Cavalry Combat at La Chaussee

3rd February 1814

The Combat Of La Chaussée

by Andrew Field, UK

| |

In line with Macdonald’s plan to attack on the 3rd, the cavalry of the II Cavalry Corps were mounted at 4 am. [5] However, the heavy cavalry at least did not start their march until much later. [6] No reason is given for this delay but there can be little doubt that it was this, above all else, that spelt doom for the French cavalry. This corps was much reduced in strength and consisted of only two provisional regiments (see ORBAT); one of light cavalry commanded by Genéral de Brigade Domanget and one of heavy cavalry commanded by Colonel Baillencourt. There was a thick fog that did not allow much observation. It could have been because of this that Colonel Baillencourt sent Adjutant-Major Macdermott forward, before reaching La Chaussée, to carry out a reconnaissance of the position that he had been ordered

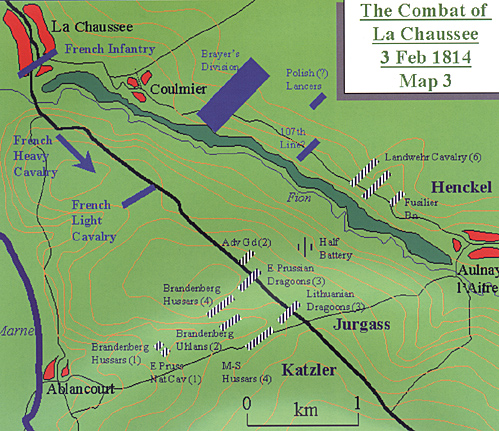

to occupy. This position was on a height to the southeast of the village (see Map 3).

Macdermott found General Exelmans already on this hill who pointed out where the provisional regiment was to take post, as well as the three pieces of artillery which were following it. The general ordered him to return to his regiment quickly in order to hasten its approach. [7]

One is left to wonder if Exelmans was anxious because of the slowness of execution or because he was aware of the proximity of the Prussians. Baillencourt and his provisional regiment arrived at the trot, and, having passed through La Chaussée, climbed the hill, leaving the main road to Vitry to the left, advanced across the plateau towards the place that was indicated.

The light cavalry, who had provided security through the night, were already in position occupying the front line. Baillencourt started to deploy the head of his column to the right and left in order to get the regiment formed into line. [8]

It was at the moment that their heavy cavalry started to deploy onto the heights before the village that the French suddenly found themselves in the presence of 8 squadrons of dragoons belonging to General Jürgass. This general, after having left Saint-Amand at 5.00 am (see Map 2), had followed a back road to the south and joined the main road. Meanwhile, Col Henckel, with his 6 sqns of Landwehr cavalry and a battalion of fusiliers (light infantry), marched from Aulnay-l’Aitre on the paved road which followed the right bank of the River Fion. Katzler’s squadrons had left at the same time from the Bayarne Farm in two echelons; the first of 7 sqns, the second of 6. The infantry advance guard, under the orders of Col von Warburg, followed this cavalry, in order to be able to support it. [9]

Once the advance guard had moved onto the main road, Jürgass stopped his column to give time for Katzler’s cavalry to come up and positioned on his right a half battery of horse artillery in order to fire on the French troops who were off to this flank near Aulnay. Towards 7am, although it was still not completely light, the Prussians observed the French attempting to take position on the southern side of La Chaussée. The calls of their trumpets and the occasional sound of the march of their artillery indicated to the Prussian general that an attack was imminent; as indeed had been ordered by Macdonald. Jürgass, sensing that time was of the essence, immediately deployed his cavalry into two lines preceded by an advance guard.

In the front line, to the right of the main road and close to it, was the advance guard composed of two squadrons. To the left rear of this advance guard and linked with the right of Katzler’s squadrons, was the East Prussian Dragoon Regt, followed by the Lithuanian Dragoons which formed his second line while Katzler, also in two lines, deployed to their left. Four squadrons of the Brandenberg Hussars formed the first line, supported by the two squadrons of Brandenberg Uhlans, and covered to the left by a squadron of Brandenberg Hussars and the squadron of the East Prussian National Cavalry. The Mecklenberg-Strelitz Hussars remained in reserve. [10]

Gen von Jürgass gave the order to fall on the French cavalry at the time when some of it was still trying to deploy and whilst he had the advantage of superior numbers. The

Prussian cavalry therefore quickly formed into line of battle and immediately threw themselves on the French. Because of the rapidity with which it needed to deploy and the difficulties of the ground, the Prussians were unable to wait for all the regiments to come up in order to conduct a charge in line which had been the original intention. The result was that it had to be content with a type of attack in echelon in which the regiments, led by their commanders, deployed into line and charged as soon after each other as possible.

