George Washington looms larger than life in the history of the United States. Known as the nation's first president and the "father of his country," he has been the subject of countless biographies, some with such lofty names as All Cloudless Glory or Washington: The Indispensible Man. Since the times of Parson Weems, history has often been replaced by myth and reality by fable. That Washington was a great man is self-evident. But that he was not born to greatness; but had to work at it, is less well known. The era of the Seven Years War bore witness to the formative years of his character and provides us with a portrait of a young man still trying to make a name and a fortune. That this quest for self improvement was so intimately bound up in the North American theater of the Seven Years War makes the details of Washington's early years only that much more fascinating.

George Washington looms larger than life in the history of the United States. Known as the nation's first president and the "father of his country," he has been the subject of countless biographies, some with such lofty names as All Cloudless Glory or Washington: The Indispensible Man. Since the times of Parson Weems, history has often been replaced by myth and reality by fable. That Washington was a great man is self-evident. But that he was not born to greatness; but had to work at it, is less well known. The era of the Seven Years War bore witness to the formative years of his character and provides us with a portrait of a young man still trying to make a name and a fortune. That this quest for self improvement was so intimately bound up in the North American theater of the Seven Years War makes the details of Washington's early years only that much more fascinating.

By way of background, some of the more significant aspects of his early years bear mentioning. He was the oldest son of the second marriage of his father, Augustine Washington. His father having died early, he regarded his older half-brother, Lawrence, almost as a surrogate and remained close to him until Lawrence's death from tuberculosis. Mount Vernon, named after Admiral Vernon under whom Lawrence had served during the War of Jenkins' Ear, belonged to Lawrence, who, as the eldest of Augustus' sons, bore the right of inheritance. Since Lawrence left behind only a sickly daughter and equally feeble wife, George would eventually become the heir to the family fortune.

Washington's education was haphazard at best. Driven by his less than ideal prospects for a prosperous future, he worked steadily at self-improvement. He was plagued by a terrible temper for which he compensated by affecting a distant and at times icy comportment. He was an assiduous reader and would eventually write a book on ettiquette. After being talked out of an initial desire to go to sea, he acquired an interest in things military and soon offered his services to the colony of Virginia. He saw such service as a stepping stone to eventually acquiring the King's commission in the British army.

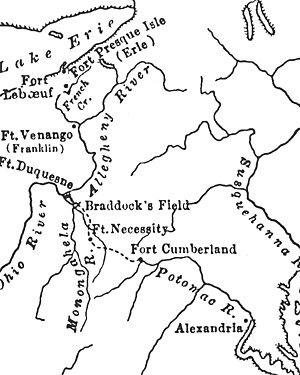

In the meanwhile, using surveying equipment that used to be his father's, Washington was able to find employment by surveying land. This helped fuel his own desire to acquire territory and led to his interest in the Ohio Company. This was a group of land speculators that had formed in the colony of Virginia in 1749. Among its members was none other than Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia, a man whose favor Washington assiduously and continuously courted. The company claimed some 200,000 acres of land in the Ohio Valley west of the Allegheny Mountains as its own. To secure its claim, they intended to build a series of forts, beginning with one at Wills Creek (Cumberland, Maryland) and extending well into the Ohio country. Although Washington himself was not a member of the Ohio Company, he shared with them a common desire for land in what is now eastern Pennsylvania (the territory was then claimed by both Pennsylvania and Virginia).

The French were aware of British designs on territory that they also claimed. As early as 1749, Celeron de Blainville had led a military expedition in a great circle throughout the area asserting French control and trying to overawe the indigenous peoples into pledging their loyalty. The pressure was ratcheted up a notch in 1752, when Charles Langlade led a mixed force of 240 French and Indian allies in an attack on the English trading post at Pickawillany (modern Piqua, Ohio). The English traders were sent packing and the pro-British village leader, Memeskia, was killed, boiled, and ceremonially eaten. Clearly tensions were on the rise.

