Hannibal would regroup his column beyond the Monte Monaco pass along the Vultumus [modem Volturno] River in the vicinity of Allifae. The column would march north along towards Rome through Samniurn then changing direction returning to the eastern slopes of the Apennines and the town of Gerunium [Livy XXII, 18].

Hannibal would regroup his column beyond the Monte Monaco pass along the Vultumus [modem Volturno] River in the vicinity of Allifae. The column would march north along towards Rome through Samniurn then changing direction returning to the eastern slopes of the Apennines and the town of Gerunium [Livy XXII, 18].

Hannibal's Scutari clash with Roman maniples somewhere in central Italy. Figures are Lamming and Garrison. Painting and Photo by SFP

Peter Connolly retraces the most probable route in his work Greece and Rome at War, pages 179-181. An modern map reconnaissance or examination shows that by moving north along the run of the Vulturnus river, a march column would avoid the terrain and slopes of the Monti del Matese terrain feature. Connolly's proposed routing then strikes eastward along natural terrain features and long employed trails and roads to an area just before the eastern slopes of the Apennines well within in distance from Luceria as specified by Polybios, Book III, 100.

In the period follow their triumph at Lake Trasimeme, the Carthaginian army took 10 days to cover 100 miles [Polybios, III, 50]. Simple math shows that the average distance covered daily would be 10 miles. This was over much less challenging terrain than traversing the Apennines. In the march after Trasimeme, the Carthaginians did not have a Roman force shadowing their progress. However, having a measure of Fabius, Hannibal could correctly surmise that the dictator would not expose his own force to either a deliberate battle or meeting engagement. His progress would be unhindered as long as the column would move with attention to its security and order. Such a situation means that the movement would be slow and deliberate. Given these considerations, the Carthaginians would not be in the area of Gerunium until at least 8 days after departing the area around Allitae. The terrain along the route of march is not open or expansive, but hemmed in by the Apennines' topography. Wide ranging foraging is not feasible to eat on the march, so what the soldier carries is what the soldier eats. Here is the beginning of the problems of logistics for the historical record.

One of the more important works of historical analysis on this issue is Donald Engels' Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army. The figures for consumption and portage he employs derived from his sited sources are to be repeated here. Readers seeking greater elaboration on specifics are directed to Engels' work rather than a regurgitation here. The key daily requirements: per man are 3 lb. of grain per day; per horse/donkey are 10 lb. of grain and 10 lb. of fodder.

If these figures are accepted as valid the consumption for a Carthaginian force of 40,000 foot and 10,000 mounted [both rider and horse] would be the equivalent of 250,000 lb. of grain [ 150,000 for the foot and 100,000 for the mounts] and 100,000 lb. of fodder per day. Using 2,000 lb. for a short ton, that would become 125 short ton of grain and 50 short respectively. For an eight day march with full rations that would mean that the Carthaginians would have to haul 1000 tons of grain and 400 tons of fodder. This amount of subsistence would be available having just pillaged and looted the Falemian Fields in Campania. That each soldier would personally add 24 lb. of additional weight to his kit or that each mount would carry and additional 160 lb. for a short duration is feasible. Additionally, for the soldiers, an meat ration from cattle seized during their Campania adventure would substitute for the grain. While the meal on the hoof eliminates some of the need for grain, the cattle also need to be feed and will compete with the mounts and pack animals for fodder along the march route.

Accompanying pack animals carrying food supplies or non-comestibles can lift 200 lb. of materials [Engels]. However, the animal also consumes 20 lb., 10 of grain and 10 of fodder. For an eight day march the pack animal would consume 160 lb. of what it is carrying, leaving only 40 lb. of carriage. From these calculations it can be expected that when the Carthaginian column arrives at the vicinity of Gerunium, it has consumed much of what it started out with.

