[Editor's Note: The following article is an extract from Chrisropher Duffy's The Campaigns of Frederick the Great (2nd Edition) and appears courresy of The Emperor's Press and Christopher Duffy]

There seem to be many reasons why Frederick preferred to

have 'the first army in Europe rather than the worst fleet among the

maritime powers.' The costs of building and manning a navy were

likely to be hideous, and the little which Frederick knew about naval

warfare persuaded him that sea battles were indecisive. He

reckoned that a warship cost the same as a regiment, and that the

regiment was more useful.

There seem to be many reasons why Frederick preferred to

have 'the first army in Europe rather than the worst fleet among the

maritime powers.' The costs of building and manning a navy were

likely to be hideous, and the little which Frederick knew about naval

warfare persuaded him that sea battles were indecisive. He

reckoned that a warship cost the same as a regiment, and that the

regiment was more useful.

Frederick's only port of any size in the Baltic Sea was Stettin, which was almost landlocked, and he believed he must have Danzig as well if he wae to build a standing flotilla of frigates and galleys. Emden came to Frederick with the rest of Ost-Friesland in 1744, when the line of native dukes died out, and gave him his only direct access to the North Sea, in spite of some near-crippling inadequacies - - the port-town stood on an old and badly silted up branch of the Ems, and the territory as a whole was isolated from the core area of the Brandenburg-Prussian state.

These disadvantages were compounded by the hostile attitude of the established maritime powers. The Bengalische Handlungscompagnie (1753) was unable to compete effectively with the British, who confiscated the first of its ships, while a French army occupied Emden in 1757 and captured two of the four vessels of the other commercial enterprise, the Asiatische Handlungscompagnie. In 1765, international trading was revived by a Nutzholtz-Handlungscompagnie However, the scale remained small and although a commercial treaty was concluded between Prussia and the United States on September 10, 1785, the company still owned only eight ships at the time of Frederick's death.

In contrast to his conduct of war on land, Frederick was slow and half-hearted when it came to taking the offensive at sea He lacked any blue water offensive capacity, and he turned instead to war by proxy by licensing British privateers.

As early as May 1757, Captain Maccaffee was cruising for French shipping in the central Mediterranean in a Liverpool privateer called the King of Prussia, which might or might not indicate some kind of authority from Old Fritz. In September 1758, after Sweden had turned against Prussian maritime trade, Frederick issued a number of letters of marque to British privateers. Among the vessels identified are:

- Jacob Merryfield's 12-gun Prinz Ferdinand

- Hugh Caine's 34-gun Lissa (called after Leuthen)

- John Wake's 16-gun Emden (part of a 14 gun privateering fleet of the Guernsey entrepreneurs Nicholas Dobree and Lawrence and Peter Carey)

- Charles Ratcliffe's Lincolnshire Witch (probably hailing from Liverpool).

The victims were primarily French, Spanish, Swedish and Austrian Adriatic merchantmen, and the favourite cruising area was the Mediterranean.

However the privateers were unreliable and uncontrollable, and Frederick lost his desire for further retaliation when it became clear that the enemy alliance had no ambitions to wage a systemic war against Prussian commerce. The French still admitted Prussian trading vessels into their ports and the Russians persuaded the Swedes to join them in signing a Treaty of St. Petersburg (March 20, 1759) which guaranteed unrestricted trade for all ports on the Baltic, including those of Prussia.

Frederick responded in the same year first in the Baltic, then in the North Sea and the Mediterranean, and finally on March 7, 1760 he forbade the issuing of any further letters of marque. The licenses, in any case, brought the state only 11,091 talers, or about one- thousandth of the cost of a land campaign.

Ill Luck

Charles Ratcliffe continued to cruise for Austrian shipping, but on May 5, 1760 he had the ill luck to encounter a merchantman special1y armed by the Trieste entrepreneur, Demetri Voinovich, with the encouragement of Count Kaunitz, the Austrian chancellor. Voinovich battered the Lincolnshire Witch into submission after a hardfought battle, and he hanged Ratcliffe from his own yardarm. 'A cruel fate,' noted Kaunitz, 'but nothing less than he deserved.'

Now that his maritime flank was secure in commercial terms, Frederick's only worry was the problem of defending the Oder River estuary and Stettin against Swedish attack across the lagoon and the Frisches Haff. In July 1757 Frederick had asked the Kammerpradident v. Aschlersleben to confer with experienced seamen about the best means of defending his ports. He himself suggested blockships as an alternative to a flotilla, and it was only on the initiative of the genial, fat and noisy Duke of Brunswick-Bevern that Prussia turned to an active naval defence.

Bevern had been beaten rather badly by the Austrians at Breslau in 1757, which seems to have ruled him out for immediate field command. When he returned from captivity, he was appointed governor of Stettin. Bevern chafed in his enforced idleness and he made up his mind to strike at the only other available enemy, the Swedes, whose flotillas dominated the region of shallows, sandspits, islands and lagoons where the Oder slid into the Baltic.

Aided by Daniel Schultze, a merchent of Stettin, Bevern spent the winter of 1758-59 converting local commercial craft into warships. The non-sailing officers hailed mainly from the Land Battalions, and they were smartly uniformed in blue coats and breeches, and black hats with broad gold lace. The crews were drawn from prime seamen and the troops from the Land Battalions. Prittwitz records that:

-

We officers were most impressed with the flotilla, because we

had never seen anything like it before. When we sailed we

betook ourselves on board, so as to observe the flotilla more

closely. The general effect was by no means unfavourable, for

everything was new and both the sailors and soldiers were well-

dressed. When the sailors appeared on parade, they wore a

white outfit with a red sash around their middles. They sported

felt hats, very much like the hussars, and both sashes and hats

were adorned with the black eagle.