In 1753, Dinwiddie sent Washington to the Ohio country as a British emissary. His task was to deliver a message to the French to cease their encroachments on land claimed by Virginia. He was accompanied by a small party of men that included the frontiersman, Christopher Gist, interpreter Jacob von Braam, and several Mingo Indians led by Tanacharisson, also known by the English as the Half-King. On the way, he paused briefly where the Monongahela and Allagheny Rivers converge to form the Ohio River, known as the Forks of the Ohio, and noted that this would be a good place to build a fort. He then continued his journey northwards. On November 25th, at Fort Le Beouf, Washington delivered the letter to the commanding officer, Captain Legardeur de Saint-Pierre. After receiving Dinwiddie's letter, Saint-Pierre and his officers wined and dined Washington and his men. As the wine took over their judgement, the Frenchmen informed him that they were there to stay and did not feel obliged to obey the summons. [165]

After an eventful and arduous journey in which he twice nearly lost his life, Washington returned to Virginia and informed Dinwiddie that the French wouldn't budge. [166]

Neither however would Dinwiddie, who decided that the skillful application of force was now required. He immediately assembled a force of volunteers. Capt. William Trent, seconded by Ensign Ward, was ordered to recruit a force of 100 men and march to the Ohio to construct a fort at the Forks, located at the spot Washington had earlier visited.

[167]

Washington, now serving as the adjutant of the Northern Neck, was to raise 50 men from Frederick County and 50 men from Augusta County. Dinwiddie gave him these orders:

Thus were plans set in motion to remove this affront to the sovereignty and colonial authority of Virginia.

In the event, the men of Frederick and Augusta counties proved reticent to risk their necks in any wilderness adventure and Washington soon returned empty handed. To sweeten the pot, Dinwiddie was obliged to issue a proclamation on the 19th of February stating that 200,000 acres on the east side of the Ohio would be distributed among the volunteers. This had little effect. At length, after the House of Burgesses had voted £10,000 for defensive measures, he decided to use a portion of that money to raise up six fifty-man companies of volunteers who would comprise the Virginia regiment.

Washington's ears pricked up at the thought of a military command. He soon wrote to Dinwiddie:

"In a conversation with you at Green Spring, you gave me some room to hope for a commission above that of major, and to be ranked among the chief officers of this expedition. The command of the whole forces is what I neither look for, expect, nor desire; for I must be impartial enough to confess, it is a charge too great for my youth and inexperience to be entrusted with ... But if I could entertain hopes, that you thought me worthy of the post of lieutenant-colonel, and would favor me so far as to mention it at the appointment of officers, I could not but entertain a true sense of the kindness."

His hopes were soon rewarded with a commission as lieutenant colonel. A portly schoolteacher and man of letters named Joshua Fry was to be the colonel of the newly formed regiment. [168]

While the regiment was still being recruited and supplied, Dinwiddie got word that the French were advancing faster than expected, so he ordered the lieutenant colonel to march ahead with what forces he had with him. Fry would join him later. Thus Washington left Winchester, Virginia, on April 18th 1754 and headed for Wills Creek. From there he was to build a military road extending into the Ohio Valley.

Not Going Well

While all this was happening, things were not going so well for Trent's men at Fort Ohio. On the 17th of April, while Trent was temporarily away leaving Ensign Ward in command, between 500 and 1000 French colonial troops under Captain Contrecoeur arrived in canoes in the vicinity of the partially constructed fort. The French landed, formed up, advanced on the fort, and demanded that the English leave. When the French refused a parley, Ward, with only forty-one men available, had no other choice and readily agreed to Contrecoeur's proposal. Among Ward's people was Tanacharisson, the Half-King. He was humiliated and enraged by this forcible eviction and, in the midst of a serious temper tantrum, vowed revenge. He was to have his revenge sooner than anyone thought.

For three weeks the men toiled, building a road as they advanced. During this time Washington continued to correspond with Tanacharisson, assuring him of his cooperation lest his Indian ally's loyalty should flag. Oddly enough, in his correspondence with Governor Dinwiddie, he complained less about the arduous nature of his task and the lack of forthcoming reinforcements from Virginia than he did about his pay and that of his men. Colonial troops were paid less than those on the regular establishment. Washington knew this when he took his assignment, yet, almost as soon as he was in the field, directed numerous complaints to his exasperated superior.