According to Polybios, Book III, 100, the Carthaginians lay siege to the town, capture it, and put the inhabitants to the sword, careful not to damage its walls or the majority of the housing intending to employ the latter as granaries during the winter. Livy writes, Book XXII, 18, that Geruniurn is abandoned by it inhabitants, with part of its wall collapsed. In either case, the locales are not going to compete for the food supply in the immediate area. Here at Gerunium, twenty-five miles from Luceria, Hannibal has decided to establish his winter quarters. He understands the fundamentals of logistics. He has to feed his army from here for the near future. Relying upon the traditional numbers accredited for the Carthaginian troop strength and the basic numbers of rates of consumption, Hannibal has a major task before him. The daily requirement of 125 short tons of grain and 50 short tons of fodder now become 3750 tons of grain and 1500 tons of fodder per 30 day period just for the combat formations. This does not include the pack animals employed to carry food or non-comestibles. Using ratios employed by Engels for Alexander's army, 1930 animals would be added to the organizational strength numbers. They increase the subsistence needs of the army by 290 tons each of grain and fodder a month. The army will be here for several months.

| Projection of Consumption in Tons | ||

|---|---|---|

| Month | Monthly Consumption [tons] | Accumulative Consumption [tons] |

| 1 | 3790 +1790 | 3790+1790 |

| 2 | 3790 +1790 | 77580 + 3580 |

| 3 | 3790 +1790 | 11370+5370 |

| 4 | 3790 +1790 | 11,555160 7160 |

| 5 | 3790 +1790 | 18950 + 8950 |

| 6 | 3790 +1790 | 22740 +10740 |

| Note: This does not include any calculation for any number of traditional 'camp followers'. | ||

With these levels of consumption, how does Hannibal feed this army at Gerunium? The tomes both of antiquity and modern historians are mute. Logistics is seldom the exciting stuff of history. Without a formal record of the logistics of the belligerents, analysis of the environment and mechanism of subsistence are left as our source for credible findings or conclusions. Environmental considerations include the land and the calendar. The mechanics of subsistence for these annies are the same as for all pre-industrial military formations. The analysis must be constituted of what we know.

Luceria is the nearest prominent town in the immediate region and still exists today. It was founded in 312 B.C.E. as a Roman military colony in a greater strategy to outflank if not encircle the Samnites or their future expansion [Cambridge Ancient History (CAH), Book VIII, The Hellenistic Monarchies and the Rise of Rome, Chapter XVIII, section VII, pg. 601]. In 217 B.C.E. this town has tactical implications to Hannibal's campaign. A strong wall with ample citizens manning the wall are not subject to occupation. The record shows which towns the Carthaginians are able to assault or occupy, Luceria is not one. To use modern terminology, Luceria become a Roman strong point within the area of operation. This become the point of measure from which Carthaginian influence and mobility are seriously hampered or constrained. Luceria lays south to south east of the vicinity of Gerunium. Within a similar span of distance to Luceria's south east is Apri [modem Foggia] which was already subjected to deprivation and foraging at the hand of the Carthaginians in the spring and not a prime source for supplies. Armies dependent upon subsistence which move over routes already worked are armies which starve. Luceria is a physical limit.

The Romans follow in due course after the Carthaginians. Rufus Minucius, Roman Master of the Horse, commands as Fabius has returned to Rome to perform traditional ritualistic functions of his office. Keeping to the high ground to maintain a tactical advantage and to avoid ambushes, the Roman column trails behind the enemy. Minucius is of different inclination to that of Fabius to avoid battle. Once the camp of the Carthaginian is ascertained, the Romans came down from the hills by way of a ridge which slopes down towards Gerunium and establishes their encampment [Polybios, Book III, 101]. This places the Roman route of march towards the Carthaginians as from a northern direction. This places the Carthaginian bivouac between the Romans and the town of Luceria. The Roman camp is the northern limit as Luceria is now the southern limit.

The Carthaginians have operational limitations as well. Foraging forces must remain within a reasonable return distance from their camp. Minucius was able to catch the Carthaginians with too many foragers deployed during the initial days at Gerunium. "Minucius had noticed that large numbers of the Carthaginians were scattered all over the country to carry out these tasks [foraging], and so he chose the hour when the sun was at its height to lead out his forces. When he arrived near the enemy's camp he drew up his heavy infantry in battle order, divided the cavalry and light infantry into several groups, and sent them out to attack the foragers, with orders to take no prisoners. This move placed Hannibal in a difficult position, since he was neither strong enough to accept battle with his main body drawn up outside his camp, nor could be march out to the rescue of those who were scattered about the country.

