It is from similar perspectives that the actions of many of the players in this record of the Second Punic War permit a better understanding of what is happening and why. Given the analysis of C.Flaminius's command at Lake Trasimene, the consular legion was composed of basically two standard legions whether Roman or Roman and allied. This mean the force structure at the River Trebia was composed of approximately two such consular legions and thus four basic legions. While there will be a degree of local supplementation, the Roman and Latin core forces would number 18,000 to 20,000 men under arms, not 40,000. P.C.Scipio encounters Hannibal well prior to the Trebia. "Next day both commanders advanced their troops along the back of the Po which is nearest to the Alps, the Romans having the river on their left and the Carthaginians on their right. On the following day they learned from their foragers that the two armies were almost in contact, wbereuponboth sides pitched camp and remained in their positions. The next morning the two generals led out all their cavalry, while Scipio took his javelin-throwers in addition, and both made a rapid advance across the plain to reconnoiterone another's forces. As each force drew near and saw the clouds of dust that were thrown up by the other's movements they quickly formed themselves into battle order." [Polybios Book III, 65]

The immediate outcome of the story is that Scipio is wounded and withdraws to await the consul T.S.Longus and his legions. P.C.Scipio is not a coward. He is taking a prudent tactical action. He has rightfully ascertained the Carthaginians are superior to his consular anny. It is going to take a larger force to handle this invasion. When the two Romans armies areunited and supplemented to a degree by loyal Celtic formations, T.S.Longus elects to attack. Both Livy and Polybios point out Longus' desire for battle and glory. However, it is unlikely that he would choose to take on a numerically superior force which had already established a viable though limited record of combat. The Romans may have held the Celts in contempt, but this Carthaginian and his army was another matter. Longus' decision to attack at Trebia had to be made with the evaluation of the size enemy before him from Scipio and the belief that man for man, the Roman soldier would prevail.

With the 'treacherous' defection of many Celts among their own ranks [Polybios, Book III, 67], the Romans would not be relying upon them to constitute a significant portion of their army. Given the analysis of the first installment of this article, the ceiling of the Carthaginians would still be no greater than 25,000 and now more likely no greater than 20,000, and possibly fewer.

Certainly the Carthaginians outnumbered C.Flaminus at Lake Trasimene. Hannibal exploits the operational opportunity to destroy the Romans in detail by isolating one major army from another. Even with these defeats, the Roman mind set held that the problem was in the commander or the tactical environment the armies found themselves in rather than the system personified as the legion. The reaction was to appoint a single commander, dictator, Fabius. Fabius particular view on this point was cited in the previous passage from Polybios, Book III, 89. It is the quality of the troops that make Fabius strategy. As recounted in the first installment, he employs the advantages of the fortified position or encampment, terrain, and a relentless hounding of Hannibal's foragers to offset this deficiency. The manpower advantage that Rome exploits constitutes the core of thisarticle. It is strategic. It permits the Republic to deploy multiple legions throughout the Western Mediterranean and sustain them. As with modern logistical operations for deployed forces, this is a major expenditure in manpower. This dedication of manpower to the logistics tail then effects tactical behaviors.

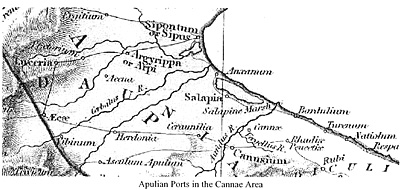

When Hannibal successfully withdraws from the geographical trap of the Falemian Fields, north of Capua and marches east to Gerunium, the Romans are slow to follow. When Hannibal decamps from Gerunium and strikes for Cannae, the Romans, again, are slow to follow. The examination of the Romans logistical system in this article demonstrates the reason. The requirement to provide adequate protection to supply trains demands a significant portion of the Roman field force. A reprise of the sequencing of supply trains reveals that for the entire force on escort duty to return to the main force will take at least five days. This would limitation would not be lost on Hannibal. An extended supply would detract from the number of personnel immediately available for a tactical exploitation. The retention of the supply trains would signal that the Romans were maximizing their strength for such an opportunity. That opportunity culminating at in the battle of Cannae.