On May 24th, Washington arrived at a clearing known as Great Meadows located about half way between Will's Creek and Redstone Creek. Here he had his men establish a temporary camp. In one of his letters to Dinwiddie, Washington described it as "...a charming field for an encounter. [169]

In fact, it was simply one of the few open areas where the horses could find some muchneeded forage. Beyond that, it was an oblong patch of low ground some two miles long and two to three hundred yards wide. The encampment was within easy musket shot of a nearby woods. Washington would learn soon enough how charming a field it was.

Two runners dispatched by Tanacharisson soon brought the news of the approaching French to Washington. Then on May 27th, Christopher Gist came to report that his small plantation located thirteen miles away had been visited by fifty French soldiers under an officer named La Force. He reported that they were in an "ugly mood" and that it was only with difficulty that two Indian guards dissuaded them from killing his cow and smashing up his property. He also reported that the French were within five miles of Washington's camp. At once Washington sent Captain Hog with seventy-five men to look for the French.

At 9 P.M. the same day, a Mingo messenger named Silverheels brought word that the French were camped in a ravine along Chestnut Ridge, 7 1/2 miles from Great Meadows. Washington set out with forty men under Captains Stephen and van Braam and made his way to Tanacharisson's camp. In the misty and sodden dawn of the 28th, they at last arrived, after marching and blundering all night through a driving rain. Washington conferred with his ally and it was agreed that he and his men would accompany Washington's force. Then, accompanied by a dozen Indians, the men moved north along the Nemocolin Trail to the French camp.

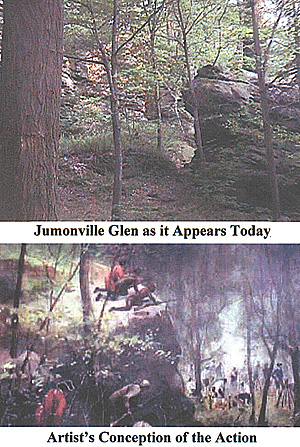

Joseph Coulon de Villiers, Sieur de Jumonville was in charge of the French force. He had been sent by Contrecoeur to scout the position of the colonial troops and divine their intentions. His mission was as much diplomatic as it was military. He was carrying on his person a letter not unlike the one carried by Washington the previous year, except this time requesting that the English depart from French territory. For reasons not fully explained, the French had made their camp for the night in a ravine using rock overhangs and bark leantoos for protection for themselves and their equipment. In the early hours of dawn they were busy making breakfast and no guards were posted.

Washington divided his force in half. One group was under the command of Captain Stephen and the other under his own control. Tanacharisson and his warriors placed themselves at the far end of the ravine. As Stephen deployed his men along the left edge of the glen, Washington posted his on the right, so that a semi-circle was formed around the oblivious French. There are various interpretations as to what happened next.

It appears likely that the French spotted Washington's men as they maneuvered into position and shouted the alarm. A shot was heard, then more shots and shouting as the French ran for their weapons. In the exchange of fire that followed, Washington's took most of the French volley resulting in the loss of on man killed and two or three wounded. The French, seeing their escape cut off by Tanacharisson's men, lay down their arms. At this point the various accounts diverge radically.

Washington's own version, written in a letter to Dinwiddie, appears only after a lengthy discourse on the subject of his pay and status as commander of the Virginians. It is a model of brevity:

"When we came to the Half King I council'd with him, and got his assent to go hand in hand and strike the French, accordingly, himself, Monacatoocha, and a few other Indians set out with us, and when we came to the place where the Tracts [170] were, the Half King sent Two Indians to follow their Tract and discover their lodgment which they did abt half a mile from the Road in a very obscure place surrounded with Rocks. I thereupon in conjunction with the Half King and Monacatoocha, found a disposition to attack them on all sides, which we accordingly did and after an Engagement of abt 15 Minutes we killd 10, wounded one and took 21 prisoners, amongst those that were killd was Monsieur de Jumonville the Commander, Principl Officers taken is Monsieur Druillong and Monsr Laforc, who your Honour has often heard me speak of as a bold Enterprising Man, and a person of gt subtilty and cunning with these are two cadets..." [171]

