Part I: George Washington and Jumonville Glen

Part II: Reaping the Whirlwind: Fort Necessity

This could have had serious repercussions among the few Indians that remained to Braddock, but the solemnity of the resultant funeral ceremony seems to have smoothed things over.

Washington himself, slowly recovering from his illness, had been obliged to ride in a covered wagon and did not catch up with Braddock until the 8th of July. He was two miles from the Monongahela. After a night's rest, with the aid of pillows tied to his saddle, he was finally able to mount a horse and watch as the army moved out.

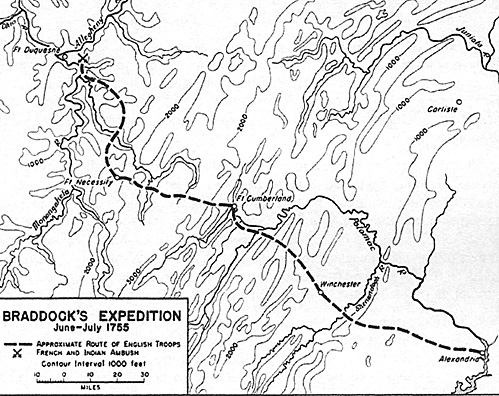

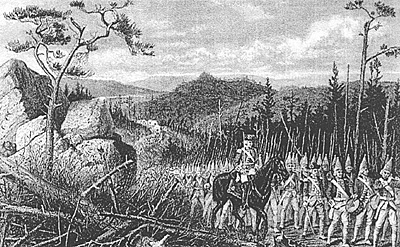

In order to avoid an area of difficult ground, it had been decided to cross the Monongahela twice, where the river made a sort of horseshoe, near the mouth of Turtle Creek. Two appropriate fords were located and the engineers set to work to level the river banks so that the wagons and artillery could cross. It was in an atmosphere of caution that the final crossing of the river was made. All were of the opinion that if any attack were to be made on the long line of British troops it would be here. Accordingly, the crossing was made in textbook fashion with plenty of security. Nevertheless, a certain amount of fanfare seemed to be called for, and the army marched with flags unfurled and martial music playing. Washington would later recall that the sight of the army in motion was the most thrilling of his entire life. [17]

It looked like it was going to be a walk in the sun. Thomas Walker, commissary of the Virginia forces would later write:

"A finer sight could not have been beheld. The shining barrels of the muskets, the excellent order of the men, the cleanliness of their appearance, the joy depicted on every face at being so near Fort Duquesne, the highest object of their wishes. The music re-echoed through the mountains."

[18]

On the far side of the ford stood the charred remains of Fraser's Fort, a trading post that had been burned by the French the previous year. This ruin was a mere eight miles from Fort Duquesne via a winding trail. In the lead were the scouts, Croghan and Gist, along with Scarouyady and the eight Indians who had chosen to stay with Braddock's army. [19]

Some fifty yards behind came Gage's advance party, but no longer with the two 6-pounders that would have accompanied it, Gage having deemed their presence unnecessary.

[20]

Next came the working party consisting of the road cutters and bridge builders, along with a long line of wagons. A hundred yards behind them came the van of the main body consisting of 29 Virginia horse under Captain Robert Stewart followed by the detachment of sailors and pioneers. One hundred yards behind them came the main body, with Braddock riding at its head accompanied by his aids, Orme and Washington. Colonel Ralph Burton led two 250-man columns on either side of a column of the guns, wagons, and carriages, flanked by cattle and horses. A hundred yards further back came the hundred-man rear guard under Sir Peter Halkett that included Adam Stephens's Virginia Regiment. On either side of the line were two dozen flanking parties. In addition, there were some 250 personal servants, soldiers' wives, sutlers, teamsters, and volunteers in the column.

The forest through which they marched consisted of a mature hardwood forest. St. Clair would write, "this wood was so open that carriages could have been drove in any part of it."

[21]

Whether or not St. Clair was exaggerating, most accounts seem to agree that the woods were not dense, although they would seem to have afforded enough cover for those waging war in the "Indian fashion" to benefit from it. To the right of the British line of march, around a mile from the river, there arose a hillock. Amore careful advanced guard would not have failed to occupy it, however Gage did not have this done. Perhaps he was lulled into a false sense of security by the peaceful river crossing.

And what of the French? On the 24th of May, the Sieur de Contrecoeur, who commanded there, had been able to report to the Marquis Vaudreuil that "the works at Fort Duquesne are completed. It is at present mounted with six pieces of cannon of six, and nine of two [or] three pound ball [and is] in want of neither arms nor ammunition." [22]

In early July, the fort's complement of men had swelled from the mere one hundred French and Canadians and like number of Indians who had wintered there to over six hundred souls. In addition, there were upwards of eight hundred Indian warriors present. [23]

Although Captain Contrecoeur had known for some time that the British were planning an expedition against Fort Duquesne, it was not until the 6th of July that he was apprised that they were in the vicinity. He seems initially to have underestimated their strength, and then subsequently overestimated them has having three to four thousand in their ranks.

Clearly something had to be done, and quickly. Someone suggested an ambush. The exact author of this idea is not known for certain; it was either one of three captains present, Contrecoeur, Beaujeu, or Dumas, or possibly Langlade, the Indian agent. Proper accreditation is really not important as the choice of an ambush of British regulars in march column in the woods by forces trained and experienced in irregular wilderness fighting would seem to have been fairly obvious. In the event, what transpired was not really an ambush.

"The next morning M. de Beaujeu left his fort with the few troops he had and asked the Indians for the result of their deliberations. They answered that they could not march. M. de Beaujeu, who was kind, affable, and sensible, said to them: `I am determined to confront the enemy. What - would you let your father go alone? I am certain to defeat them!" With this, they decided to follow him."

