Combat Effectiveness vs. Hoplites

Cavalry are very often depicted fighting hoplites in friezes and on vases, (for example the Defiles relief and the Eleusis relief), the latter often depicted in defeat. This evidence, combined with a close reading of our literary sources, reveals that cavalry often fought hoplites, and that they were frequently successful.

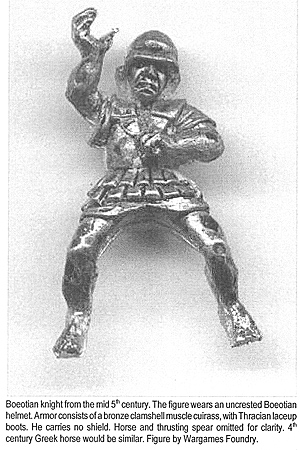

Boeotian knight from the mid 5th century. The figure wears an uncrested Boeotian helmet. Armorconsists of a bronze clamshell muscle cuirass, with Thracian laceup boots. He carries no shield. Horse and thrusting spear omitted for clarity. 4th century Greek horse would be similar. Figure by Wargames Foundry.

This would often be against hoplites who were disordered, either by difficult terrain or by previous fighting, or against a phalanx taken in the flank or rear. But cavalry was also perfectly capable of defeating formed hoplites of much greater numbers than their own by first disordering them and then charging them. If this were not possible, the cavalry could often at least neutralize the hoplites.

It is unlikely that cavalry has ever been able to frontally charge a close formation of spear-armed foot without the latter loosening their formation due to fear of the cavalry or initial casualties from missile fire. However, a skillful use of aggressive skirmishing tactics could disorder the phalanx, or hold great numbers of hoplites at bay.

A good example of this neutralizing of heavy infantry is offered us by the Sicilian Greek cavalry sent by Dionysus I, tyrant of Syracuse, to aid his Spartan allies in 369. "But the little body of cavalry lately arrived from Dionysus spread out in a long thin line, and one at one point and one at another galloped along the front, discharging their missiles as they dashed forward, and when the enemy rushed against them, retired, and again wheeling about, showered another volley. Even while so engaged they would dismount from their horses and take breath; and if their foemen ran up to them while they were so dismounted, in an instant they had leapt on their horses' backs and were in full retreat. Or if, again a party of heavy foot, pursued them some distance from the main body, as soon as they turned to retire, they would press upon them, and discharging volleys of missiles, made terrible work, forcing the whole Theban army to advance and retire, merely to keep pace with the movements of fifty horsemen. After this the Thebans remained only a few more days and then turned back homewards; and the rest likewise to their several homes." (Xen. Hell.7.1.20).

Another example occurred in the 360s. The entire Argive and Arcadian army invaded the small state of Phlious, in the Peloponnese. Its cavalry and a small force of epilektoi (elite infantry paid year-round by the state), assisted by some Athenian cavalry, fell upon the invasion force as it attempted to cross a river, forced it back, and kept the entire army to the high ground.

For proof that cavalry charged and defeated already disordered hoplites Herodotus at Plataea, gives this example: "The victors however pressed on, pursuing and slaying the remnants of the king's army. Meantime, while the flight continued, tidings reached the Greeks who were drawn up round the Mt. Heraeum, and so were left out from the battle, that when the fight was begun, and that Pausanias gaining the victory.

Upon hearing this, they rushed forward without any battle order, the Corinthians wisely taking the upper road across the skirts of Mount Kithaeron and the hills, which led straight to the temple of Demeter; while the Megarians and Phliasians followed the level route through the plain, These last troops had almost reached the enemy, when the Theban horse spied them, and observing their disarray, dispatched against them a company which Asopodorus, the son of Timander, was commander. Asopodorus charged them with such effect that he left 600 of their dead upon the plain, and, pursuing the rest, compelled them to shelter in vicinity of Kithaeron." (Her. 9.69).