The lagoon flotilla ("Haff-Flotille") first took to the waters of the Oder on April 5, 1759 to the cheers of the sailors and an exchange of salutes between the vessels and the ramparts of Stettin. By September the little navy had been built up into a force of 12 vessels which comprised two types, according to their design and orginal civilian avocations:

-

Galiots were small but beamy craft employed in the

timber trade; they had two masts, with a square sail set on the

mainmast forward, and a gaff sail on the mizzen:

- Koenig v. Preussen: eight 12-pounders, two 6- pounders, four 3 pounders;

- Prinz v. Preussen: eight 12-pounders, two 6- pounders, four 3 pounders;

- Prinz Heinrich: four 12-pounders, six 6-pounders, four 3 pounders;

- Prinz Wilhelm: four 12-pounders, six 6-pounders, four 3 pounders;

- Jupiter: two 12-pounders, six 6-pounders, two 4- pounders;

- Neptun: two 6-pounders, four 4-pounders, six 3- pounders;

- Merkur: two 6-pounders, four 4-pounders, six 3- pounders.

Galeere or Zosekahne were small and broad fishing craft, propelled by two lateen sails and auxiliary oars

Espings or Barkassen were small fast one- or two-masted vessels. There were four of these, named Nos. 1 - 4, each armed with six 3-pounders.

The flotilla was manned by 448 sailors and 162 soldiers, who were expected to do battle with a Swedish armament which was decidedly superior in both experience and force (28 vessels, 402 sailors and 2,882 sailors).

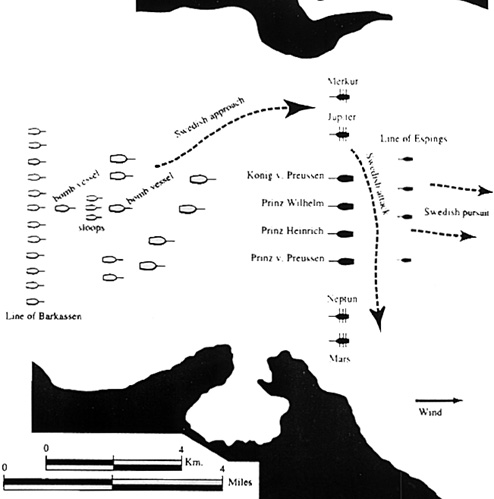

On August 8, 1759 the Swedes penetrated the lagoon of the Frisches Haff by the western channel, the mouth of the Penne (refer to the strategic map on page 20). They were opposed by the new Prussian squadron under the command of Captain Ernst Mattias v. Koller, an officer of the Land Battalions. After a series of manoeuvres and small-scale actions, Koller tried to bar the way to the eastern waters of the Haff ( and thus to the Oder) by anchoring his flotilla in two westward facing lines all the way across the central narrows, from the neighorhood of Neuwarp, on the mainland, to the Woitziger Haken on the island of Wollin in the north.

Two galeere were positioned on either flank of the first line, with four galiots in the middle; the second line comprised the four espings. Both the tactics and the balance between sailors and soldiers are strongly reminiscent of medieval naval warfare.

On the morning of September 10, 1759 the Swedes advanced in three lines before the westerly wind. An artillery duel was prolonged inconclusively for two or three hours, and then the Swedes exploited their advantages in skill and mobility to concentrate an attack by guns, musketry and grenades against the two galleys on the Prussian right (refer to the map), which they captured.

The Prussian center and left had led something of a charmed life ( a lucky shot from the Mars actually sank a Swedish esping ), but now the Swedes proceeded to roll up the first line from the north, talcing the galiots and the remaining galeere one by one. The final phase of the action consisted of an all-out pursuit of the fleeing Prussian second line, which lost one of its four espings.

Altogether the Prussians lost all but three of their flotilla, together with 30 men killed or badly wounded, and 132 rowers and 358 sailors captured. The latter gained a revenge of sorts when 161 prisoners later overpowered the crew of the Swedish galiot Skoldpadde, and brought her into Colberg as a prize.

The little disaster at Neuwarp did not deter the Prussians from rebuilding the Haff Flotilla to a probable strength of 12 vessels. Before hostilities came to an end, a cutting-out expedition succeeded in recapturing the galeere Mars on the night of September 5/6,1761.

Frederick disbanded the flotilla on May 29,1762 and his interest in maritime warfare, never very pronounced, vanished altogether. Whereas he had discussed naval power in the military section of his Political Testament of 1752, he relegated it to the section on trade in the edition of 1768. The only advantages he now sought to gain at the expense of his Baltic neighbors were through financial pressure. The Austrian ambassador reported on May 12, 1765 that:

- The friendship with the King of Poland has cooled

very considerably after he [Frederick] had to pay customs dues

on 2,000 horses he brought from the Ukraine. He has seized on

this incident as justification for setting up a customs post at

Marienwarder [on the Vistula] . All goods which pass by way of

Poland to Danzig and vice versa have to pay dues at 10 percent,

though the merchants who are willing to unload at

Marienwerder are exempt. It is easy to imagine the profit which

the king will derive from this.

More 7YW Swedish Army

-

Swedish Politics and Armed Forces

Appendix A: Swedish Army in 1756

Appendix B: Swedish Navy in 1756

Swedish Mobilization and Strategy

Campaign in Pomerania, 1757-1762

Swedish Jager Units

Prussian Navy vs. the Swedes

Swedish Army Organization

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. X No. 1 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com