By his own admission, Washington approached the French with the intent of attacking them. His actual description of the fight itself is very sketchy. He doesn't indicate who fired first or whether any attempt was made to invite the French to surrender first. Even his description of his own casualties is lacking clarity in that later in the letter he acknowleges one man killed and "...two or three wounded..." Wouldn't he know how many of his own men were wounded? The fact that his spelling and punctuation suffer and the narrative turns into one long run-on sentence at this point in the letter is indicative of a writer hastily glossing over an episode that he would rather not discuss. What actually happened here?

Washington's diary entry gives us little more to work with:

"...we formed ourselves for an Engagement, marching one after the other, in the Indian Manner: We were advanced pretty near to them, as we thought, when they discovered us; whereupon I ordered my company to fire; mine was supported by that of Mr. Wag[gonnJer's, and my Company and his received the whole fire of the French, during the greatest Part of the Action, which only lasted a Quarter of an Hour, before the Enemy was routed.

We killed Mr. de Jumonville, the commander of that Party, as also nine others; we wounded one, and made Twenty-one Prisoners, among whom were M. la Force, M. Drouillon, and two Cadets. The Indians scalped the Dead, and took away the most Part of their Arms..." [172]

Again, it appears that the Virginians initiated the action without warning or giving their opponents the option of stating their purposes.

French Version

A French soldier by the name of Monceau was able to get away and reported the incident to Contrecoeur. Here is his take on the action in a letter to Duquesne of the 2nd of June:

"One of that Party, Monceau by Name, a Canadian, made his Escape and tells us that they had built themselves Cabbins, in a low Bottom, where they sheltered themselves, as it rained hard. About seven o'Clock the next morning, they saw themselves surrounded by the English on one Side and the Indians on the Other. The English gave them two Volleys, but the Indians did not fire. Mr de Jumonville, by his Interpreter, told them to desist, that he had something to tell them. Upon which they ceased firing. Then Mr. de Jumonville ordered the Summons which I had sent them to retire, to be read... The aforesaid Monceau, saw all our Frenchmen coming up close to Mr. de Jumonville, whilst they were reading the Summons, so that they were all in Platoons, between the English and the Indians, during which Time, said Monceau made the best of his Way to us, partly by Land through the Woods, and partly along the River Monaungahela, in a small Canoe. This is all Sir, I could learn from said Monceau." [173]

Contrecoeur was informed by an Indian from Tanacharisson's camp that:

"...Mr. de Jumonville was killed by a Musket-Shot in the Head, whilst they were reading the Summons; and the English would afterwards have all our Men, had not the Indians who were present, by rushing between them and the English, prevented their Design." [174]

Yet another account of the incident appears in the sworn statement of a Private John Shaw of the Virginia regiment. Although he was not a witness to the event, he claimed to have been given these details from other soldiers who had been present. In his statement, Shaw affirmed:

"That an Indian and a White Man having brought Col. Washington Information that a Party of French consisting of five and thirty Men were out [scouting] and lay about six miles off upon which Col. Washington with about forty Men and Capt. Hogg with a party of forty more and the Half King with his Indians consisting of thirteen immediately set out in search of them, but having taken different Roads Col. Washington with his Men and the Indians first came up with them and found them encamped between two Hills[. It] being early in the morning some of them were asleep and some eating, but having heard a Noise they were immediately in great Confusion and betook themselves to their Arms and as this Deponent has heard, one of [the French] fired a Gun upon which Col. Washington gave the Word for all his Men to fire. Several of them being killed, the Rest betook themselves to flight, but our Indians having gone round the French when they saw them immediately fled back to the English and delivered up their Arms desireing Quarter which was accordingly promised them.