In 425, the Corinthians and Athenians fought a tough hoplite engagement to a standstill. It was only due to the charge of their two hundred cavalry that the Athenians emerged victorious, the cavalry then slaying many of the Corinthians in the pursuit (Thuc. 4.43-44).

Eight years earlier, at the battle of Amphipolis, a large group of Athenian hoplites took up a defensive position on a hill after much of their army had been defeated. They faced down several attacks by Brasidas' hoplites, and were only broken when the Chalcidian cavalry and peltastoi (Peltasts) attacked them with missiles and skirmishing tactics (Thuc 5.2,10).

Where he was killed at the battle of Cynoscephalae in 366, the Theban commander, Pelopidas, ordered his cavalry, made up of Thebans and Thessalians, to attack Alexander of Pherae's phalanx. "Between the two annies lay some steep hills about Cynoscephalae which both parties endeavored to take by their foot. Pelopidas commanded his horse, which were good many, to charge that of their enemies; routed and pursued them through the plain. But Alexander meantime took the hills, charging the Thessal ian foot that came later and strove to climb the steep and craggy ascent, killed the foremost, and the others much distressed, could do the enemies no harm.

Pelopidas, observing this, sounded a retreat to his horse, and gave orders that they should charge the enemies that kept the higher ground and he himself, taking his shield, quickly joined those that fought about the hills, advancing to the front, filled his men such courage and alacrity, that their enemies imagined they came with other spirits and other bodies to the fray. They stood two three charges, at first but finding the Thessalians coming on stoutly, aided with the horse, returning from pursuit, finally gave ground, and retreated in order.

Pelopidas, now in procession of the rising ground, perceived that the enemy's army was, though not yet routed, full of disorder and confusion stood and looked about for Alexander, when he saw him on the right wing, encouraging ordering his mercenaries, Pelopidas could contain his anger, but inflamed at the sight of his enemy blindly following his passion, regardless alike of his own life and his command, advanced far before his soldiers, crying challenging the tyrant who did not receive him, but retreating, hid himself amongst his guard.

The foremost of the mercenaries that came to fight hand to hand were driven back by Pelopidas, and some killed; but many at a distance shot through his armor and wounded him, till the Thessalians, for the fear of the result, ran down from the hill to his relief, but found him already slain.

His horse finally came up also, and routed the mercenary phalanx following the pursuit a great way that filled whole country with the slain, which above three thousand." (Plu. Pelopidas, 32). The defeated hoplites in these three instances were no doubt fatigued and disordered from the previous fighting, but were nevertheless defeated by much smaller numbers of hippeis.

There are several examples of cavalry defeating large numbers of hoplites in good formation. A brief survey follows. In 429, as already mentioned earlier, at Spartolos an Athenian expedition, which was composed chiefly of hoplites, was sent to Calcitic. The Chalcidian hoplites were defeated, but their cavalry and light troops beat their Athenian opposite numbers. The Chalcidian cavalry and light-anned infantry then attacked the Athenian main infantry force, forcing the Athenians back with missile fire and skirmishing tactics. Thucydides says the Chalcidian cavalry kept charging in whenever they saw an opportunity and that it was this that contributed most to the rout of the Athenians. The Athenians lost about twenty percent of their men, a large number (Thuc. 2.79). (See Scenario)

In 414, Syracusan cavalry and psiloi (lightly-armed infantry) together put to flight the entire Athenian army's left wing, which in turn caused the defeat of the whole Athenian force. We are not told how they accomplished this but evidently the Athenians would have been mostly made up of hoplites (Thuc. 7.6).

In the 360s, the Thebans, Sicyonians and Pallenes, as well as 2000 mercenaries, invaded Phlious for the second time. The Pallenes and Sicyonians were left to guard the pass into Corinth, while the bulk of the invading army marched towards Phlious. The Phliasian cavalry and epilektoi engaged the enemy's main force, which must have outnumbered it considerably, and prevented the invaders from ravaging their land. When these withdrew, the cavalry of Phlious raced to get to the large enemy force guarding the way into Corinth. The cavalry charged the Pallenes, who were very probably hoplites. These held until the small unit of Phliasian infantry came in support, the Sicyonians and Pallenes then routing.

