Preface

All dates in this paper are B.C.E. I have made no attempt at consistency with my choice of Latinization of Greek names and words; technical Greek terms appear in italics, and I have provided a translation the first time each term appears.

All dates in this paper are B.C.E. I have made no attempt at consistency with my choice of Latinization of Greek names and words; technical Greek terms appear in italics, and I have provided a translation the first time each term appears.

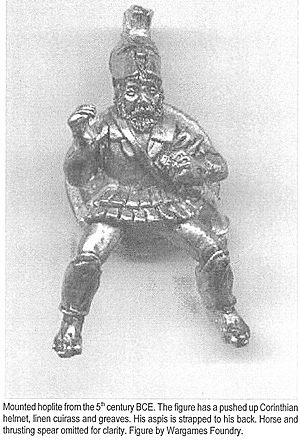

Mounted hoplite from the 5" century BCE. The figure has a pushed up Corinthian helmet, linen cuirass and greaves, His aspis is strapped to his back. Horse and thrusting spear omitted for clarity. Figure by Wargames Foundry.

Similarly, sources appear in full the first time they are mentioned and are thereafter abbreviated. My main primary sources are Xenophon and Thucydides, and to a lesser extent Herodotus, as well as various forensic speeches from the fifth and fourth centuries B.C.E. I have also used later sources, namely Diodorus Siculus and Plutarch.

John Boardman's excellent series of books dealing with Greek art, published by Thames and Hudson, has been of great help. Useful secondary sources on cavalry are I. G. Spence, "The Cavalry of Classical Greece", G. R. Bugh, "The Horsemen of Athens", and also L. J. Worley's, "Hippeis." Other useful works are, "Arms and Armour of the Greeks" by A. M. Snodgrass, and "The Ancient Greeks" by N. K. Sekunda.

Introduction

The ancient Greeks have received short shrift from most war games rules and this is nowhere more evident than with the mounted arm. Indeed Greek cavalry is often poorly regarded outside of the war gaming fraternity; by historians in general. I intend in this paper to challenge this view by analyzing the performance of Greek cavalry in the Classical period, looking at its organization, equipment and training, as well as at the engagements in which Greek cavalry took part during the fifth and fourth centuries.

The reasons for this underestimation of the Greeks held by many modems, and especially war gamers, are several and complex. I do not intend to discuss them in depth here, however a brief enquiry into these perceptions is necessary so that we may look afresh at our subject and make an objective assessment.

One of the chief reasons for this view is historiographical. Contemporary Greek historians frequently leave many details out of their writings, details we today would consider of vital importance. These omissions are partly due to the fact that many such details would be assumed knowledge for the authors' readers, and partly because such particulars were not considered an appropriate topic for writers of literature of the period. Details of the sort that most war gamers revel in were considered fit for bureaucratic lists only, not for history. This paucity of general military detail is exacerbated in the case of cavalry in that our primary sources often neglect or even altogether ignore cavalry.

Due to this lack of military detail, a cursory reading of the main primary sources of the Classical period might leave one with the impression that the military organization of a Greek polis (city-state) was sloppy and amateurish. This is nonsense, though one can understand how such a conclusion would be reached.

A close reading of those same sources, combined with archaeological evidence, as well as other literary evidence (including forensic speeches, comedy, tragedy, and various inscriptions; this last is especially useful as inscriptions often contain the kinds of information not found in literature), gives us a very different picture.

Another contribution to the slanted view of the lack of Greek prowess is that so many war gamers seem very fond of Romans (whether early, medium or late Imperial, Marian, Polybian, Camilian, Eastern, Western) and so are very familiar with Roman history. The Romans, although they borrowed a very sizeable portion of their own culture from the Greeks, thought them to be militarily verging on the incompetent. This is partly natural Roman arrogance, but it is also partly true of the Greeks of that time.

However, the Greeks who with the Romans interacted with during Polybius' time were a very different lot to those of the fifth and fourth centuries B.C.E. Thus many readers swallow the Romans' deflated view of the Greeks of their own time and transpose this back to the Classical period.

More Ancient Greek Cavalry A Re-Assessment

-

Preface and Introduction

The Greek Hippeis

The North and South

Training

Organization

Equipment

Combat Effectiveness

Conclusion

Back to Strategikon Vol. 1 No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Strategikon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by NMPI

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com