[11]

This seizing of the initiative gave the Prussians an immediate advantage and the Brandenberg Hussars succeeded in breaking the lead French troops; Domanget’s provisional light regiment. One Prussian account claims that the French chose to stand firm and meet the charge with a carbine volley. [12]

The French light cavalry clearly did not wait to receive the impact of the Prussian charge but broke and ran. The French light cavalry swarmed back into their heavy brothers who were still deploying into the second line. The carabinier contingent was swept away with the fugitives. Seeing the impossibility of rallying these troops, Col Baillencourt called on the officers to stop and form up on the hill before La Chaussée, leaving the troops to their flight. As they did this there is no doubt that they were joined by some of his troops and a reasonable body of men were organised. This body of men, combined with the fire of the infantry in the village that opened up at this time, was sufficient to stop the pursuing Prussians. However, the Prussians had brought their horse artillery forward and opened fire, forcing this body of officers to fall back across the bridge into the village.

It was here that chef d’escadron Renaud Fauconnet of the 8th Cuirassiers, the son of Lt Gen Fauconnet, was killed. Col Baillencourt had his horse killed and was wounded in the wrist. He was replaced in command of the heavy provisional regiment by chef d’escadron Coiffier of the 1st Cuirassiers. [13]

The Prussians did not have it all their own way however. On their right, some French cuirassiers held against the East Prussian Dragoons (who presumably did not press their charge home) and on their left, some other cuirassiers had the advantage against the squadron of hussars and the East Prussian National Cavalry of Major von Zastrow.

While their officers imposed upon the Prussians, the French NCOs were able to rally their regiments under cover of the double defile of the small river Fion and La Chaussée. The Prussian charge had nevertheless succeeded. It had managed to break the provisional light regiment, and thrown them back in disorder on the carabiniers and cuirassiers, some of which they had dragged along in their retrograde movement. They had also seized the three French guns before they had had time to unlimber. A body of cuirassiers had attempted to counter attack and retake these by throwing themselves against the Brandenberg Hussars that had not had the time to reform. However, they were forced to retire by the appearance of the E Prussian Dragoons who were coming up in support. [14]

The squadron of volunteer jaeger of the Lithuanian Dragoons then pursued them closely until La Chaussée, where the cuirassiers were able to rally at the exit of the village with the infantry of Molitor’s division.

While the main action took place in front of La Chaussée, on the Prussian right flank, on the far bank of the Fion, Col Henckel claimed to have thrown back some Polish Lancers as far as the height behind La Chaussée and captured their standard. [15]

His fusilier battalion, moving to his left, advanced against La Chaussée itself. By this time however, the French had evacuated the village to take a position further to its

rear where their infantry deployed on some high ground. [16]

The Prussian commanders now faced a dilemma. Before them was the River Fion which was crossed by a small bridge on the edge of La Chaussée. It was quite possible that

some French troops were still in the village and without infantry of their own the crossing of this double defile was a risk. However, for a successful pursuit the pressure must be kept on and it is possible that the French could be seen rallying on the far side of the village preparing to take up the fight. By-passing the village to the north was an option but still required a crossing of the Fion.

In the end, Katzler took his troops through the village and formed up on the far side. Jürgass, with some of his squadrons, preferred to by-pass the village to the north so that he could link up with Col Henckel and to attempt to outflank the French left. His march however, was held up by difficult terrain. [17]

The French had decided not to contest the exits of the village and had started their withdrawal back towards Châlons. Some infantry withdrew along the banks of the Marne as the close country along the river protected them from the attentions of the Prussian cavalry. In the open country on their left, the French infantry withdrew in squares supported by their cavalry and consequently were able to deny the Prussians an opportunity for a successful attack. Katzler followed the French along the main road, while Jürgass pushed along to the north hoping to outflank them.

The French had finally managed to co-ordinate a well-organised withdrawal. The Prussians were forced to watch as their quarry escaped them, though still hoping for an opportunity to show itself. After four kilometers the French force finally reached the village of Pogny on the River Moivre. Whilst this offered them a useful defence line, they would first have to cross the bridge at Les Baraques.

