The respite given the Allies by Italian neutrality in 1939 had

both good points and bad, as discussed previously; the respite Italy

gave the Royal Navy in 1940 cost the Axis the war.

The respite given the Allies by Italian neutrality in 1939 had

both good points and bad, as discussed previously; the respite Italy

gave the Royal Navy in 1940 cost the Axis the war.

The first time a carrier had acted in coordination with a surface fleet." (Hutchinson's Pictorial History of the War)

This respite was the lack of offensive action on the part of the Italian fleet against a weak, scattered foe. The blame for this lay squarely with Rome and Commando Supremo. Two reasons have been mentioned before. First, Supermarina felt itself weaker than its opponent and adopted a defensive posture. Second, Italy lacked a sufficient stockpile of fuel oil to sustain any large offensives.

But the underlying cause was Mussolini's view of Italy's role in the war. Italy entered the war when she did solely because of her leader's envy at Hitler's success. It was virtually a snap decision, catching Commando Supremo by surprise. None of the armed forces was prepared with plans of action - in fact, there was no strategic plan at all.

A good example of just how inopportune the declaration of war was lies in Italy's merchant shipping and her fleet. Mussolini's call for war caught over a million tons of Italy's merchant shipping either on the high seas or in foreign ports, causing a loss she could ill afford, given her poor stockpile status.

In addition, four of her six battleships, including both new Littorio class ships, were still refitting in the shipyards and were out of action for the first 2 months. Had the British possessed a sizable strategic bombing force in the Mediterranean, these ships might not have seen action at all!

Had Italy waited (or at least thought) to declare war, her merchant shipping would have been collected and her fleet would have been at full strength. Perhaps even a comprehensive plan of action might have been prepared. As it was, the first offensive move in the war came several hours after war was declared - a ten plane raid on Malta. There should have been plans to assault - or at least neutralize - the three main British bases, Gibraltar, Malta, and Alexandria.

There was a German plan to take Gibraltar with the aid of Franco's Spain, which was frustrated by the latter's neutrality. Italy had a plan for the capture of Malta in 1940, which at this point was extremely weak, but there had been no preparation for it and the plan was discarded. In short, Italy's leaders started her into a war with no true direction, a lack of which hampered her capabilities and destroyed her reputation, both abroad and at home.

Italy's lack of offense meant that Britain could turn to a poten. tially serious problem - that of the French fleet. Although the Franco- German armistice declared specifically that the fleet could not be used by the Axis, Britain was not certain that the Vichy Government wouldn't be persuaded to allow the fleet to join the Axis cause. Therefore, with misgivings but total resolve, Britain's Royal Navy took the initiative, neutralizing the French fleet in two main actions -- at Mers el Kabir by bombardment and at Alexandria by maneuver and diplomacy. By mid-July, the French threat had been eliminated.

Despite the French fleet's neutralization, the British were still

in a vulnerable position. Early on, however, Adm. Cunningham

decided to pursue an aggressive policy. A major decision taken was

that Malta was to be held, reinforced, and ultimately used by light

forces against the Axis supply lines to Africa. Another decision led to

the first major sea action between the combatants.

Despite the French fleet's neutralization, the British were still

in a vulnerable position. Early on, however, Adm. Cunningham

decided to pursue an aggressive policy. A major decision taken was

that Malta was to be held, reinforced, and ultimately used by light

forces against the Axis supply lines to Africa. Another decision led to

the first major sea action between the combatants.

Cape Spartivento

Needing reinforcements for Alexandria, Cunningham decided to force the central Mediterranean with the new ships and a convoy to Malta. The naval forces involved included the carrier Eagle, battleships Warspite, Malaya, and Royal Sovereign; five light cruisers; and six destroyers.

On 9 July 1940, this force ran into an Italian fleet returning from convoy duty to Africa off Cape Spartivento. The Italians were led by their older battleships Cavour and Cesa, 6 heavy cruisers, 12 light cruisers, and accompanying destroyers.

Although outnumbered, Cunningham forced the action with Eagle's aircraft attacking the Italians to no avail. In the naval fight the Cesare took one hit from Warspite and heavy cruiser Bolza took several 6" hits during the cruiser action. The Italians broke the action, covering their withdrawal with a destroyer torpedo attack.