The Roman who had been sent to hunt down the foraging parties killed large numbers of them, and the troops drawn up front of Hannibal's entrenchment finally became so contemptuous of the enemy that they began to pull down the palisade and came near to storming the whole Carthaginian camp. It was a critical moment for Hannibal, but in spite of this storm of trouble which descended on him he managed to repulse the attackers and by a supreme effort to hold his camp. Finally his situation was relieved by the arrival of Hasdrubal with a force of some 4,000 men, who had fled from the open country where they had been foraging and had taken refuge at the camp near Gerunium."[Polybios, Book III, 102]

Here are some working factors. Minucius begins his operation at noon. He deploys both formed units and cavalry with light infantry task forces to hunt down the scattered foragers. He moves upon the formed Carthaginian element and engages in combat. His task forces have a marked impact upon the foragers of whom the survivors gather at a camp before Gerunium. Some of the foragers then reform and move to the relief of the Carthaginian elements manning a temporary position with palisades under assault. Meanwhile, the Roman task forces continue to find unsupported foragers and progress outward. The small task forces and the foragers, without their forage, can move much faster than the men in the formations. The task forces must stop for their kills, the foragers run for their lives. If the text is to be followed, 4,000 of the foragers make it back to camp, are reformed and march to the relief of the main Carthaginian force. Without a record that any of the fighting continued with the coming of darkness, all these events unfolded in a restricted block of time.

The start of the time line is noon when the Romans move out and three hours for deployment for a force of 20,000 and greater if more are deployed per the Rate of March chart. With the march of both armies from Campania and the establishment of encampments a working parameter of two weeks would have elapsed in the fall which alters the amount of available daylight. Given that the operation would have begun at noon, there would be six hours of daylight and 40 minutes of twilight available. With a deliberate move immediately before the enemy, the legion would keep care of its order rather than its speed. What remains is three to four hours and forty minutes to conduct the fight. Additionally, a good block of this same daylight will also be needed to withdrawal to the secure confines of their cantonment after the engagement. If the Romans move out or in of two gates, it adds at most one hour to the available time period. The task forces must also move out of camp using one or more of the other gates.

Still, multiple legions deploying from separate camps or gates must expend time to align. The Carthaginian foragers would be hit by the task forces concurrent with some of the latter time of the deployment. However, in the same period they need to expend time to rally, reform, and march to the relief of their main force. The 4,000 foragers could not have been far from the camp in order to traverse the distances within these time constraints. The record shows that they came to the relief of the main Carthaginian force well after it was hard pressed in combat.

The operational impact is that foragers can not be deployed far beyond camps or strong points which offer refuge when such tactics are employed. While the forager can move swiftly out to gather, both the action of gathering and hauling any forage greatly reduces even individual mobility. Both pack animals and humans employed for hauling, will move at a much slower sustained rate. Returning to the distance to Luceria, a 25 mile march from it's walls at 4 or 5 miles an hour will take 6 to 5 hours. It will take more than half to two thirds of a day to return to camp with the decreasing period of available daylight late in the year. If the main element of the army or its camp were threatened at this point, the foragers, would not know and would be unable to intervene in this or any other fight.

Upon these considerations, the first element of feeding the army can be based. The area in which foraging may be conducted can be viewed as a circle with the bivouac as the point of origin. The size of the forageable area would be [7ri-2] the traditional formula for the area of a circle. The formula is modified to account for half of the area occupied by the enemy. Terrain, which is undeveloped or unsuitable for forage and subject to overt counter- foraging operations, is accounted for by subtending the section in radians. This produces an angle of 115' rather than 180' [Moorejohn; Mobility and Strategy in the Civil War, Military Affairs, Vol. 24, Summer 1960, pgs 68-77]. Based on the previous analysis of physical and operational limitations the maximum factor of radius, r, is defined as the 25 miles from the Carthaginian position to Luceria. This gives a maximum area available for foraging as 981 square miles. How much forage could be found?

