Our main source for the actual organization of ancient Greek cavalry is Xenophon, who wrote both a treatise on horsemanship (Peri Hippikes) and a manual written for the commander of the Athenian cavalry (Hipparchikos). This naturally deals with the cavalry of Athens, and we shall use them as our model, but much of what he says can be applied to the mounted troops of other states.

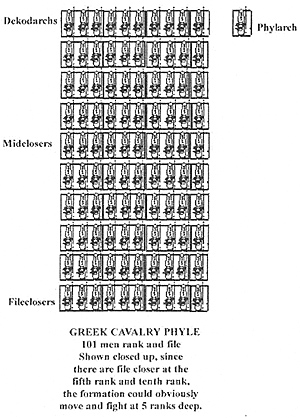

For most of our period, Athens' cavalry was 1000 strong and was led by two hipparchs. The corps was divided further into ten phylai of one hundred, each led by a phylarch. In addition, each file of ten men had an officer at the front, another in the middle, and one at the rear of the file (Xen. Hipp. 2.2, 3). Thus we have a high ratio of officers to troopers, enabling the cavalry to be kept under close control. There was also a unit that Thoukydides referred to as a telos, but it is unclear how large these were (Thuc. 2.22).

The cavalry of most Greek states usually adopted the tetragonal formation, rather similar to a phalanx. Using the Athenians as our model, each phyle deployed in either ten files of ten, or twenty files of five. (See Diagram at right)

The cavalry of most Greek states usually adopted the tetragonal formation, rather similar to a phalanx. Using the Athenians as our model, each phyle deployed in either ten files of ten, or twenty files of five. (See Diagram at right)

The space between the files would depend on the tactical situation. Other formations could be used. At Mantinaea 11, the Theban cavalry adopted the wedge formation, and the way Xenophon describes this suggests it was not especially innovative. The Thessalian cavalry used a rhomboid formation.

The Athenians built specially designed horse transports so as to be able to have cavalry support for their foreign expeditions. These are first reported in 430 when three hundred cavalry joined an expeditionary force which attacked Spartan territory in the Peloponnese." Before, however, the Peloponnesians had left the plain and moved forward into the coast lands he [Pericles] had begun to equip an expedition of 100 ships against Peloponnesus. When all was ready he put to sea, having on board 4,000 Athenian hoplites and 3 00 cavalry conveyed horse transports which the Athenians then constructed for the first time out of their old ships. (Waterlogged with no speed Ed.)

The Chians and Lesbians joined them with their vessels. The expedition did not actually put to sea until the Peloponnesians had reached the coast lands. Arriving at Epidaurus in Peloponnesus the Athenians devastated most of the country and attacked city, which at one time they were in hopes of taking, but did not succeed. Setting sail again they ravaged the territory of Troezen, Alieis, and Hennione, which are all places on the coast of Peloponnesus.

Again putting off, they came to Prasiae, a small town on the coast of Laconia, ravaged the country, and took and plundered the place. They then returned home and found that the Peloponnesians had also returned and were no longer in Attica." (Thuc. 2.56).

These transports were again used by the Athenians in 425: two hundred hippeis joined an expedition against Corinth (Thuc. 4.42). In 348, three hundred Athenian cavalry in horse-transportsjoined the expedition to break the siege of Olynthos by Philip II (FGrH 328 F 51 in Bugh, 164).

Athens' hippeis were augmented by two separate corps, the hippotoxitai and the hammipoi. The hipppotoxitai were horse-archers. These numbered two hundred men, and they appear to have been present from the 440s until some time in the first half of the fourth century. They were probably not Scythians, as is often thought, but Athenian citizens (Alcibiades the younger served with them in 395 and as his joining them was a form of demotion it is unlikely he was an officer (Lysias, 15.6).

The hippotoxitai were not the same as the three hundred toxitai (archers) which served as a sort of police force in Athens and who were public slaves, probably Scythians (Andokles, 3.5), and which fought as foot archers amongst the hoplites, as shown on a vase in the Berlin Staatliche Museen (see A.M. Snodgrass, "Arms and Armour of the Greeks", Pg.73).

The balance of the evidence is made precarious, though, by a depiction of a cavalry inspection on vase 32 in Berlin, part of which shows a hippotoxites who is certainly no Greek he is dressed in stripped trousers and long sleeves. He has been identified as a Scythian by Spence (The cavalry of Classical Greece), but incorrectly, it seems; the hippotoxites does not wear the distinctive Scythian cap, which can be seen on other vases showing Scythians (for example the vase depicting Scythian toxitai referred to above), and looks identical to depictions which have been positively identified as being of Persians.

Hammippoi were light infantry trained to fight alongside the cavalry. The first mention we have of infantry fighting amongst cavalry is in Herodotus' Histories (Herodoms, The Histories, 7.158). In his description of the force which the tyrant Gelon proposed to send to aid Greece against Xerxes' invasion, he mentions hippodromoi psiloi (almost certainly meaning 'horse-running light infantry' and not 'light cavalry' as in De Selincourt's translation of Herodotus, Penguin Classics, and even in Liddel & Scott's Greek lexicon). The Greeks refused to accept Gelon's aid, as they did not want to give Gelon overall command, which he insisted upon.

The Boeotians had adopted hammippoi by 418 (Thuc. 5.57), and the Spartans were using them by 395 (Plu, Ages. 10.3). By 365, the Athenians had supplemented their basic cavalry force with a corps of hammipoi (Xen, Hipp. 5.13), and the Argives had done the same by the 360's (Xen. Hell, 7.2.4). Their numbers are sometimes unclear, but in the case of the Thebans and of Gelon's troops the ratio of infantry to hippeis was one to one.

By 365 (Xen. Hipp. 1.25), the Athenians had created anew type of cavalry, the prodromoi (front-runners). These were very probably scouts, and a unit of them seems to have been attached to each phyle; alternatively they may have been deployed together in one body. Like the hippotoxitai, they seem to have been of a lower social status than the hippeis (Xen. Hipp. 1.23, 25; Aristotle, Athenaion Politeia, 49. 1).

A mention of the somewhat mysterious hyperetai must be made. The term is usually translated in the Classical period as 'servant' or 'attendant' for example, the hoplites' attendants, or batmen, who carried their shields and generally assisted them were called hyperetai. By the Hellenistic period (from after Alexander to the Roman and Parthian conquest of Greek Asia and Europe) cavalry hyperetai seem to have become officers' aides de camps (Arrian, Tactica, 10.4; 14.4), but it is less clear as to what their role was during the Classical period.

Xenophon's use of the term implies a servant, and yet at times he refers to them in combat. He also recommends that they scout ahead of the main force, and that they be used for the passing on of orders. They were not merely grooms, who also accompanied the cavalry on campaign these are referred to as hippokomoi and Xenophon recommends arming them with lances to give the impression of greater numbers of men in the cavalry force.

Whatever their exact function and nature, it is clear that the hyperetai at times fought and performed reconnaissance duties. They were certainly not included in the numbers of cavalry given in our sources; thus the actual number of horsemen available and present on campaign would have been considerably greater than what our sources would indicate.

Greek cavalry was highly organized, and the hippeis had a large number of officers. Cavalry forces often included direct infantry support, and in the case of Athens, horse-archers, and probably included large numbers of less trained but useful troopers in addition to those the sources mention.

More Ancient Greek Cavalry A Re-Assessment

-

Preface and Introduction

The Greek Hippeis

The North and South

Training

Organization

Equipment

Combat Effectiveness

Conclusion

Back to Strategikon Vol. 1 No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Strategikon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by NMPI

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com