It was an important engagement, despite the lack of mate damage. It was the first time a carrier had acted in coordination with a surface fleet. It was the first chance for both sides to study their respective air-sea tactical doctrines. The Italian high level bombing was shown to be particularly frustrating -- and nearly disastrous as they repeatedly bombed their own ships. The action led to a very bitter fight in Rome between Supermarina and Superaereo, leading to lowered Italian morale. Finally, and most importantly, it showed Cunningham that the Italians, despite their material preponderance, could not deny him access to the Central Mediterranean.

Italian Morale

Italian morale continued to be lowered by the results of smaller actions in the region. One light cruiser was sunk and another damaged in a skirmish on the 19th; several destroyers were lost to both surface vessels and incessant Fleet Air Arm attacks on Axis harbors. Effectively unopposed, the Royal Navy conducted sweeps of the Mediterranean, hoping to lure the Italians out to battle, ran convoys to both Malta and Alexandria, and raided exposed Italian bases, causing Supermarina to abandon them.

The only offensive gestures shown by the Italians during this time were their raids on Malta and, on 20 August, a raid on Gibraltar. This lack of opposition led to the British occupation of Crete, only days after the Italians declared war on Greece. From there, British aircraft played an important role in the early battles and ultimately led to one of the bloodiest fights of the War.

But Cunningham wasn't satisfied. Regardless of Italian inaction, their fleet posed a threat to his control, especially since late August when her other four battleships came into service. This threat had to be countered with a fleet that badly needed refitting, especially the older battleships.

Air Attack on Taranto

Therefore, he decided that if the Italians weren't going to come to him, he'd go to the Italians. Using the newly arrived carrier Illustrious and her complement of old Swordfish bombers, he attacked the Italian anchorage at Taranto in one of the most daring and successful operations of the war.

On the night of 11 November, two waves of Swordfish swept through the intense flak of the harbor and dropped their fish. Set to run under the Italian torpedo nets around the capital ships, the torpedoes struck home with telling effect. Cavour was struck only once, but her old bulkheads gave way and, although she was refloated, she never saw action again. Duilio, a 12.6" battleship and the new Littorio were each hit, knocking both out of the war for 6 months. At the cost of two aircraft, half the Italian battleship strength was effectively taken out.

The victory gave Cunningham three big advantages. First, he was able to retire his older battleships home for well needed refits. Second, it caused the Italians to move their major fleet units to anchorages further up the coast, away from the main theater of action. And finally, it was one more victory in his campaign to beat the enemy's morale.

This last advantage was perhaps the most important. The rest of the year was the Royal Navy's. An inconsequential duel between battleships and the daring bombardment of Verona, where the Italians learned a bitter lesson about adequate recon, only served to deepen the hold Cunningham had on the Italians. Against all the odds, his aggressive policy had proved itself, allowing the British to retain and strengthen what had been a very tenuous hold on the Mediterranean.

Cape Matapan

By the end of 1940, The British had things pretty much their way.

They had cowed the Italians into inaction; Malta was being steadily

strengthened and reinforced, and Alexandria had been reinforced.

By the end of 1940, The British had things pretty much their way.

They had cowed the Italians into inaction; Malta was being steadily

strengthened and reinforced, and Alexandria had been reinforced.

HMS Valiant and HMS Barhman firing broadsides at Cape Matapan. (Hutchinson's Pictorial History of the War)

In January 1941, however, things changed. The Germans, angered and worried about the Italian reverses, intervened. Troops were sent to Africa and Luftwaffe units sent to Sicily.

Within days of Fliegerkorps X's arrival, Cunningham found out just how effective dive bombers could be. On 11 January, his only carrier, HMS Illustrious, was ripped apart off Malta by Stukas and their 1100 pound bombs. She survived solely by good fortune and undamaged engines. Malta became the target of intensive raids, and HMS Southhampton was caught alone and sunk. Suddenly, the Central Mediterranean was no longer safe for Cunningham's ships.