Some Time after the Indians came up the Half King took his Tomahawk and split the Head of the French Captain having first asked if he was and Englishman and having been told he was a French Man. He then took out his Brains ans washed his Hands with them and then scalped him. All this he [Shaw] has heard and never heard it contradicted but knows nothing of it from his own Knowledge only he has seen the Bones of the Frenchmen whe were killed in number about 13 or 14 and the Head of one stuck upon a stick for none of them were buried, and he has also heard that one of our Men was killed at that Time." [175]

Shaw's statement is given weight by the testimony of Denis Kaninguen, an alleged deserter from Washington's camp who was more likely an Iroquois from Tanacharisson's people. The following is a transcription of Contrecoeur's description of his account as made by Lieutenant de Lery, who commanded at Fort Presque Isle:

"[July] The 7th, Sunday, at midday, a courier arrived from the Ohio [la Belle Riviere]. Monsieur de Contrecoeur ... sends the attached deposition of an English deserter.

Denis Kaninguen, who deserted from the English army camp yesterday morning, arrived at the camp of Fort Duquesne today, 30 June. He reports that the English army is composed of 430 men, in addition to whom there are about 30 savages...

That Monsieur de Jumonville had been killed by an English detachment which surprised him[. T]hat that officer had gone out to communicate his orders to the English commander[. Notwithstanding the discharge of musket fire that the latter [Washington] had made upon him, he [Washington] intended to read it [the summons Jumonville carried] and had withdrawn himself to his people, whom he had [previously] ordered to fire upon the French[. T]hat Monsieur de Jumonville having been wounded and having fallen[,] Thaninhison [Tanaghrisson], a savage, came up to him and had said, Thou art not yet dead, my father, and struck several hatchet blows with which he killed him. That Monsieur Druillon, ensign and second in command to Monsieur de Jumonville, had been taken [captive] with all of the detachment, which was of thirty men[.] Messieurs de Boucherville and DuSable, cadets, and Laforce, commissary, were among the number of prisoners. [T]hat there were between ten and twelve Canadians killed and that the prisoners had been carried to the city of Virginia [Williamsburg]."

[176]

Thus two of the accounts assign the coup de grace that Jumonville received to Tanacharisson. If Kaninguen spoke Tanacharisson's language, his intrepretation of what the Half-King spoke to Jumonville before sending him across the River Styx makes more sense than Shaw's deposition, which was based on the accounts of two non-Iroquoian speaking Virginians.

For Tanacharisson to have asked "Are you English?" would make little sense in the context; he surely would have been able to tell a French officer from a Virginia militiaman. But the statement "Thou art not yet dead, my father" accords with the diplomatic language spoken between the Iroquois and the French, to whose leaders the Iroquois always referred as Onontio or "Father".

So why was Washington so obtuse in his letter to Dinwiddie? It is probable that he didn't know of the peaceful intentions of the French. When he read the summons that had been sent to him, he was in all likelihood shocked by its ramifications. By attacking and killing people in the midst of a peaceful diplomatic mission, he had unwittingly touched off an international diplomatic incident.

Why didn't he immediately blame Tanacharisson for Jumonville's death and try to shift responsibility for the incident onto the backs of his Indian allies? The fact remained that even if Tanacharisson was responsible for dispatching Jumonville, it was the bullets of the Virginians that had rendered him and his compatriots hors de combat in the first place. Washington was the man in charge of the operation and regardless of whose muskets or tomahawks killed which man the blood was on his hands. Accordingly, Washington in his letter gave but the most minimal account of the battle, citing those most obvious facts and writing with such haste that his syntax fell completely apart in places.

