Introduction

Swedish involvement is probably the least known part of the Seven Years War in Europe, barely featured in most general accounts.

Swedish involvement is probably the least known part of the Seven Years War in Europe, barely featured in most general accounts.

At first sight, this seems appropriate given Sweden's stature as the weakest member of the anti-Prussian coalition. The Swedes were barely able to field a single army in Pomerania, scoring no notable successes before withdrawing from the contest prematurely in May 1762.

Closer inspection reveals a more interesting story; not only did the war trigger a major constitutional crisis in Sweden itself, but the Pomeranian campaigns, characterized by amphibious operations and constant skirmishing, provide a contrast to the better known battles and sieges elsewhere.

Swedish Politics

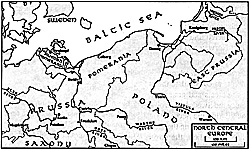

Sweden's involvement and its subsequent military difficulties have to be understood against the background of its general political development. Sweden had once been a major European power, dominating the Baltic Sea by controlling strategic territory along its shoreline. This empire was essentially parasitic since it lacked the indigenous resources to sustain it, relying instead on tapping the wealth of others as it passed through its territory at key trading posts. The desire to prevent a hemorage of potential resources encouraged the seizure of additional land along the southern Baltic shore, as well as protracted and debilitating conflict with Denmark, which controlled Norway and the Sound seaway, giving it access to the North Sea.

Imperial overstretch occured by the mid 17th century and all future attempts to consolidate the empire proved counter-productive, leading to defeats and gradual territorial contraction. By the early 18th century the Swedes were on the defensive and Charles XII's counterattack during the Second Great Northern War (1700 to 1721) ended in disaster, including the king's own death in 1718.

In the absence of a direct male heir, the government divolved to a regency council which not only made peace with the country's external opponents 1719-21, but established a new domestic constitution in 1720. It is this complex settlement that provides the context for Swedish intervention in the SYW.

Though the homeland was relatively invulnerable, there was little the regency could do for the empire, most of which was sacrificed to secure peace. While Russian control over the southeastern Baltic shore was confirmed, Sweden's other opponents were satisfied by concessions in Germany. The Swedish presence there was a legacy of the Thirty Years War and was vital to its prestige as a great power. In addition to conquering over 16,000 square kilometers of strategic north German territory, Sweden emerged as political protector of the German Protestants and a counter-weight to the Catholic Hapsburg emperor.

This position was entrenched in the Peace of Westphalia (1648) when Sweden, along with France, became guarantor of the imperial constitution, giving it the potential for further intervention within the Holy Roman Empire. While these rights were formally retained in the 1719-21 settlement, much of their material basis was removed. Cession of land to Prussia, and especially Hanover, reduced Sweden's German territory by three-quarters, leaving it with only part of western Pomerania (called Vorpommem) and part of Wismar. Meanwhile, its wartime Gemman ally, the Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, was sacnficed to secure peace with Denmark, which now assumed full control of the duke's lands in Schleswig.

These losses were absorbed within Sweden by revising the constitution to the advantage of the nobility, who dominated the representative assembly, or Riksdag. In retum for recognizing the German husband of Charles XII's sister as king, the Riksdag secured control over the governing council, or Senate, along with a veto over key decisions. Swedish politics then became a three- cornered struggle between the crown, which vainly sought to reassert control, and two factions within the Riksdag, which differed over policy.

One group reluctantly accepted their country's much reduced international role and advocated neutrality and free trade as the best route to recovery and prosperity. They were given the derisory name (night) Caps by their opponents, the belligerent (military) Hats, who favoured a war of revenge against Denmark or Russia The Hats got their way in 1741, precipitating a disasterous conflict with Russia that ended with the loss of a further part of Finland two years later.

Defeat exposed the country to foreign influence as Russia, France and Britain each sponsored which ever faction appeared to favour their objectives. Since the king's marriage remained childless, Russia manoeuvered the Swedes into accepting its candidate, Prince Adolf Friedrich von Holstein-Gottorp, as the future monarch. They also approved his marriage to Luise Ulrike, sister of Frederick of Prussia, in 1744.