This offered Jürgass a final opportunity; obliged to cross this defile, the French had deployed their cavalry in front of Pogny, in order to cover their retreat and to thus gain the time they needed to cross the river. “I profited from this action”, said Gen Jürgass in his report, “to attempt a new charge: I attacked the enemy in the front with the Lithuanian Dragoons, supported in the second line by those of East Prussia, while Count Henckel’s landwehr cavalry took it from the flank. I threw it back in disorder and pursued it as far as the village; but

the fire of the French skirmishers, which lined the hedges and occupied the houses, stopped the Prussian squadrons and allowed the French cavalry to cross the Moivre and cut the bridge behind it.” [18]

Night was falling and a large French battery established on the right bank of the Moivre had already opened fire when Gen York arrived on the battlefield. He was too late to attempt to force a night crossing of the Moivre as the head of the infantry column had only started to arrive at La Chaussée and they were dropping from fatigue.

[19]

York’s advance guard remained on the banks of this small river, in the positions it held at the end of the fighting. However, he pushed the reserve cavalry and Henckel’s detachment towards Francheville and Dampierre, in order to menace the French left and to gain information on the course and crossings of the Moivre.

[20]

They found these crossings covered by the troopers of III Cavalry Corps. The Prussian 8th Bde occupied La Chaussée and Aulnay, the 7th Bde Saint Amand and the Artillery Reserve, Vitry-le-Brulé. “The results of this cavalry fight, in which, the enemy offered fierce resistance, are brilliant”, wrote York to Schwarzenberg, “seven guns, six caissons, one standard and several hundred men have fallen into our hands. The enemy has suffered considerable losses. Mine are 150 men hors de combat ”. [21]

It is impossible to establish French casualties. Digby Smith’s Napoleon’s Regiments lists one officer killed from the 8th Cuirassiers (Fauconnet), one wounded from the 1st and Col Baillencourt who commanded the provisional heavy cavalry regiment. Only one officer is listed as wounded from the entire provisional light cavalry regiment, suggesting that they broke and ran with little or no contact with the Prussian cavalry.

The 13th (Jérôme Napoléon) Hussars, who were by far the strongest individual regiment on the French side and were not part of the II Cavalry Corps, suffered three wounded officers. However, they are not actually referred to by name in any of the accounts of the fighting so we cannot be sure of what role they took. The only French infantry unit that is recorded as having officer casualties is the 107th Line that was part of Brayer’s division. This division had been ordered to take position facing the village of Aulnay l’Aître on the evening of the 2nd. Digby Smith’s Napoleon’s Regiments records the 107th as having one officer mortally wounded and four others wounded.

As there is no record of any Prussian attacks on infantry and because this level of officer losses suggests a high level of unit casualties, it seems to follow that these could only have been caused by artillery. It could therefore have been the 107th that were the target of Jürgass’s half battery that he placed on his right flank; but this is pure supposition on my part (see Map 3).

Marshal Macdonald had, almost from the beginning of this affair, realised that the poor quality (and low morale) of his cavalry and the indecision of it’s leaders hardly left him with

the chance to gain any advantage. From midday he had reported the loss of La Chaussée to Kellerman and informed him of his retrograde movement on Pogny. [22]

It left the Marshal to concentrate on the defence of Châlons and the retreat of his corps on this town. Before moving to Châlons to confer with Kellerman, he left Sebastiani with the command of the troops between La Chaussée and Pogny and their withdrawal until nightfall. Meanwhile, York was reporting that he would pursue the French if they withdrew the next day or attack them if they stayed in position behind the Moivre. In fact Sebastiani commenced the retreat on Châlons that evening. The move was conducted in good order with II Cavalry Corps providing the rear guard.

By 10pm, the last French troops had left the banks of the Moivre. This position was immediately occupied by the Prussian troops, but they were so exhausted that they contented themselves with observing the direction taken by the retreating French and stopped completely at midnight, in order to take a few hours of rest of which they had great need. The Brandenberg Hussar Regt for example, had set off at 4am, having by-passed Vitry, crossed the Ornain river and joined Gen Katzler’s cavalry on the main road to Châlons a little after 6am; that is to say an hour before the lead squadrons advanced towards La Chaussée. It is not surprising if, that evening, the horses of the regiments that had charged several times during the day, were very tired. [23]

Cavalry Combat at La Chaussee 3rd February 1814

Cavalry Combat at La Chaussee Part 2: 3rd February 1814 by Andrew Field, UK

|