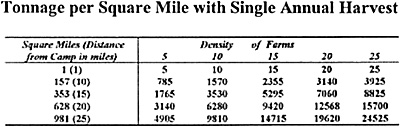

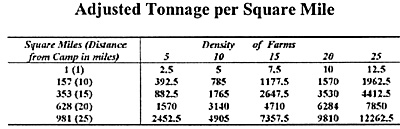

This is still the period of small land holdings and individual homesteads. The vast number of slaves and large capitalistic fanning is still many decades ahead in the expansion of the Roman Republic. This is subsistence fanning, raising sufficient food to feed the fanner and his family. Since we lack specific census status for the land between Geruniurn and Luceria, a model needs to be constructed meeting reasonable expectations. The assumptions of this model are that a non-military adult at a subsistence level could operate over an extended period of time at 80% of the figure previously identified for daily consumption or 2.4 lbs. Two adults would consume 4.8 lbs. Children would consume 1.2 lbs. This gives a working daily consumption figure of 6 lbs per farm unit. A years worth of grain supply would be 2190 lbs or just over 1 short ton. This is then projected with an estimation of the possible number of farms within the forageable area.

When Rome consolidated its control over the peninsula by 260 B.C.E. it encompassed a population of 3 million citizens and fellow Italians within an area of 52,000 square miles [Times Atlas of World History].

This gives an initial figure of roughly 58 persons per square mile. In the cited John Moore study of proto or pre industrial logistics in the American Civil War, the density ratio generated for analyzing the availability of foraging in Napoleonic France is 140 persons per square mile and the American Civil War Confederacy is 17. That this recent colonized area around Luceria would be just less than two and one half as times as dense as Napoleonic France would be exceptional. That it would be significantly higher than the vast tracks of the Confederacy would not. A maximum density of 20 farms per square mile with 2 adults and at least one child gives a population of 50 per square mile. Examination of the photo of the area provided by Peter Connelly, Greece and Rome at Waar, page 181, gives a good view of the immediate locale. These are rolling hills, not flatland.

The chart demonstrates that within the context of these dry projections the Carthaginian army is in a nearly untenable state to be fed. They must gather nearly every available piece of grain within that 25 mile radius, even the area before the wall of Luceria. Very critical to even this consideration is the manner of agriculture employed in the vicinity. If the farmer is using a single annual crop, the projection is valid. If the farmer employs two plantings a year to achieve annual subsistence, one in the spring and one in the fall, only half of the tonnage would be available. The Carthaginians had traversed the area just south of Luceria in the spring. A single harvest system would have only provided minimal subsistence for an army living off the land at that time of year since the local population would have consumed much of their holdings through the winter till the date the belligerent arrived. The reader should recall that the Carthaginians left this area not because of an exhaustion of supplies, rather to implement a strategy of destruction to force Fabius to fight to defend the population and the strength of the Roman alliance. If the chart is adjusted to reflect the two planting cycle, then there is an absolute collapse in the region's ability to generate adequate food.

The chart demonstrates that within the context of these dry projections the Carthaginian army is in a nearly untenable state to be fed. They must gather nearly every available piece of grain within that 25 mile radius, even the area before the wall of Luceria. Very critical to even this consideration is the manner of agriculture employed in the vicinity. If the farmer is using a single annual crop, the projection is valid. If the farmer employs two plantings a year to achieve annual subsistence, one in the spring and one in the fall, only half of the tonnage would be available. The Carthaginians had traversed the area just south of Luceria in the spring. A single harvest system would have only provided minimal subsistence for an army living off the land at that time of year since the local population would have consumed much of their holdings through the winter till the date the belligerent arrived. The reader should recall that the Carthaginians left this area not because of an exhaustion of supplies, rather to implement a strategy of destruction to force Fabius to fight to defend the population and the strength of the Roman alliance. If the chart is adjusted to reflect the two planting cycle, then there is an absolute collapse in the region's ability to generate adequate food.

So far these estimations have focused on grain and

animal fodder. An alternative source of food would be cattle. One of the reasons Hannibal placed his force at risk by extensive foraging before Gerunium was "He was anxious to, according to his original plan, to keep his captured herds alive and also to gamer as much com as possible so as to ensure sufficient supplies to last the whole winter; this was to feed not only his men but also the horses and pack animal, for the cavalry was the arm on which he relied above all others [Polybios, Book III, 101]. The extent of cattle holdings present another problem going back to the Stratagem of the Oxen. If these cattle were part of the booty from the Falerian Fields in Campania, they would have had to been part of the column making its way through the pass around Monte Monaco. A herd of any significant size, as to support the feeding of an army over a month or many months, will impact the operations of that army. The cattle will move 2 miles an hour for any sustained period. As the order of march previously showed, the Spanish and Celts would follow them. Once again, this places the march column at the lower rate of speed and unable to clear the pass within the cited time available. Either the overall numbers of the army must drop significantly to accommodate these herds through the pass or the number of heads of cattle is relatively small. That leave the accumulation of meals on the hoof to the area around Gerunium. If we are to believe Livy, the inhabitants had abandoned their village and made for safer shelter, most likely Luceria. They probably took their movable stock with them significantly reducing the availability of this alternative food supply. If we believe Polybios, the inhabitants who took shelter within the walls of Gerunium probably provided the Carthaginians with some expansion of their long term diet.