The Decision for War

The famous international reversal of alliances (in 1754-56) which precipitated the SYW in Europe also triggered a crisis for Sweden which had previously counted on Franco-Russian hostility to retain some freedom of manoeuver. As both of these powers swung behind Austria, Sweden was denied the chance to play them against each other.

Worse, this coincided with domestic problems as Luise Ulrike, Queen since 1751, attempted to restore absolute rule against the opposition of the Hat party, which continued to dominate the Riksdag and the Senate. The Hats discovered that some royalist officers were plotting a coup in 1756 and cracked down, executing 7 ringleaders and forcing others to flee. Though the Riksdag hesitated to bring the Queen to account, the royal family's position was compromised at the critical moment when the country faced the decision between war and peace. With Russia now reinforcing French influence, the Hat leadership in the Senate voted in favor of intervention in August 1757, ignoring the king's protests and those in the Riksdag, which was denied its right to ratify the decision.

The war was seen as a chance to recover those parts of Pomerania which had been ceded to Prussia in 1720. It was also considered essential that Sweden honor its position as guarantor of the imperial constitution or lose its remaining international credit. This was the chief reason why both France and Austria desired a Swedish alliance, since neither placed much weight on its military power. It was essential to Franco-Austrian objectives that the conflict in Germany be portrayed as a police action to punish Frederick for his invasion of Saxony, rather than as a war of aggression to recover Silesia (for Austria).

Not only would the formal support of both guarantors reinforce this interpretation and assist Austria's efforts to mobilize the Germans against Prussia, but Swedish intervention on behalf of Catholic France and Austria would help rally the Protestants by taking the sting out of Frederick's propaganda that is was a religious conflict. Though these reasons explain the surface of events, the underlying factor behind the decision to enter the war was that most of the nobility had still not reconciled themselves to Sweden's international decline and saw the conflict as an opportunity to recover lost glories.

However, the chances of success were already reduced by the controversy surrounding the decision to intervene, particularly as the peasants, who traditionally supported stronger royal rule, were also against involvement and its associated economic repurcussions. These problems were compounded by structural flaws in Sweden's armed forces, which 1eft the country ill-prepared for the contest.

Swedish Military Policy

The nature of Sweden's Ba1tic empire left its armed forces permanently under-resourced for the role they were expected to perform. This worsened after the territorial losses of 1719-21 which deprived part of the army of its recruiting ground, as well as the state of much of its former income. Already in 1719 the new government attempted to reduce military commitments to suit domestic resources by altering the internal structure of the army and navy. This process continued after the defeats of 1741-43, sedously reducing the offensive capability of both arms by 1757.

Earlier forms of conscription were abandoned in favour of a type of militia known as the Indelning for the army and the batmansindelning for the navy. Both varieties involved contracts between the government and various Swedish and Finnish provinces whereby the regional authodties agreed to maintain fixed numbers of soldiers and sailors. These were recruited by voluntary enlistment for service in return for the free use of small farms, while the cavalry were raised from the tenants of the royal domains by a roughly comparable system.

Like the Prussian canton system of recruitment, this method was economical since the soldiers had their own means of subsistence and had the additional advantage that the regiments enjoyed a strong esprit de corps. However, the period of annual training was only three weeks, much shorter than in Piussia, and further limited by the prohibition on manoeuvers while the Riksdag was in session to prevent the possibility of a military coup.

The army's age structure was also adversely affected by the inability to recruit younger men until the existing soldiers completed their service and vacated the farms. Finally, there were constitutional restraints on using these so-called lddelta units for offensive operations, something which added to the political controversy when the Senate sanctioned their deployment in Pomerania

Mobilization of the Indelta could produce 35,000 infantry and cavalry to supplement the 14,000 Swedish and German mercenaries permanently maintained by the central government [see Appendix A]. These included the royal foot guards in Stockholm, as well as the artillery and garrison infantry stationed in the Finnish and Pomeranian fortresses. However, as there were barely sufficient funds to pay the mercenaries even in peacetime, wartime mobilization placed a great strain on the treasury.

Paradoxically, this necessitated precisely the sort of offensive operations for which the army was so ill equipped, since once it started a war, Sweden had to capture land to sustain further military effort. Though France was to provide 11.6 million silver talers in subsidies through 1761, the war cost over 60 million talers, sustained only by ad hoc emergency fiscal measures, triggering an inflationary crisis that lasted into the 19th century.