In March, the Germans began to focus on the Balkans. They persuaded Commando Supremo to commit the Italian fleet against the British troop convoys in the Aegean area. The deciding factor was a German intelligence report indicating only one British battleship as currently serviceable. The orders were cut and given the Admiral Angelo lachino, the newly appointed Italian Fleet commander. Iachino was an intelligent, respected naval officer, well versed in tactics and gunnery. Given a different command structure, he might well have changed Italian fortunes in the Mediterranean. He was, as events bore out, aggressive but unlucky. The planned sortie he had been given was tightly controlled by Rome, with air cover and support mapped out for the entire venture. Iachino had strong misgivings about the operation, especially about the air support, but he set sail with 6 heavy cruisers and 2 light cruisers, divided into two divisions and flagged by the new 15" battleship Vittorio Veneto.

In Alexandria, Cunningham, alerted by the increased number of Italian reconnaissance flights over the harbor, decided a major operation was in the works. His plans from that point on were aimed not only at protecting the troop convoys under his command, but also at destroying any Italian naval forces involved, particularly any battleships involved. He hoped to finish what 1940 had started. His main battle fleet was built around three battleships - not the one that the Italians were expecting - and the newly arrived armored carrier Formidable. Scouting ahead of this formidable force was Admiral Pridham-Wippel with four 6" light cruisers.

The Italian cruisers Pola, Zara, and Fiume lost at Cape

Matapan

The Italian cruisers Pola, Zara, and Fiume lost at Cape

Matapan

From the outset, the British were plagued with reconnaissance communications problems which would ultimately foil Cunningham's goals. Reconnaissance planes ahead of the fleet reported two separate groups of strange ships, both approximately the same size as Pridham- Wippel's force, causing the latter to believe his ships had been sighted by the British pilots. In actuality, both Italian cruiser divisions had been sighted.

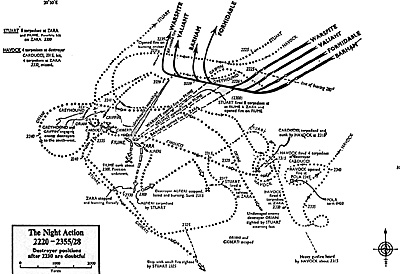

Thus, on 28 March the British light cruisers ran headlong into the Italian 1st Cruiser Division (1CruDiv) and came under fire from their 8" main rifles. Totally outranged, they turned and steamed back toward Cunningham's main body, hoping to draw the Italians under the guns of the British battleships. However, after a fruitless chase, firing at the snaking British line, the Italians reversed course and headed west on orders from Iachino.

Pridham-Wippel followed suit to shadow this force, not knowing that the Italians were pulling the same trick on him that he had just tried. The Vittorio Veneto was sailing to converge on the British.

At 1100 hours, the trap was sprung. At a range of 12 miles (21,000 yards), the Italian battleship opened fire. Pridham-Wippel immediately turned tail and ran under cover of smoke, but Iachino's flagship followed at speed, continuing to rain accurate but wide spread fire on the fleeing light cruisers. The British at this point were in serious trouble; they couldn't outrun the Vittorio Veneto and 1CruDiv was also again closing into range.

Cunningham launched Formidable's aircraft to aid the beleaguered cruisers, but once again communications nearly caused a disaster. His message to Pridham-Wippel read simply "Torpedo attack on the way", from which the cruiser commander interpreted that an Italian strike was coming in. He ordered his ships to fire on the planes.

Despite the mix-up, the airstrike did its job; the Italian battleship was forced to dodge the whole attack and broke off its pursuit of the British. The returning pilots reported at least one hit on her. Taking this to be true, Cunningham paused to recover his aircraft.

Unfortunately for the British commander, the Vittorio Veneto had not been hit and the Italians gained time and distance from the main body -- it would prove to be an insurmountable lead.

Iachino, frustrated at his two missed chances at the British light cruisers and angered because of NO air cover at all, felt justifiably unable to continue the operation in the face of total British air superiority. The Italians joined up and retired to the west, harried by continued strikes from Formidable's aircraft and from the British base at Maleme, Crete.