[24]

What followed was not an ambush. In fact, Beaujeu seems to have underestimated the speed with which the British were advancing and ran into the advanced guard under Gage at around 2:00 PM. The British scouts were the first to see the advancing French and Indians. They quickly ran back to warn the advanced guard under Gage. These men halted, fixed bayonets, and formed a firing line. A group of what seemed to be 300 or so Indians was seen advancing led by an officer dressed as an Indian save for his hat and gorget. This was Beaujeu. As he waved to his men with his hat, they peeled off to either flank and began ducking behind trees.

The British line began firing regular volleys at nothing in particular, as by this time there were very few visible enemy troops. Nevertheless, on the third volley, Beaujeu went down with a bullet through his head. Some of the French and Canadians began to retreat when they saw Beaujeu's fate, but Captain Dumas showed that he was up to the task of leadership as he took over command and rallied the troops. Taking the path of least resistance, groups of French and Indians began to make their ways down either flank of the British column.

As Sir John St. Clair raced forward to find out what was happening, he received a bullet through his chest and shoulder, but somehow managed to maintain his feet. Gage in the meantime was trying to rally some of his men to seize the high ground to the right front of his position, but to no avail. The men refused to advance. Some of them even turned and ran, running into the carpenters and rangers who were following behind. Those who didn't run continued blazing away in all directions, some of them inadvertently killing members of their own flanking parties.

St. Clair had made his way back to the carpenters and rangers and now had the two 6-pounders deployed that should have been further up with the regulars but for Gage's negligence. Their blasts into the bushes, although impressive sounding enough, only served to encourage the French and Indians to continue to pour around the flanks from where they could pick off gunners and raise holy Ned with the intertwined and muddled ranks of both Gage's and St. Clair's detachments. By now, all attempts to take the high ground on the right had come to naught, and it was occupied by the French and Indians who proceeded to make good use of it. Then news that the baggage train was under attack prompted the survivors of the advanced guard to cut bait and run.

In the meantime, Braddock, who had heard the commotion and sent an aid forward to find out what it was about, had decided to order Burton's 800 men to form a line four men deep and advance, along with the three 12-pounders. Since this formation was in two columns astride the baggage train, it took some time to perform this maneuver, complicated in part by the fact that the orders were misunderstood by some to form a line eight men deep. As the men tried to shake themselves into some order under a galling fire of musket and rifle fire, especially from that accursed hill on the right, in came crashing the fugitives from the advanced guard. At this point, disorder reigned as those in front tried to push their way back and those behind tried to push their way forward. This presented a target that was difficult to miss.

As Braddock and his aides (including Washington, we would presume) rode up, a bleeding St. Clair entreated with the General to seize the hill on the right before passing out from loss of blood. Braddock ordered Burton to advance on the hill with 150 men. Burton, with much difficulty, was able to get 100 men of the 48th together only to be shot out of the saddle for his efforts. This put the kibosh on the morale of his men who only too quickly made their way back to the road.

Braddock continued to importune his men to form themselves into orderly firing divisions, for it was in its marvelous firepower that the strength of the British army lay. Captain Waggener, on the other hand, was all too familiar with wilderness warfare and purposed to lead his Virginians forward in open order, taking advantage of the abundant cover that Nature had provided. Washington too, apparently suggested to Braddock that the French and Indians could be defeated by skirmishing troops and asked permission to send 300 men into the woods.

According to Bill Brown, Burton's Negro servant, Braddock responded by threatening to run Washington through with his sword. Then, observing Washington's frail condition and padded saddle, he relented a bit and ordered a former Coldstream Guardsman to watch over the young man. In the event, permission to attack a la debandade was denied. [25]

Part I: George Washington and Jumonville Glen

George Washington and the Seven Years War Part III: Into the Fire: The Braddock Campaign

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. The details of Braddock's march have been so often repeated that we shall here present but a brief summary. Despite Braddock's stern precautions, a few casualties nevertheless occurred within his party. These involved men who were detached from the main party and were picked off and scalped by Indians who were monitoring the progress of the task force. Of a more serious nature was the accidental shooting of Scarouady's own son by a group of nervous soldiers who had mistaken him for a hostile.

[16]

The details of Braddock's march have been so often repeated that we shall here present but a brief summary. Despite Braddock's stern precautions, a few casualties nevertheless occurred within his party. These involved men who were detached from the main party and were picked off and scalped by Indians who were monitoring the progress of the task force. Of a more serious nature was the accidental shooting of Scarouady's own son by a group of nervous soldiers who had mistaken him for a hostile.

[16]

Beaujeu, who had been given the task of heading up the ambushing force was having problems of his own. First, Contrecoeur would only let him have a third of the French and Canadians of the garrison of the fort. Second, the Indians were showing a strong desire to stand down and not fight a superior foe. Throughout the night of July 8th Beaujeu had vainly entreated his Indian allies to join him in an attack on the British. The Indians demurred and said that they would make up their minds in the morning. An excerpt from an anonymous French account follows:

Beaujeu, who had been given the task of heading up the ambushing force was having problems of his own. First, Contrecoeur would only let him have a third of the French and Canadians of the garrison of the fort. Second, the Indians were showing a strong desire to stand down and not fight a superior foe. Throughout the night of July 8th Beaujeu had vainly entreated his Indian allies to join him in an attack on the British. The Indians demurred and said that they would make up their minds in the morning. An excerpt from an anonymous French account follows:

Part II: Reaping the Whirlwind: Fort Necessity

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. XIII No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by James J. Mitchell

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com