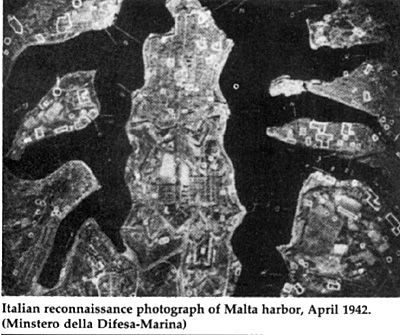

Malta had been given a slightly longer lease on life by the

supplies brought in March. But the air blitz intensified with Italian

planes and Fliegerkorps 11 and X hammering away relentlessly. In

April alone more than 9500 sorties were flown against the island,

dropping some 6700 tons of bombs.

Malta had been given a slightly longer lease on life by the

supplies brought in March. But the air blitz intensified with Italian

planes and Fliegerkorps 11 and X hammering away relentlessly. In

April alone more than 9500 sorties were flown against the island,

dropping some 6700 tons of bombs.

Italian reconnaissance photograph of Malta harbor, April 1942. (Minstero della Difesa-Marina)

In the middle of this firestorm, an attempt to reinforce the island's fighter defenses was made using the American aircraft carrier USS Wasp. Forty-six Spitfires were flown in, but they were caught on the ground and, within 3 days, had been wiped out. In early May, the last offensive punch of Malta, its submarines, was withdrawn from the island due to losses and the destruction of maintenance facilities.

On 9 May, 60 Spitfires from carriers Wasp and Eagle were flown in, and this time the island was prepared for them. The fighters began taking a heavy toll of the daylight raiders and the bombing slowly slacked off. As Rommel prepared for his Gazala offensive, Fliegerkorps 11 was assigned to his support. For all intents, the blitz had been beaten.

Operation Harpoon

But the island was still surrounded and in dire threat of starving due to lack of supplies. With the prospect of better fighter support near the island, the Admiralty decided to push supplies through in June. It was to be a two-pronged attempt. Operation HARPOON would leave Gibraltar with five freighters under the close escort of antiaircraft cruiser Cairo and nine destroyers.

Accompanying this force to the Sicilian Narrows would be battleship HMS Malaya and three light cruisers. Operation VIGOROUS, leaving Alexandria, would have 11 merchants with 7 light cruisers, 26 destroyers and HMS Centurion, an old target ship made up to look like a QE class battleship. VIGOROUS would be under the tactical command of Admiral Vian in HMS Cleopatra, but under the overall command of Admiral Harwood, the victor of the River Plate battle with the Graf Spee. Harwood had assumed command of the Mediterranean on 1 April, relieving Adm. Cunningham. It was not the best of changes. In particular, having the overall commander back in Alexandria during the operation would duplicate the problems that the Italians experienced throughout the war - that of slow command reaction to on-going events.

HARPOON got off to a good start, as the intense Axis air attacks were beaten off by the escort's heavy AA fire. But after the Malaya and her cruisers parted company, the convoy ran into the Italian 7th light cruiser division, made up of light cruisers Eugenia di Savoia and Montecuccoli, and five destroyers. HMS Cairo and four destroyers engaged to keep the Italians at bay. The Italians had a substantial range advantage over the Cairo's 4" guns and held target practice, scoring heavily against the cruiser and two of the destroyers. The British returned the favor by shooting up, two of the Italian destroyers attempting to break through to the convoy.

Cairo was forced to pull more destroyers away from the merchants to fight off the aggressive Italians. In doing so, the air attacks were able to press home their assaults and three of five merchants were hit. A respite was granted suddenly as da Zara withdrew to cover a gap in the minefields that the convoy was entering, allowing the escorts to regroup and recover. The Italian admiral has been widely criticized for this action, during which he thought he was engaged with a superior British force.

Cairo was able to send the two merchant survivors on through the minefield to Malta and prepared the others for scuttling. Da Zara reappeared and did the job for them, as well as sinking a destroyer and damaging another. But the Italians did not press home the attack against the fleeing merchants -- a costly error. Despite the error and the overall criticism leveled at Admiral da Zara, his action was one of the finest fought by an Italian naval force.