Washington's Defense of His Actions

Confronted with the remonstrances of the prisoners, who declared the peaceful nature of their mission, Washington sought to defend himself later in his letter:

"These Officers pretend that they were coming on an Embassy, but the absurdity of this pretext is too glaring as your Honour will see by the Instructions and summons inclos'd...This with several Reasons induc'd all the Officers to believe that they were sent as spys rather than any thing else, and has occasioned my sending them as prisoners, tho they expected (or at least had some faint hope of being continued as ambassadors) They finding where we were Incamp'd, instead of coming up in a Publick manner sought out one of the most secret Retirements; fitter for a Deserter than an Ambassador to incamp in - s[t]ayed there two or 3 days sent Spies to Reconnoitre our Camp as we are told, tho they deny it - Their whole Body moved back near 2 Miles, sent off two runners to acquaint Contracoeur with our Strength, and where we were Incamp'd &ca now 36 Men wd almost have been a Retinue for a Princely Ambassador, instead of Petit, why did they, if there design's were open stay for so long within 5 Miles of us witht delivering his Ambassy, or acquainting me with it; his waiting cd be with no other design than to get Detachts to enforce the Summons as soon as it was given, they had no occasion to send out Spy's; for the Name of Ambassador is Sacred among all Nations; but it was by the Tract of these Spy's they were discovered' and we got Intilligence of them - They wd not have retird two Miles back witht delivering the Summons and sought a sculking place (which to do them justice was done with gt Judgment) but for some expecial Reason: Besides The Summon's is so insolent, & savour's so much of Gascoigny that if two Men only had come openly to deliver it. It was too great Indulgence to have sent them back." [177]

In his bluster of run-on sentences, Washington was clearly trying to cover his tracks and explain away what could have been regarded as an act of murder from the standpoint of international law. Governor Dinwiddie clearly saw the implications of this act and wasted no time in placing the onus on the Indians, as any quick-witted self-serving bureaucrat might do:

"...this little Skirmish was by the Half-King & their Indians, we were as auxiliaries to them, as my Orders to the Commander of our Forces [were] to be on the Defensive." [178]

Several days later, after he had given the adrenaline a chance to wear off, Washington wrote a brief account of the battle to his brother, John Augustine Washington. In this missive he indulged in a little braggadocio:

"I fortunately escaped without a wound, tho' the right Wing where I stood was exposed to & received all the Enemy's fire and was the part where the man was killed & the rest wounded. I can with truth assure you, I heard Bulletts whistle and believe me there was something charming in the sound." [179]

Doubts concerning the validity of Washington's action nevertheless continued to plague him. Jumonville's second-in-command, Drouillon, claimed that the French were on a diplomatic mission to warn the English to leave the valley. Jumonville in fact carried written instructions from Contrecouer, the commander of Fort Duquesne. Washington in his own defense was to ask why then were his men lurking in the woods only seven miles from the English camp in a "low obscure place?" Was Jumonville intending to spy on Washington or, worse, preparing an ambush? The fact that his men were preparing breakfast without the benefit of sentries would seem to put paid to such a theory. Nevertheless the failure of Jumonville to make any sort of direct contact with Washington prior to the incident would seem to lend credence to the contention that the French were on more of a spying mission than one of diplomacy, in which case they would have been a fair target for military action.

In the event, Washington sent the French prisoners back to Winchester, Virginia, and retired to Great Meadows. There he began construction on a more substantial fortification, which he would name Fort Necessity.

As news of this incident made its way to Europe, the French would use it for diplomatic purposes, claiming, not without some justification, that war was being forced on them. As Walpole would later write: "The volley fired by a young Virginian in the backwoods of America set the world on fire."

Was Washington's volley the first shot of the Seven Years War? Technically not. Before an official state of war was declared between Frence and England, Forts Beausejour and Gaspereau would be captured on the Chignecto Ithsmus, two French warships would be captured by Vice-admiral Boscawen off the Grand Banks, Edward Braddock would be defeated and killed at the Monongahela, Baron Dieskau would be defeated and captured at the battle of Lake George, Fort Bull would be stormed by the French at the Oneida Carry, Minorca would be invaded, and Admiral Byng's fleet defeated. England would not declare war on France until May 18th 1756. Nevertheless it has been argued that Washington's skirmish in the woods of western Pennsylvania put in motion a chain of events that eventually led to the Seven Years War. Or did the chain start with the eviction of Ensign Ward's men from Fort Ohio? Or did it begin with Langlade's attack on Pickwillany? It all depends on where one begins the tale.