So far these estimations have focused on grain and

animal fodder. An alternative source of food would be cattle. One of the reasons Hannibal placed his force at risk by extensive foraging before Gerunium was "He was anxious to, according to his original plan, to keep his captured herds alive and also to gamer as much com as possible so as to ensure sufficient supplies to last the whole winter; this was to feed not only his men but also the horses and pack animal, for the cavalry was the arm on which he relied above all others [Polybios, Book III, 101]. The extent of cattle holdings present another problem going back to the Stratagem of the Oxen. If these cattle were part of the booty from the Falerian Fields in Campania, they would have had to been part of the column making its way through the pass around Monte Monaco. A herd of any significant size, as to support the feeding of an army over a month or many months, will impact the operations of that army. The cattle will move 2 miles an hour for any sustained period. As the order of march previously showed, the Spanish and Celts would follow them. Once again, this places the march column at the lower rate of speed and unable to clear the pass within the cited time available. Either the overall numbers of the army must drop significantly to accommodate these herds through the pass or the number of heads of cattle is relatively small. That leave the accumulation of meals on the hoof to the area around Gerunium. If we are to believe Livy, the inhabitants had abandoned their village and made for safer shelter, most likely Luceria. They probably took their movable stock with them significantly reducing the availability of this alternative food supply. If we believe Polybios, the inhabitants who took shelter within the walls of Gerunium probably provided the Carthaginians with some expansion of their long term diet.

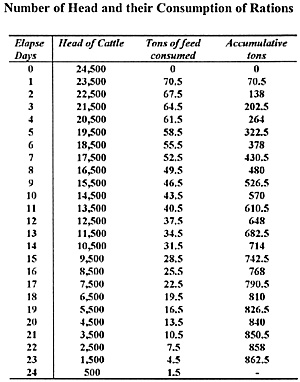

As record shows, cattle did supplement the Carthaginian diet. This alternate form of protein needed to be factored into the overall availability of food to sustain the army. While the cattle add to the calculation of available meals, they also compete with horse and baggage animals for rations and fodder. These are not the present oxen and cows inheritors of generations of modern genetic breeding practices. These creatures would not generate either the weight or the quality of consumable protein which we are familiar with today. However, there is always stew. The subsistence farmer would be happy to have at least one whole healthy cow on the homestead. Generously adding in a few fortunate individuals, employing the 20 farms per square mile calculation as for the grain supply, a factor of 25 usable cattle will be the basis of this estimate.

Using a second and very rough factor that each cow or oxen could feed 50 men, it would require 1,000 head to feed a Carthaginian army of 50,000. The maximum available cattle to displace the gain stock would roughly be 24,525 based upon the number of farms originally estimated in the calculation for grain.. That is an additional 24.5 days towards the food supply. However, the cattle then consume a portion of the fodder and grain for the horse and baggage animals. Failure to feed the cattle will only reduce the food product of animal. For the purpose of this estimate the amount of consumption of feed by each head of cattle is 60% of the rate for horse or baggage animal or 6 lbs of grain and 6 lbs of fodder.

If the cattle are directly consumed to reduce their long term consumption of supplies, they will use 10 days supply of grain. While the cattle lengthen the food supply for roughly 25 days, they also use 10 days of that supply. This extends the Carthaginian overall supplies an additional 15 days.