VIGOROUS's history is much more checkered. The convoy was pounded heavily while in route, losing one merchant quickly. However, Centurion's ruse seemed to work as the German pilots concentrated on her. Harwood received word via submarine that lachino with Littorio and Vittorio Veneto, two heavy cruisers and two light cruisers, had left port and were converging. Knowing that without help from the weather such as existed in March, the heavier Italian units would destroy his force, Harwood ordered the convoy to turn back. Submarine attacks on the Italian line erroneously reported hits on the battleships, and Harwood reversed his order.

Once again, the VIGOROUS convoy headed for Malta. When the error revealed itself via air reconnaissance in a wholly intact Italian battlegroup, Vian was again ordered to reverse course. Additional confusing reports made Harwood issue a fourth turnaround order, but this time, Vian continued back toward Alexandria. Harwood's final return order came a short while later. There was no surface contact, but opposing submarines scored for each side. Vian lost light cruiser Hermione and an Australian destroyer, while the British sank heavy cruiser Trento and - finally - put a real fish into Littorio.

VIGOROUS's return to Alexandria marked the dismal end to the June convoy attempt. Only 2 of 16 merchants made it to Malta, adding their cargoes to the meager stores there. Losses were severe, with many ships damaged. What was worse was the morale situation. The British had "run" from one engagement, and da Zara's cruiser action marked the first time that Italian surface vessels had scored significantly. It was a position the British didn't enjoy at all.

In the next two months, fortunes changed dramatically for the British. The air assault on Malta lessened to a degree where submarines were again stationed there. Their renewed presence in the vicinity of the Axis supply lines began to have a grave effect on the African situation. Rommel was stopped at El Alamein. More importantly, for the first time since the beginning of hostilities in the Mediterranean, Allied air strength was in rough parity with its Axis opponents, especially given the transfer of German units to the Russian conflict. But there was still Malta, starving in an Axis sea. Another convoy was imperative and in August Operation PEDESTAL, the most famous Malta convoy, was organized.

At Gibraltar, 14 fast merchants, carrying some 100,000 tons of supplies were gathered. In close support were light cruisers Nigeria, Kenya, and Manchester, antiaircraft cruisers Cairo and Charybdis, and 12 destroyers. In attendance were battleships Rodney and Nelson, 2 antiaircraft cruisers and 12 more destroyers. To provide the vital air cover were carriers Eagle, Victorious, and the new Indomitable.

To oppose this formidable force, the Axis mustered nearly 1000 aircraft, 20 submarines, new minefields, 23 MAS boats, and in reserve for the coup de grace, a division of 3 heavy cruisers, 3 light cruisers, and a dozen destroyers. For both sides the importance of the convoy was apparent and each was ready to do what was necessary. It was going to be a fight.

The Axis scored first as, early on 11 August, a U-boat penetrated the destroyer screen and put four torpedoes into carrier Eagle. The old ship sank, cutting the convoy's fighter umbrella by a third. The day's only air attack came at dusk, but failed to draw blood. Fortunes changed on the 12th. Over 100 Italian aircraft attacked but failed to score. One innovative attempt came close, though. Two Italian fighters, made up to resemble Hurricanes, joined the British fighters in their landing patterns after the attack, but the bombs they dropped on Victorious's crowded deck were duds. The attack could have taken the carrier out of the fight.

Later in the day, Indomitable wasn't so lucky. Stukas swarmed over the convoy, sinking a merchant and a destroyer, and hitting the new carrier three times. But overall, the 12th belonged to the British. The massed Axis air attack had failed miserably in its efforts.

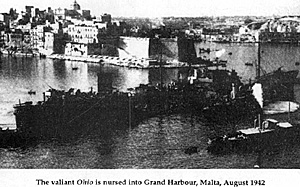

As night fell, the convoy began entering the Sicilian Narrows. The heavy escorts, the battleships and Victorious, turned back. With them went the British good fortune. PEDESTAL ran into a pack of waiting Italian submarines. One spread of torpedoes damaged Nigeria, the legendary tanker Ohio, and sank HARPOON survivor Cairo. Another took out two merchants and blew away Kenya's bow.

