The first thing to bear in mind when looking at Greek cavalry, and indeed most Greek military forces of any kind, is that they were essentially a citizen militia. There was no 'soldier' profession; any citizen (and in some cases other sections of the populace, for example the metiokoi (resident foreigners) in Athens, and the periokoi (dwellers-around) and helots in Sparta) between the ages of about eighteen and sixty could be called up for a campaign or battle.

The first thing to bear in mind when looking at Greek cavalry, and indeed most Greek military forces of any kind, is that they were essentially a citizen militia. There was no 'soldier' profession; any citizen (and in some cases other sections of the populace, for example the metiokoi (resident foreigners) in Athens, and the periokoi (dwellers-around) and helots in Sparta) between the ages of about eighteen and sixty could be called up for a campaign or battle.

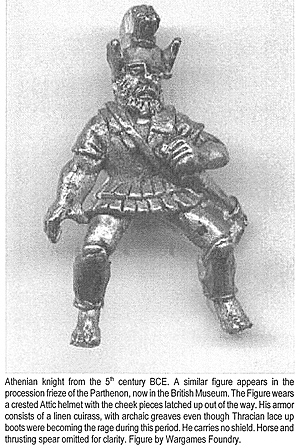

Athenian knight from the 5th century BCE. A similar figure appears in the procession frieze of the Parthenon, now in the British Museum. The Figure wears a crested Attic helmet with the cheek pieces latched up out of the way. His armor consists of a linen cuirass, with archaic greaves even though Thracian lace up boots were becoming the rage during this period. He Games no shield. Horse and thrusting spear omitted for clarity. Figure by Wargames Foundry.

In the case of the cavalry of most Greek states, however, the hippeis were volunteers from within the richer citizen segment. To be considered a member of the upper classes in most states was a measure of wealth, and this would include both the aristocracy of the old families as well as the nouveau riche of the merchant classes. But it would seem that the majority of the cavalry in most poleis were from an aristocratic background, with often the same families contributing members over the entire Classical period. This is certainly true of the hipparchs of Athens (see IG Spence, The Cavalry of Classical Greece, Appendix 5).

Indeed, there was a law in Athens that anyone wishing to join the cavalry had to prove to a committee that he was sufficiently well-off, and that both he and his horse were fit enough (Xen, Oekenomikos 9.15 - Lysias, 14.8). As an exception, Sparta seems to have included periokoi, a group of low social standing, in its cavalry, but the Spartan cavalry was not made up of its elite (See above).

Thus in the hippeis we have a relatively small force of aristocratic volunteers. We can probably extrapolate two main aspects of the cavalry from this. First that it had a high morale due to a strong esprit de corps, and second that it felt in some ways separate from the rest of the army, probably being viewed with some suspicion by the main arm of the army, the hoplites of the phalanx. Aside from individual training, which we can postulate was of a high level in a class so militaristic in its traditions and in one that spent so much of its time and money on horses, we have quite a large body of evidence for unit training, at least in Athens.

There were regular cavalry parades during the numerous festivals. (Xenophon hipparchos 1.20, and Plu. Phokion, "It was the nineteenth day of the month Munychion, on which it was the usage to have a solemn procession of the cavalry in the city (Athens), in honor of Zeus. Phokian's horsemen, as they passed by, some of them threw away their garlands, others stopped, weeping, and cast sorrowful looks towards the prison doors, and all the citizens minds were not absolutely debauched by spite and passion, or who had any humanity left, acknowledged it to have been most impiously done, not, at least, to let that day pass, and the city so be kept pure from death and a execution Phokian's] at the solemn festival."

At the Panathenaia there was a competitive event of javelin-throwing from horseback, as well as numerous horse races. That these festival parades were not simply dignified processions down boulevards is made clear by Xenophon's description of the preparations needed for them; they included mock charges, missile practice and other maneuvers in various formations, including at a full gallop (Xen. Hipp 3.1, 3.7). There also seem to have been regular cavalry processions, called hippades (" Poseidon, God ofthe racing steeds I salute you, you, who delight in their neighing and in the resounding clatter of brass shod hoofs on the paving stones" Aristophenes' Knights")

There was a gate into Athens named the hippades pylai. (This lead out of the city to Eleusis. They was a yearly procession therefrom Athens. Ed.)