In the next installment, we will discuss Washington at Fort Necessity.

Abbot, W. (Ed.). The Papers of George Washington. Vol. I, Charlottesville, 1983.

[165] Saint-Pierre's reply reads as follows: "As to your demand that I should withdraw, I do not believe myself obliged to submit; no matter what your instructions may be I am here by virtue of my General's orders, and I beg you not to doubt for one instant that it is my unshaken resolve to comply

with them with all the exactitude and firmness that one would expect of the best officer." See Eccles, The Canadian Frontier, 1534-1760, page 163.

Part I: George Washington and Jumonville Glen

George Washington and the Seven Years War Part III: Into the Fire: The Braddock Campaign

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web."Having all Things in readiness You are to use all Expedition in proceeding to the Fork of Ohio with the Men under Com'd and there you are to finish and compleat in the best Manner and as soon as You possibly can, the Fort w'ch I expect is there already begun by the Ohio Comp'a. You are to act on the Defensive, but in Case any Attempts are made to obstruct the Works or interrupt our Settlem'ts by any Persons whatsoever You are to restrain all such Offenders, and in Case of resistance to make Prisoners of or kill and destroy them."

On the 20th of April, Washington, who had advanced as far as Will's Creek, received the news of the surrender of Trent's fort at the Forks from Ensign Ward. Washington tried to enlist the aid of Ward's volunteers, but they refused to remain with him because he was unable to pay them the two shillings a day that they had been offered to work at the Forks. As a result, they all deserted. On the 23rd, Washington called together a council of war to decide what to do. It was decided to proceed to the confluence of the Monongahela River and Redstone Creek, where lay a company storehouse. Here they intended to fortify themselves and await the arrival of the rest of the regiment under Colonel Fry.

On the 20th of April, Washington, who had advanced as far as Will's Creek, received the news of the surrender of Trent's fort at the Forks from Ensign Ward. Washington tried to enlist the aid of Ward's volunteers, but they refused to remain with him because he was unable to pay them the two shillings a day that they had been offered to work at the Forks. As a result, they all deserted. On the 23rd, Washington called together a council of war to decide what to do. It was decided to proceed to the confluence of the Monongahela River and Redstone Creek, where lay a company storehouse. Here they intended to fortify themselves and await the arrival of the rest of the regiment under Colonel Fry.

Washington's Version

Washington's Version

Bibliography

Anderson, F. Crucible of War: The Seven Years War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. New York, 2000.

Eccles, W. The Canadian Frontier, 1534-1760, Albuquerque, 1969.

Jennings, F. Empire of Fortune: Crowns, Colonies & Tribes in the Seven Years War in America. New York, 1988.

Lewis, T. For King and Country: The Maturing of George Washington, 1748-1760. New York, 1993.

Washington, G. The Journal of Major George Washington, Williamsburg, 1754 (1959 reprint).

Footnotes

[166] Washington's journal of this trip was soon published and widely read, contributing not a little to his reputation.

[167] This fort came to be known as Fort Ohio during its brief existence.

[168] Fry would later fall from his horse and die of his injuries on the 31st of May, leaving Washington in command of the Virginians.

[169] Washington to Dinwiddie, May 27th 1754, quoted in Abbot, page 105.

[170] This is Washington's misspelling of "tracks."

[171] Washington to Dinwiddie, May 29th 1754, quoted in Abbot, page 110.

[172] Quoted in Anderson, page 53.

[173] Ibid, pages 53-54.

[174] Ibid, page 54.

[175] Ibid, page 55.

[176] Ibid, pages 57-58.

[177] Washington to Dinwiddie, May 29th 1754 Quoted in Abbot, pages 110-111.

[178] Quoted in Abbot, note, pages 114-115.

[179] Quoted in Abbot, page 118. Washington's gasconade did not excape the notice of King George II of England, who commented "He would not say so, if he had been used to hear many."

Part II: Reaping the Whirlwind: Fort Necessity

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. XIII No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by James J. Mitchell

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com