The confusion that ensued from the ambush continued into the night as the MAS squadrons struck. By the time the fast boats had disappeared, light cruiser Manchester and four merchants had been sunk.

On the 13th, air attacks again swarmed over the depleted

convoy, sinking two more merchants and heavily damaging several

others, including the apparently unsinkable Ohio (at right). But the key threat to

the survivors failed to appear. The Italian cruiser division, which would

have made short work of the surviving British escorts, was recalled by

Supermarina when the air cover promised the force did not appear. As

so many times in the past, the communications problems between

Supermarina and Superaereo, and between Italian and German, had

succeeded in thwarting Axis plans more effectively than anything the

Allies could do.

On the 13th, air attacks again swarmed over the depleted

convoy, sinking two more merchants and heavily damaging several

others, including the apparently unsinkable Ohio (at right). But the key threat to

the survivors failed to appear. The Italian cruiser division, which would

have made short work of the surviving British escorts, was recalled by

Supermarina when the air cover promised the force did not appear. As

so many times in the past, the communications problems between

Supermarina and Superaereo, and between Italian and German, had

succeeded in thwarting Axis plans more effectively than anything the

Allies could do.

Without the Italian surface interception, Malta air cover enabled the convoy survivors to reach Valletta safely. In all, five ships, including Ohio, and 30,000 tons of supplies were landed. Malta could breathe easy for the first time in nine months.

In retrospect, many things contributed to the convoy's success. Axis plans were thorough and the submarines and MAS units performed extremely well, but the Axis air assaults simply failed to penetrate the British screen and do their share. Of course, there was the final humility of the recalled cruiser division. Good Allied tactics, enhanced fighter protection, and poor Axis cooperation were keys in keeping Malta in the battle on the Allies' side. But even with the good luck and planning, PEDESTAL had been a very near thing. Without PEDESTAL's supplies, Malta would have been forced to surrender within weeks. The fact she remained untaken through the war was a major factor in the Axis losing the war. The failure remains one of the largest unanswered questions of WWII.

Malta

Historians agree that a key strategic mistake made by the Axis was not capturing the fortress of Malta. A study of the fortunes in North Africa shows an indisputable correlation: when Malta was neutralized, the Axis went east toward Egypt; when she wasn't, they retreated west. The reasons for the failure to capture this key Mediterranean position lies in both Berlin and Rome.

The key figures in Malta's fortune on the German side were Hitler, Kesselring, and Rommel. To the two subordinates, Malta was a required target, but Rommel usually tempered his opinion with the tactical judgments of his own command. Kesselring felt, as Goring did about England, that an air bombardment would pave the way to an easy capture, or indeed, an outright surrender. He was very nearly right, but he made the same mistakes Goring did: he never completed the destruction of one target (airfields, port facilities, defense emplacements) before switching the attacks to another target.

But the real key was Hitler. To him, the Mediterranean had always been a secondary theater. He had entered the fight solely to bolster Italy's flagging fortunes and to protect his southern flank before his invasion of the Soviet Union. To him, the Mediterranean was a diversion that kept the British busy while he tended to business in the east. It never occurred to him that his foray into Russia was the "diversion" Britain needed to stabilize the Mediterranean in its favor.

For the Italians, especially Mussolini, war was an impulse - a quick land grab from a foe weakened by events in Europe and the start of a colonial empire. But he failed to prepare adequately for the conflict which he saw as a short-term proposition. For the short term, Malta could be neutralized from the air; it would fall later. From the start the Italian war machine had no real direction. It lost the initiative and very nearly everything else.

Once the Germans came in, the Italians assumed a secondary role, despite the position they held in the region. It became their contention that they could not take Malta without German help. Events proved them correct. The Italian Air Force alone could not neutralize the island. It was only when the Germans were present in force that Malta could be silenced. It led to the Maltese prayer, said when an air raid alert was sounded, "Please, let it be the Italians!"

