Cavalry Combat at La Chaussee

3rd February 1814

Background and Preliminary Moves

by Andrew Field, UK

| |

1st January 1814. After their catastrophic losses in manpower and prestige during the campaign in Germany the previous year, the meager remains of the French Grande Armée

were stretched thinly along the borders of La Patrie . Barely 70,000 men had survived that campaign and the subsequent retreat into north-east France. Now, while the Emperor tried to raise new armies in Paris, they faced the overwhelming strength of the Armies of Silesia and Bohemia. Both these armies had crossed the natural obstacle of the Rhine and started their march on Paris. With their weak and demoralized forces, Napoleon’s Marshals could do little except fall back before them and pray that the Emperor could deliver a miracle.

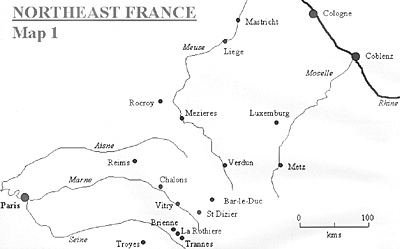

Marshal Macdonald’s XI Corps and the II Cavalry Corps totalled no more than 10,000 men and along with Sebastiani’s V Corps (reduced to a single division of 3,000 men) and the III Cavalry Corps (1,500 men) were responsible sible for guarding a long stretch of the Rhine from Coblenz. On the 10th Jan the Emperor ordered Macdonald to leave garrisons in all the fortresses in his area, to gather up Sebastiani and all the cavalry, and move on the Meuse to threaten the flank of Field Marshal Blücher’s Silesian Army (see Map 1).

Meanwhile, General York commanding the Prussian 1st Corps of the Silesian Army had been left to observe the Moselle fortresses and cover the army’s communications as it advanced into France. On the 21st Jan he was ordered to remain before the fortresses until relieved by Generals Kleist and Langeron and then to reach Bar-le-Duc by the 27th and then Vitry on the 30th (subsequently changed to St Dizier). This would allow him to close up with the rest of the army who were marching to meet up with the Bohemian Army of Field Marshal Schwarzenberg towards Brienne.

On the 25th January, as Napoleon left Paris to join his army, York’s corps stretched from Verdun to Metz leaving him 100 kms away from Blücher who was at Brienne. Blücher realised danger of this separation and ordered York to rejoin him by forced marches. York planned to be at Vitry by the 31st. On the 26th January, Napoleon ordered Macdonald to march on Châlons but on the 27th he was still at Rocroy, a hundred kilometers away. The Emperor was at Châlons with the bulk of his army and was planning to fall on part of Blücher’s army at St Dizier with the aim of then attacking the Prussian’s rear towards Brienne. His attack on St Dizier would place him strategically between Blücher and York.

The French advance on this town started on the 27th but most of Blücher’s forces had left and there was only a skirmish with some Russian cavalry under command of General Lansköi. On the 29th Napoleon caught up with Blücher at Brienne and after a short but stubborn fight forced him to withdraw to the southeast.

On the evening of 31st, the situation was as follows: Macdonald had arrived at Châlons and had pushed some cavalry towards Vitry. York had occupied St Dizier after it was evacuated by the French rear guard without a fight and Napoleon, having forced Blücher to withdraw to Trannes, held a position to the south of Brienne facing him.

Vitry had now assumed a vital importance that was as yet unsuspected by either York or Macdonald. It was the hub of the wheel with spokes that led to Macdonald in Châlons to the northwest, Napoleon at Brienne to the south-west, and York at St Dizier to the east. It offered Macdonald a safe passage to join the Emperor and Napoleon a secure rear. If York

could seize it, it would place both Napoleon and Macdonald in a difficult position.

The battle of Brienne had not been a convincing French victory and Napoleon had failed in his primary objective of preventing the concentration of the armies of Bohemia and

Silesia. On 1st Feb Blücher counter-attacked at La Rothiére and scored a notable, if less than convincing, victory. Napoleon was forced into a fairly precipitous and morale sapping retreat on Troyes to the West. Macdonald’s tardy move South had ensured that his force, however tired and demoralised, was not available to Napoleon at the battle where the Emperor was outnumbered almost two to one.

Whilst Blücher was beating Napoleon at La Rothiére, York advanced on Vitry which was occupied by only 7 to 800 men under command of General Montmarie. Montmarie refused a demand to surrender the town and this refusal was followed by a half-hearted bombardment by York’s field artillery. This had no effect and was soon stopped. A captured

French colonel informed York that Macdonald was at Châlons.

As a result of this information, on the next day (2nd Feb) York moved most of his corps to the northeast of Vitry to Vitry-le-Brûlée (see Map 2), where he was placed to attack either

this town or Macdonald. He pushed his cavalry towards Châlons to try and locate Macdonald. This Marshal ordered Molitor, Exelmans and Brayer, commanding his infantry divisions, to push as far as Vitry, Arrighi (III Cav Corps) to move to La Chaussée with half his cavalry whilst the other half covered the crossings of the Moivre at Francheville, Saint-Jean-sur-Moivre, Coupéville and Le Fresne by that evening. Sebastiani’s V Corps was to go to La Chaussée with the reserve artillery.

Cavalry Combat at La Chaussee 3rd February 1814

Cavalry Combat at La Chaussee Part 2: 3rd February 1814 by Andrew Field, UK

|

The combat at La Chaussée on the 3rd February 1814 is hardly likely to be familiar to many readers. However, it merits examination as it furnishes us with a rare example of an almost exclusively cavalry en- gagement on a scale that can give us an insight to how cavalry really fought rather than the rather abstract, though grand, affairs of Eylau, Aspern-Essling or Lieberwolkwitz. In the first part of this article I will give a little bit of background and a detailed account of the actual engagement. In the second, I would like to explore the reasons why the action turned out the way it did and to try and identify some of the dynamics of cavalry combat that are illustrated by this action.

The combat at La Chaussée on the 3rd February 1814 is hardly likely to be familiar to many readers. However, it merits examination as it furnishes us with a rare example of an almost exclusively cavalry en- gagement on a scale that can give us an insight to how cavalry really fought rather than the rather abstract, though grand, affairs of Eylau, Aspern-Essling or Lieberwolkwitz. In the first part of this article I will give a little bit of background and a detailed account of the actual engagement. In the second, I would like to explore the reasons why the action turned out the way it did and to try and identify some of the dynamics of cavalry combat that are illustrated by this action.