There are a significant number of vases depicting cavalry training - throwing javelins from horseback, (See cover), mounting at the run with the aid of a spear, etc. and it was evidently something with which Athenians were familiar. The hippeis were also trained in hoplite warfare. Xenophon mentions that the cavalry of Athens, during the civil war in 404, patrolled the walls as hoplites 'with their shields', and at dawn patrolled on horseback "As to the Thirty, they retired to Eleusis; but the Ten, assisted by the cavalry officers, had enough to do to keep watch over the men in the city, whose anarchy and mutual distrust were rampant. The Knights did not return to quarters at night, but slept out in the Odeum, keeping their horses and shields close beside them; indeed the distrust was so great that from evening onwards they patrolled the walls on foot with their shields, and at break of day mounted their horses, at every moment fearing some sudden attack upon them by the men in Piraeus." (Xen. Hell. 2.4.24),

The Spartan cavalry was also trained to fight on foot. The Spartan cavalry dismounted to fight on foot, with borrowed hoplite shields, in 393 against the Argive phalanx "At that instant Pasimachus, the cavalry general, at the head of a handful of troopers, seeing the Sicyonians hard pressed, made fast the horses of his troopers to the trees, and relieving the Sicyonians of their heavy infantry shields, advanced with his volunteers against the Argives.

The latter, seeing the Sigmas (S for Sicyonia) on the shields and taking them to be Sicyonians, had not the slightest fear. Whereupon, as the story goes, Pasimachus, exclaiming in his broad Doric, "By the twin gods (Castor & Pollax) these Sigmas will cheat you, you Argives," came to close quarters, and in that battle of a handful against a host, was slain himself with all his followers." (Xen. Hell. 4.4.10).

Unlike cavalry of many other times and places, Greek cavalry was very well disciplined both during battle and after, not charging off impetuously or disappearing from the battle due to pursuing a segment of the enemy army. The only occasion on record of where cavalry was overly impetuous was when the Athenian cavalry charged out in scattered groups with very little support against the whole Macedonian army of Philip 11 in Euboia in 348, and was thus defeated.

However, they were rallied from flight and rejoined the battle, completing victory for the Athenians "Plutarch, interpreting this tardiness as a failure in his [Phokian's] courage, fell on alone with the mercenaries, which the Knights perceiving, could not be contained, but issuing also out of the camp, confusedly and in disorder, spurred up to the [Macedonian] enemy. The first who came up were defeated, the rest were put to the rout. Plutarch himself took to flight, and a body of the enemy advanced in the hope of carrying the camp, supposing themselves to have secured the victory.

But by this time, the sacrifice being over, the Athenians within the camp came forward, and falling upon the enemy put them to flight, and killed the greater number as they fled among the entrenchments, while Phokion, ordering his infantry to keep on the watch and rally those who came in from the previous flight, himself, with a body of his best men, engaged the enemy in a sharp and bloody fight, in which all of them behaved with signal courage and gallantry. Thallus, the son of Cineas, and Glaucus of Polymedes, who fought near Phokian, gained the honors of the day. Cleophanes, also, did good service in the battle. Recovering the Knights from their defeat, and with his shouts and encouragement bringing them up to succor the general, who was in danger, he confirmed the victory obtained by the infantry." (Plut. Phok. 12-13).

In conclusion, we can say that the hippeis were more highly trained than their infantry brethren, both individually and by unit. In addition,we can expect thatthey had a high moral, being volunteers and of aristocratic background, although they may well have felt at odds with the rest of the army at times.

More Ancient Greek Cavalry A Re-Assessment

-

Preface and Introduction

The Greek Hippeis

The North and South

Training

Organization

Equipment

Combat Effectiveness

Conclusion

Back to Strategikon Vol. 1 No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Strategikon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by NMPI

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com