Operation Herkules

The most complete preparations for the capture of Malta came during the blitz of early 1942. The Luftwaffe had basically neutralized and isolated the island and Rommel had pushed back to the Gazala line. All parties concerned felt the time was ripe for Operation HERKULES, code name for the invasion. Preparations were started, Italian paratroops trained, sea landings practiced, glider strips built. The plan involved General Student's elite veteran Fallschirmjager Division, and the German-trained Folgore and Spezia Air Divisions for the initial landings, followed by five aeaborne Italian divisions. A total of 100,000 men (six times the force that captured Crete) were against four isolated, half-starved infantry brigades (30,000- 35,000 men) garrisoning the island. It was scheduled for May 1942.

But on the Gazala line, Rommel was observing a British buildup and argued that if he didn't attack first, Malta would be a mute point. Hitler agreed and the priorities were set. Rommel would attack the Gazala line and take Tobruk, then HERKULES would be launched.

Things went basically according to plan. Tobruk fell, but Rommel kept going. In his defense, it should be pointed out that he was as aware as anyone of the threat that Malta, unneutralized, posed against his supply lifeline. But he found himself facing a weak and dissolving British foe, with Egypt and the Suez tantalizingly close. He wanted to exploit the situation; and Hitler, mesmerized by the brilliant successes of the new Field Marshal agreed.

Mussolini, with internal dissension among his HERKULES commanders concerning the operation's potential success, went along. In the end, however, Malta had the last word. With Spitfires countering the diminishing Axis air assault, Malta again went on the offensive against Axis supply lines. Rommel starved and went west for the final time.

Final Question

A final question exists: if HERKULES had been initiated, would it have been successful? There are a lot of opinions. The Italians say yes, given prompt German support in the form of air power, paratroops, and fuel oil. But the support was the critical item. The Italians had been forced to pump fuel OUT of their battleships to feed the merchants going to Libya. Without the support, the Italians weren't even going to attempt the invasion. The German field commanders, Kesselring, Student, and Ramcke were optimistic, particularly over the abilities and morale of the Italian paratroops.

But Hitler was unconvinced. He was still conscious of the bloodbath on Crete that decimated his elite paratroops, and he remained derisive of the Italian's fighting ability and resolve. He was positive that if the British Royal Navy intervened during the operation, the Italian fleet would run and leave the paratroops stranded. Arguments that air superiority would lead to a another slaughter of British ships, such as the one off Crete, fell on deaf ears.

For the British, the invasion posed less of a threat than that of starvation. Their intelligence was better, and they felt the initial landings would have been mauled worse than the ones on Crete. The Royal Navy would have intervened simply because, with the disasters in the Far East and the fall of Tobruk, the British morale at home would have demanded a total attempt to hold the island. If the fortress had fallen, a government collapse would have been a distinct possibility. From a tactical viewpoint, several major differences between Crete and Malta would have affected the chances of success.

First, the antiaircraft strength on Malta was extraordinary. The flak over Malta was greatly feared by the Axis pilots. This difference may have been partially neutralized by the night glider landing planned in HERKULES to eliminate AA positions in the main landing areas. Second was simple geography. Malta was smaller than Crete. There was no place where Axis forces could regroup unseen. The island was criss-crossed with stone walls, limiting the possible landing areas, and creating problems for advancing infantry once on the ground. And the area picked by the Italians for the primary sea landing beaches was essentially blocked by cliffs, hard to handle by experienced troops in the daylight, nearly impossible for inexperienced troop at night as was planned! Finally, Malta was far enough away from enemy ports to have to rely on seaborne supply until a port was captured, increasing the potential for effective Royal Navy intervention. The British were confident that an Axis invasion would have failed.

Looking at the situation in hindsight, HERKULES had a chance of success from a military point of view, but died on the political table. The Axis "partners" simply didn't trust each other, and cooperation was minimal at high levels. Both would have been ready to pull out immediately at any sign of hesitation by the other. If Axis cooperation had not been as strained as it was, Malta in all probability would have been taken, with an extraordinary effect on the war.

The Naval War in the Mediterranean 1940-1943

- Italians and British

The Opening Moves - 1940

Battle of Crete

Light Forces: Italians and British

Battles of Sirte

Malta Convoys

End Game

Italy's War Aims

State of the Regia Marina

Back to Table of Contents: CounterAttack # 2

To CounterAttack List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1988 by Pacific Rim Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com