The ability to trade off grazing with the cattle consuming critical grain and fodder is greatly hampered by the operational situation. The immediate presence of the enemy inhibits open range grazing with a minimum of attendance by herding. The cattle must be guarded adequately. This reduces forces available for foraging at distances and manning the camp defenses. Compounding the problem, once again, is the availability of daylight. Night offers the enemy excellent opportunity for ambush and destruction of poorly defended herds. A cow killed many miles from the camp is not going to be dragged back whole. Rather to recover as much of the usable meat as possible, it would be field butchered and only prime parts would be recovered, significantly reducing the potential food ration displacement a whole animal would provide. At a sustained rate of movement of 2 miles an hour and the ever decreasing availability of daylight as the year moves towards winter solstice, the cattle would not be driven far from the security of the camp in order to graze and to return before darkness. By solstice only 9 hours and 20 minutes of daylight would be available in the latitude. Three hours on the road out means 3 hours on the road back and a little more than 3 hours of grazing. While this is all feasible, it takes away the ability of the horse and baggage animals to graze within those distances for the winter period of their quartering in and around Gerunium. These animals will have to graze much further out as the months drag on placing them at a operational disadvantage was shown in the attack by Minucius. In all the cattle will not provide a significant extension to the time Hannibal has to remain in quarters.

Time is another factor. All the prior consumption calculations were bracketed within a six month period. The working parameters would identify the arrival and departure within that constraint. However, these factors are not definitive. Just when did the Carthaginians occupy and leave Gerunium?

Livy implies that most of the summer had been spent in activity prior to the Carthaginian displacement to the area of Gerunium. Upon following Hannibal back east to Gerunium and encamping, Fabius took his leave to attend to business in Rome. "He [Fabius] urged him [Minucius] not to suppose that nothing was accomplished if the whole summer were spent in eluding and fi7ustrating the enemy..." [Livy, Book XXII, 18]. This means that the great bulk of the summer has been spent not at this location. Operationally it would be judicious for Hannibal to occupy an area just after the local farmers had begun to bring in their crops. This avoids employing troops to conduct a harvest which exposes them to an imprudent tactical compromise. Harvest time would be the period of maximum resource availability. Waiting later in the season would permit the consumption by the fanner and his family of the food stock. Harvest time in the Mediterranean region of Southern Italy is earlier than the common experience of North America or Northern Europe. Harvest would occur in August or September. To minimize the period of quartering at Gerunium for the calculation of time, the fall equinox is the initial date of occupation for this estimation. Six months of supplies would place the end of occupation at spring equinox. A significant element in the logistical consideration is that with the indigenous farmers removed, there would be no planting or breeding in this region for the coming year.

"Throughout the winter and the spring the two armies thus remained encamped opposite one another, and it was only when the season had advanced far enough to allow his supplies to be collected from the years crop* that Hannibal began to move from the camp at Gerunium. By that time it would be in his interest, he considered, to use every means in his power to force the enemy to fight, and so he occupied the citadel of a town named Cannae, where Romans had collected the corn and other supplies from the district around Canusium. The town itself had previously been reduced to ruins, but the capture of the citadel and the stores caused come alarm in the Roman camp." [Polybios, Book III, 107]

*(Planting and harvesting presents the same tactical problem as grazing the cattle. Soldiers assigned over hundreds of square miles to plant and tend crops with an enemy breathing down one's neck is not feasible. The collecting of crops which Polybios refers had to be that which is the object of Hannibal's plan, as it was at Gerunium, to seize the product of others' labors. In this case the storage at the citadel of Cannae which Polybios identifies specifically as a collection point. The amount stored at Carmae has to be of sufficient size to sustain Hannibal's force rather than a one time quick fix of his logistical challenges. The crops being gathered had to be either the annual crop, or in a two crop system, the seasonal crop. However, as previously demonstrated, a two harvest system leaves the Carthaginians inadequate supply of resources upon which to sustain themselves within the parameters of an army of 50,000.)

As an annual crop, the bulk of the food planted around Cannae would not be available for many months beyond spring equinox and much closer to the calendar date in which Hannibal originally displaced to Gerunium from Campania. Even squeezing the growing period to five to six months with planting at spring equinox, means that 50,000 men and their mounts of the Carthaginian army are without food for months. If the date of the harvest is moved earlier, then so is the harvest upon arrival to Gerunium, meaning even more of that potential food resource is consumed by the indigenous people prior to Hannibal's arrival. The brackets of time of planting and harvest at Cannae will match the same bracket for Gerunium. Moving one of the brackets moves the other with a resultant impact gaining at best marginal increases in food resources, not months of supply.