The diffficulty of reconciling defensive and offensive imperitives was even more pronounced in the navy, which had to act as both barrier to foreign invasion and bridge to the southern Baltic coast. The offensive element was represented by the High Seas Fleet of conventional broadside sailing warships controlled by the Admiralty in the Karlskrona naval base. In terms of size, the fleet was still respectable with a total displacement of 47,000 tonnes in 1756, but most of its vessels were old and in any case, of limited value in a war against Prussia, which had no naval forces and very little merchant marine.

The galley flotilla represented the navy's defensive capacity, equipped with purpose-built shallow draught warships designed to protect Sweden's extended coastline form amphibious assault. [see Appendix B]. The flotilla had been expanded by the military plan of 1747 which favoured the defensive over the offensive, concentrating on fortifying Finland and southern Sweden and constructing a specialist base for the oared vessels at Sveaborg, outside Helsingfors.

A new plan reinforced this trend in 1756, transferring the galley flotilla to the formal command of the army, though in practice it effectively became an independent institution under the control of Augustin Ehrensvard, a politically influential general who ran the Sveaborg base and who was to feature prominently in the war. His appointment was political, intended to strengthen the army which was interested in defending Pomerania and Finland, as opposed to the Admiralty, which favoured a war of revenge against Denmark.

Construction of the new fortresses and bases proved more costly than originally envisioned, necessitating the diversion of scarce resources from an already underfunded army. The chronic lack of money was to prove a serious handicap, compounding problems with the Indelning system. Equipment was in a deplorable state by 1757, especially the muskets which were poorly made and often burst, as many regiments were issued the wrong caliber of ammunition.

One regiment crossed the Pomeranian frontier with only three usable rounds per man while another lacked flints altogether. Cavalry swords were too short and were made from inferior steel, while the uniforms of both arms of service were poorly made, which adversely affected morale and health.

The field force was dependent on resupply from the homeland, something which became almost impossible in the winter when large parts of the Baltic froze over. Swedish Pomerania, covering only 4,400 square kilometers with 100,000 inhabitants, was too small to provide the necessary supplies, while the fortified base at Stralsund (population 11,000) was also cramped. Many of the cavalry and artillery horses died in transport from Sweden, while the others suffered once in Pomerania from insufficient fodder, forcing the army to leave all its heavy artillery behind during the 1761 campaign It was also not until 1759 that it had a bridging train of 20 pontoons, while there was no field hospital before 1760.

Although King Adolf Friedrich had introduced Prussian style drill, training generally remained outdated and hindered by the complex relationship of the officer corps to Swedish politics. Though the army was denied a formal political role, many officers were entitled to vote in the Riksdag as heads of aristocratic families, while each regiment was permitted to send two observers to advise on military questions.

To exclude royal influence, all promotions were strictly according to seniority after 1756. The sale of positions was tolerated, in the absence of an organized pension structure before 1757, to permit elderly officers to fund their retirement.

The infantry regulations of 1751 still endorsed deployment in four ranks as in the age of Charles XII, though this was changed to three ranks in 1760. In the field the infantry formed into battalions of 600 men, divided into four divisions regardless of formal company organization; each subdivided into four (or two for understrength units) platoons. The cavalry received new regulations in 1756, authorizing deployment in three ranks with a 125 man company serving as a squadron in the field.

Though training improved once the war began, politics continually intervened to the detriment of overall efficiency. Many officers favored the Hat Party, but their ardor for conflict soon waned once it had actually started. Some feigned illness as an excuse not to serve. All were aware of the experience of the 1741-43 war when the government executed Generals Buddenbrock and Lewenhaupt as scapegoats for the disaster. Fear of suffering the same fate induced an excessive caution in the current leadership which continually sought specific instructions from Stockholm before taking any action.

More 7YW Swedish Army

-

Swedish Politics and Armed Forces

Appendix A: Swedish Army in 1756

Appendix B: Swedish Navy in 1756

Swedish Mobilization and Strategy

Campaign in Pomerania, 1757-1762

Swedish Jager Units

Prussian Navy vs. the Swedes

Swedish Army Organization

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. X No. 1 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com