His worries came true as, in mid-afternoon, the Vittorio Veneto was hit aft by a torpedo and her engines stopped. She was soon able to proceed but at a much slower speed. The British were now faster in force than the Italians and they began closing the gap. Cunningham began to think in terms of a night action, deciding upon a destroyer torpedo attack followed by a fleet engagement.

The night events that followed were set up by the last British air strike of the day. Heavy cruiser Pola took a fish amidships and flooded her boilers. Iachino, upon getting the damage report, dispatched the rest of the 2nd Cruiser Division (2CruDiv), heavy cruisers Zara and Fiume and four destroyers, back to aid the stricken ship. He felt a flag officer should be there to make t e necessary decisions and to help protect his valuable cruiser from what he expected to be, at most, a British destroyer attack. His own reconnaissance sightings had been worse than Cunningham's, and he still had no knowledge of the British battleships. Overall, his decision reflected the rigidity of Italian command structure an naval tactics.

Meanwhile, Cunningham, with Pola showing on his radar homed in on what he thought was the damaged Vittorio Veneto. The entire force was then surprised to sight 2CruDiv sailing in line across their bows at a range of 4000 yards. As the British we prepared for a night engagement, their surprise soon turned action and the battleships opened fire at point blank range on the unsuspecting Italians. Some 19 broadsides were loosed in the minute span, and the two heavy cruisers were virtually blown of the water without firing a shot.

The Italian destroyers attacked the overwhelming line courageously, losing two of their number but forcing the British to evade the attacks. In doing so, they turned their course away from the main chase. It was, in fact, this attack, combined with the earlier pause to recover aircraft, that ensured Iachino's remaining force would reach harbor safely.

Nearly an hour after Zara and Fiume met their flaming end, a British destroyer stumbled upon stricken Pola. The cruiser's internal power had not been restored and her crew was demoralized and, by most accounts, drunk. She went down to a torpedo after the crew had been taken off. With her sinking, the battle of Matapan came to its conclusion.

Lessons

For the Italians, Matapan taught several hard lessons. First, the worth of an aircraft carrier proved itself as opposed to land based air support, which had been nonexistent. Mussolini authorized the immediate construction of a carrier for the fleet (Aquila - never completed). Second, radar proved a significant factor in the battle, solving at least one of the technological problems that convinced the Italians that night engagements were unrealistic; their scientists began working on the systems again -- a unit was installed on Littorio but proved inconsistent. Third, Supermarina became very aware that its tactical doctrines were deficient, especially in night actions. The Italian fleet was ordered to avoid them in the future until Italian technology made them feasible. Unfortunately, the major problem of sea-air coordination between Supermarina and Superaereo, while intensely argued, was never solved, despite the loss of five ships and some 2000 lives directly attributable to it.

For the British, the battle was a staggering success. They had evaded a dangerous situation and had turned the tables to destroy five new ships for the price of a single aircraft and her crew. But the battle also proved frustrating in the extreme. Confused and inaccurate sighting reports, compounded by faulty interpretation, had caused Cunningham to miss an opportunity to catch and sink another Italian battleship. Radar had proved its worth but it still had to be mastered - it had taken a visual sighting by HMS Stuart to alert the fleet to the presence of the Italian cruisers that night.

In summary, the battle was a tremendous British victory in the tactical sense. Their convoys proceeded to Crete and Greece unmolested from the surface. The Italians had been dealt another hard blow to their morale. The battle gave Cunningham virtual control of the sea, which proved necessary as the Greek campaign came to a close and thousands of British soldiers needed to be evacuated. Strategically, the Italians remained strong enough to prove a threat to British interests in the Mediterranean despite the loss of three heavy cruisers.

And while a British battlefleet never again made contact with an Italian battlefleet, they were to contact another type of fleet which would shatter their supremacy. This new fleet was in the air.

The Naval War in the Mediterranean 1940-1943

- Italians and British

The Opening Moves - 1940

Battle of Crete

Light Forces: Italians and British

Battles of Sirte

Malta Convoys

End Game

Italy's War Aims

State of the Regia Marina

Back to Table of Contents: CounterAttack # 2

To CounterAttack List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1988 by Pacific Rim Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com