On another occasion Xenophon reports that the Phliasion cavalry charged the enemy at a full gallop, with their epilektoi charging at the double in support (Hell. 7.2.22). At Mantinae II, the Theban horse, with psiloi support, defeated the Athenian cavalry and then attacked the Athenian phalanx. After a tough fight, they broke the phalanx (Diod. 15.85.7).

We can see that Greek cavalry was at times very effective against hoplites, even those initially in good formation. The hippeis were able to keep large numbers of infantry in check, defeat already disordered hoplites, or even disorder and then defeat the phalanx.

Combat Effectiveness vs. Psiloi and Peltasts

Because psiloi and peltasts were lightly armed and fought in loose formation, cavalry was very effective against them, especially when fighting in open terrain although Xenophon recommends that cavalry use hunting as an opportunity to train for fighting in broken terrain. Accounts of engagements between cavalry and psiloi or peltasts are rare in the sources, no doubt because the light infantry avoided them at all costs! (See Thuc. 4.72 for the defeat of the Athenian psiloi by Theban horse at Megara.) Xenophon mentions one case wherein mercenary peltasts in the pay of Thebes were caught by Olynthian cavalry in the open in 377 and heavily defeated (Xen, Hell. 5.4.54).

Theban cavalry surprised and routed Spartan peltasts in 377, and again in the following year they defeated another force of Spartan peltasts (Xen. Hell. 5.45.39,44-5). At the disaster the Spartans suffered at the hands of Athenian peltasts at Lechaeum in 390, only those Spartans who attached themselves to their cavalry were saved, this indicating that the peltasts were reluctant to pursue those hoplites screened by cavalry.

It is clear from our sources that psiloi and peltasts were very vulnerable to cavalry in the open.

Combat Effectiveness - Auxiliary Troops

The hammipoi did not assist from nearby or in reserve but fought directly amongst the cavalry, as can be seen from the grave-relief in the Louvre wherein a hammipos holds on to the tail of a horse. Hammipoi seem to have been a useful addition to the effectiveness of Greek cavalry; indeed Xenophon says that hippeis aided by hammipoi was much superior to those without. Their presence was no guarantee of success, however, as a small force of Phliasian cavalry unaided by infantry put to flight the entire Argive cavalry and their hammipoi.

We know little of the effectiveness of the Athenian hippotoxitai. We do know that they rode ahead of the hippeis, according to Xenophon's Socrates (Xen. Memorabilia 3.3.1). One would imagine they contributed much to the flexibility of the Athenian cavalry.

Reserves and Flank Attacks

Cavalry, due to their speed, are ideally suited to both flanking maneuvers and to acting as mobile reserves, although the hippeis seem to have usually been deployed either on the wings or at times in front of the main army. In Thucydides'description of the battle of Delium, the Theban cavalry acts as a flanking force, taking the Athenians in the flank by surprise and thus causing their panic and defeat (Thuc. 4.96).

In an Athenian siege of Spartan-held Byzantium in 407, the Spartans made a sortie and were aided by a large force of Persian cavalry and infantry from outside the besiegers' lines under Pharnabazus, the Persian satrap. The battle was a stalemate between these forces until Alcibiades, who had been away, arrived with the cavalry, and a few hoplites, and routed them (Xen. Hell. 1.3.3-7).

During the Spartan campaign against Olynthus in 382, the Spartans kept a reserve of four hundred Elimian cavalry. This reserve saved the Spartans from defeat after the Chalcidian cavalry had defeated the Laconian and Theban cavalry "Being now within a mile or so of the city JOlynthusJ Teleutias came to a halt. The left division, Lacedaernonians was under his personal command, for it suited him to advance a line opposite the gate from which the enemy sallied; the other division of the allies stretched away to the right. The cavalry were distributed thus: the Laconians, Thebans, and all the Macedonians present were posted on the right. With his own division he kept Derdas and his troopers, 400 strong. This he did partly out of genuine admiration for this body of horse, and partly as a mark of courtesy to Derdas, f Tyrant of Emilial so he should not make regret his joining the expedition.

