had destroyed most of the escort ships. In fact, the fleet could muster Littorio, the new Roma, six light cruisers, and ten destroyers total to fight through Allied air attacks and face a superior Allied fleet. For these reasons Commando Supremo decided not to commit the Fleet except in event of a national collapse. It was a prudent, if not heroic, decision.

Operation HUSKY, the invasion of Sicily, got underway on 10 July. Involved were 2775 ships, including 280 warships and 4000 aircraft. The primary naval covering force consisted of 6 battleships, 6 light cruisers, 2 carriers, and 24 destroyers. Only MAS and submarines made attempts to interfere; eight submarines were sunk. Two long distance raids by Italian light cruisers came to naught. On 24 July, Mussolini, in the face of disintegrating Italian morale, was deposed. The end was in sight. It came with the Armistice on 8 September.

The final task of the Italian fleet was to escape the grasp of the Germans for internment in, ironically, Malta. Two separate groups, comprising five battleships (Littorio, now named Italia, Roma, Vittorio Veneto, Doria, and Duilia), 8 light cruisers, 7 destroyers, and 24 MAS boats made the journey. German aircraft, using glider bombs, damaged the Italia and blew up the Roma, the fleet flagship. The remnants of the fleet were scuttled or seized.

Sad to note: during the period of active warfare, the Italian fleet lost 193 vessels. An additional 220 vessels were lost before peace came to Europe. This total included heavy cruiser Bolzano, sunk by Italian maiale to keep her from being used by the Germans.

Summary

To quote Cmdr. Marc Bragadin from his book, The Italian Navy in World War II:

- "The African war was one of maritime supply, marked by a

struggle for naval and air supremacy at sea that would permit supplies

to flow freely."

That in a nutshell was the war in the Mediterranean. And, as was also proved in the Pacific, air power reigned supreme over naval forces. The struggle pitted Italy, a nation thrust unprepared into war by impulse and envy, aided by an "ally" for whom the theater was always a secondary diversion, against a British Empire being torn apart by world events, but served with aggressive resolve by a professional and committed service -- the Royal Navy. It was a struggle where several key decisions, on both sides, and events could have easily tipped the scales of fortune from what was to what might have been.

This was the war in the Mediterranean.

The Naval War in the Mediterranean 1940-1943

- Italians and British

The Opening Moves - 1940

Battle of Crete

Light Forces: Italians and British

Battles of Sirte

Malta Convoys

End Game

Italy's War Aims

State of the Regia Marina

Back to Table of Contents: CounterAttack # 2

To CounterAttack List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1988 by Pacific Rim Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com