The record reports that at Cannae the Carthaginians facing the Romans, force on force, envelope at least one flank of the battle line. Even if the Romans double the depth of their mainline formation, the Carthaginians, without similar additional depth, must still physically overlap the main body of the Romans after routing the Roman cavalry on one flank. A Roman force of considerable size would itself overlap the flanks of the Carthaginian force, making any flank envelopment impossible. That physical deployment consideration places one limit on the probable size of the legions. Predicated upon a Carthaginian force of 25,000, force on force deployment, implies a ceiling of 50,000 for the Roman forces. A combined army of 80,000 which Hans Delbruck defends in his Excursus #2, The Battle of Cannae, History of the Art of War: Within the Framework of Political History - Antiquity, is the 'official' muster accredited to the Romans. Yet this would leave a frontage of 30,000 or 15,000 men, in double depth, which would overlap the Carthaginian front. Envelopment becomes impractical. A penetration and the turning of a line is a more probable tactical consequence. Yet the textual record is clear on this description. If, as demonstrated in the initial installment, that 'numbers' are subject to challenge then the assumptions of Roman strength must also be open to re-examination.

Fabius pursues and shadows the Carthaginians with four legions. The analysis of consular army under C.Flaminius reasonable demonstrates that this is basically only two legions, 9,000 men. The Roman army in Apulia, facing Hannibal, is reinforced the following year with the equivalent of the annual levy of two additional legions bringing the Romans up to approximately 27,000. Variance would be predicated upon casualties and losses during the intervening time as well as relative local manpower. In the Roman case, the need to protect Apri and the other cities of the region from Carthaginian exploitation and to protect supply depots and bases, local allied supplementationwould be fractional, not significant. A rough estimate that the Romans would field around 3 to 4 thousand mounted while the mainline fields 24,000 men. That line being doubled in depth for the battle leaves a frontage for 12,000 men in their units. Since it is the Carthaginian mounted force which throws back the respectiveRoman flanks, both army's center must roughly match in length. This would infer that the Carthaginian mainline would be 12,000. It would be unlikely that the force structure of the Carthaginian army would be half foot and half mounted. Upon that point, the probable ceiling based upon these tactical considerations is 20,000, or even less, for the Carthaginians adjusted down from the 25,000. This permits them to operate well within the movement and supply limitations identified in the first installment.

Fabius pursues and shadows the Carthaginians with four legions. The analysis of consular army under C.Flaminius reasonable demonstrates that this is basically only two legions, 9,000 men. The Roman army in Apulia, facing Hannibal, is reinforced the following year with the equivalent of the annual levy of two additional legions bringing the Romans up to approximately 27,000. Variance would be predicated upon casualties and losses during the intervening time as well as relative local manpower. In the Roman case, the need to protect Apri and the other cities of the region from Carthaginian exploitation and to protect supply depots and bases, local allied supplementationwould be fractional, not significant. A rough estimate that the Romans would field around 3 to 4 thousand mounted while the mainline fields 24,000 men. That line being doubled in depth for the battle leaves a frontage for 12,000 men in their units. Since it is the Carthaginian mounted force which throws back the respectiveRoman flanks, both army's center must roughly match in length. This would infer that the Carthaginian mainline would be 12,000. It would be unlikely that the force structure of the Carthaginian army would be half foot and half mounted. Upon that point, the probable ceiling based upon these tactical considerations is 20,000, or even less, for the Carthaginians adjusted down from the 25,000. This permits them to operate well within the movement and supply limitations identified in the first installment.

At the River Trebia the Romans, at approximately 18,000 with some supplementation, thought they could take the Carthaginians. This was at the time the Carthaginians were at their lowest numbers, suffering from the losses incurred during the transit of the Alps and lacking from vital supplementation from the Cisalpine Celts. There is no documentation or reference to significant reinforcements beyond the Celts by the time of Cannae. The story of the ambush of Rufus Minucius, Master of the Horse, and his relief by Fabius before Gerunium [Poybios, III, 105] shows that the existing Roman forces could at least hold their own. It is with the addition of the next year's levy that not only Gains Terentius Varro, but alsothe Roman Senate believed enough manpower was before the Carthaginians as to achieve victory. [Polybios, III, 107]. A 27,000 (+/-) force does not provide a particular offensive advantage over 25,000 (+/-) force and with the experience of Trebia in their memory, the Romans would certainly seek at least a definite numerical advantage. The bottom line derived from the forgoing analysis is that at Cannae the Romans placed approximately 27,000 men into the field and the Carthaginians around 17,000. These are numbers far below those classically accredited to each antagonist. Here are not armies of 50,000 and 80,000 men. It is an interest note that these figures are much closer to the strengths of the more contemporary army corps of the pre-industrial Napoleonic period. Therein an investigator is likely to find more comparative information to test the validity of data. However, this analysis has been an interesting beginning.

More History of Logistics: Part One

History of Logistics: Part Two

-

Returning to the Scene of the Action

Sustaining an Army

Supply, Size, and Tactics

The Writing of History

Back to Strategikon Vol. 1 No. 3 Table of Contents

Back to Strategikon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by NMPI

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com