Presently the enemy issued forth and formed in line of battle opposite, under cover of their walls. Their cavalry formed in close order and commenced the attack. Dashing down upon the Laconians and Boeotians they knocked Polycharmus, the Lacedaemonian cavalry general, off his horse, inflicting many wounds on him as he lay on the ground, and cut down others, and finally put to flight the Laconian cavalry on the right wing. The flight of these troopers infected the heavy infantry in close proximity to them, who in turn swerved away; and it looked as if the whole army was about to be worsted, when Derdas at the head of his cavalry dashed straight at the gates of Olynthus, Teleutias supporting him with the troops of his division.

The Olynthian cavalry, now seeing how matters were going, and in dread of finding the gates closed upon them, wheeled round and retired swiftly intothe city. Thus it was that Derdas had his chance to cut down or unhorse man after man as their cavalry ran the gauntlet past him. In the same way, too, the infantry of the Olynthians retreated into their city, though, being to the close to the gates in their case, their loss was trifling.

Teleutias claimed the victory, and a trophy was duly erected, after which he turned his back on Olynthus and devoted himself to felling the fruit-trees. This was the campaign of the summer." (Xen. Hell. 5.2.40). The cavalry of Elis, in the Peloponnese, was kept in reserve at Mantinaea II; they were committed, and then defeated the Theban cavalry, thus saving the Athenian hoplites (Diod. 15.85.7)

Although not used in such ways very frequently, when they were, Greek cavalry performed well as reserves or as flanking forces.

Pursuit and Screening

Although pursuit and post-battle screening are not usually simulated in most war game rules, cavalry are obviously very wellsuited for this, and a brief survey of such actions by Greek cavalry follows: The Theban cavalry pursued the defeated Athenians at Delium, though the fall of night limited the pursuit (Thuc 4.96).

After the Athenians under Alcibiades defeated a large force of Persian cavalry in 409, the Athenian cavalry and a small force of hoplites pursued them until dark (Xen. Hell. 1.2.16). The Spartans defeated the Persian cavalry in 395, and these were pursued by Agesilaos' hippeis, who also captured the Persian camp. At the 'tearless battle' of 368, the Spartans defeated the Arcadians and Argives; the cavalry, with help from Dionysus' Celtic mercenaries, pursued the defeated and cut down many of them.

In 366, after defeating Alexander of Pherae's phalanx, the Theban and Thessalian cavalry of Pelopidas pursued the hoplites for a great distance, causing much loss to the defeated (Plu. Pel. 32).

Aside from being the ideal troops for pursuing a vanquished foe, cavalry was also well-suited to saving defeated friends from pursuit. Xenophon specifically mentions the tactic of attacking a pursuer's flank to halt its pursuit of friends in his Hipparchikos.

In 370, the Mantinaean hoplites were being pursued by mercenary peltasts, when they turned and attacked their pursuers. The peltasts were on the point of being defeated when they were saved by the Phliasian cavalry which threatened the Mantinaeans' rear (Xen. Hell. 6.5.13).

Thucydides says that the Athenians would have suffered very heavily at their defeat at Mantinaea except: "The Tegeans threatened to surround the Athenians. They were in great danger; their men were being hemmed in at one point and were already defeated at another; and but for their cavalry, which did them good service, they would have suffered more than any other part of the army." (Thuc. 5.73).

The Syracusans screened their defeated hoplites with their cavalry from the Athenians after losing the battle in 415 (Thuc. 6.70).

More Ancient Greek Cavalry A Re-Assessment

-

Preface and Introduction

The Greek Hippeis

The North and South

Training

Organization

Equipment

Combat Effectiveness

Conclusion

Back to Strategikon Vol. 1 No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Strategikon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by NMPI

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com