While the condition of the Carthaginian force may not have been optimal, it was not desperate. Hannibal departs Gerunium, marches to Cannae, and successfully assaults the citadel. A map survey shows at a standard rate of 10 miles a day, the army would take at least 5 days on the road just to reach the vicinity of Cannae. This is without stopping to forage in route. To effectively forage would require a halt, collection, consolidation, and reforming. This adds even more days to the march. While a hungry man could be motivated to move from Gerunium with a expectation of future meals elsewhere, animals have no such perception of future returns and are not motivated to move large distances without an instinct derived from generations of migration over known territory. This was not known territory of that kind. The horse and pack animals could not be expected to make such a trek. Yet the record is obvious that Hannibal had significant mounted forces at the impending battle of Cannae. It is reasonable to deduce that the mounts were adequately feed and provisioned.

The use of known data, reasonable estimates of logistics, and the narrative of events do not favorably support the traditional enumeration accredited the Carthaginian forces in 217 and 216 B.C.E. A review of the points elaborated herein demonstrate the vicinity of Gerunium and the tactical imposition of the Roman forces restricted available resources for the Carthaginians. Tonnage available for a concentration of 20 or 25 farms for square mile closes out at 19,620 tons or 24,525 tons respectively.

- Monthly consumption rates of a Carthaginian army of 50,000 with baggage will consume that available limit between 5 to 6 months.

- The record indicates a stay at Gerunium of more than 7 months and more likely between 9 and 10.

- At the end of this period, all arms of the Carthaginians are fully capable to perform an operational march and tactical assault.

- The point of passage of the Carthaginians from the Falernian Fields of Campania demonstrate the length of the column the army would form would not complete the march within the time specified by the record.

While the numbers could be pushed somewhat higher by manipulating some of the factors on which the calculations are based, the strength of the Carthaginian army only include the combatants and no support personnel or 'camp followers'. If these are of any significance in adding to the army's overall population, the resources identified in the core of this work will not be able to support them. Without employing exaggerated factors as incredible rates of march or highly populated and cultivated farmlands which were only recently settled, the ability to generate numbers to support the key interrelated elements to force the underlying but fundamentals of military logistics and movement to match the traditional numbers is not to be found.

Given this analysis, the traditional numbers can not be considered as valid. What this analysis does provide are rational parameters in which the numbers can be reasonably bracketed. If the numbers are literally halved, the food supply around Gerunium provides a year's sustenance. The criticality of the time in spent in quarters at Gerunium is removed. The Carthaginians are now in solid shape to conduct a complete march to their next resource center, Cannae. Finally, the key passage of the army out of Campania in the stratagem of the oxen is feasible to include the redeployment of the Spanish elements. All these conditions and situations are met literally without pushing the edge of the envelope on the data. The actions of Hannibal become framed within a rational context and not one in which his entire effort is continuously dependent upon just making it to the next critical event in the story line. Hannibal is a competent calculating commander not relying upon the whims of chance to conduct his campaign. Regardless of chauvinistic elaboration within the existent tomes, the Carthaginians are as dependent upon logistics limitations as we are today.

This installment of the article has provided the rational data which ascertains a baseline of approximately 25,000 men for Carthaginian army. With this number and an examination of how the to sustain an army not subsisting on foraging, the next installment will examine the Roman forces.

References

The Cambridge Ancient History, Vol. VIII. Rome and The Mediterranean 218-133 B.C., ed Cook, S.A., et al, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1930 [reprint 1978]

Connolly, Peter, Greece and Rome at War, Prentice-Hall, Inc, Englewood, 1981

Delbruck, Hans, History of the Art of War Within the Framework of Political History, Antiquity, Greenwood Press, Westport, 1975

Engels, Donald W., Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1978

Livy, The War with Hannibal, Penguin Books, Middlesex, 1965

Moore, John G, "Mobility and Strategy in the Civil War". Military Affairs, Vol 24, Summer 1960.

Polybius, The Rise of the Roman Empire, Penguin Books, Middlesex, 1981

More History of Logistics: Part One

History of Logistics: Part Two

-

Returning to the Scene of the Action

Sustaining an Army

Supply, Size, and Tactics

The Writing of History

Back to Strategikon Vol. 1 No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Strategikon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by NMPI

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com