Unlike the Carthaginians who must accumulate as much food from the countryside as they can gather, in the case of the Romans who are supplied, the total available tonnage is not important. What are important are the mechanics of the movement of that supply. The preceding analysis made an argument that Fabius would have a force structure of between three and four legions, taking into consideration the losses sustained by G.Servilius in his forces prior to their union with the newly raised legions. In these estimations, the ceiling will be calculated with four full legions. The consumption rates for an army which were employed in the analysis of the Carthaginian army, 3 pounds per day for foot and riders, 20 pounds for mounts and baggage animal are also utilized for the Romans. Four legions will identify 18,000 foot and riders, 1,200 horse, and 720 pack animals. The latter number for this evaluation employs the same ration 1:25 employed as well in the examination of the Carthaginians. Engels identifies the Roman Imperial Legion as having 800 mules. Since that is a period well outside the one under examination and the strategic and operational missions of the legions differ, the first ratio is employed. Adding more pack animals will only increase the managementissue and not the ability to feed the legions. These figures identify a feeding requirement of 92,400 pounds or roughly 46 short tons [2,000 pounds] of subsistence a day. For a single days lift of this food requirement, it would require 460 of the pack animals. That appears to be within the internal capacity of the army, until the mechanics of moving the materials are considered.

Since the source of the provisioning is two to three days away from a port of debarkation, the pack train will be on the road obviously for more than one day. That means the train may have to deliver more than one days provisions in each trip. It also implies with good tactical sense in face of a cunning opponent, that just as one entrenches the main force overnight, then the supply column must as well have shelter against the protagonist. Therefore there would be the equivalent of intermediate staging areas or way stations. The job of the Roman counterpart of the modem commissary or transportation officer would be to coordinate the movementof these trains. Given rates of march [Engels, Appendix 5, Table 7, Notes], it would take a pack train roughly 2 to 3 days to reach the Roman encampment around Gerunium. Engels demonstrates the inverse relationship between the size of the formation and its speed.

Since the source of the provisioning is two to three days away from a port of debarkation, the pack train will be on the road obviously for more than one day. That means the train may have to deliver more than one days provisions in each trip. It also implies with good tactical sense in face of a cunning opponent, that just as one entrenches the main force overnight, then the supply column must as well have shelter against the protagonist. Therefore there would be the equivalent of intermediate staging areas or way stations. The job of the Roman counterpart of the modem commissary or transportation officer would be to coordinate the movementof these trains. Given rates of march [Engels, Appendix 5, Table 7, Notes], it would take a pack train roughly 2 to 3 days to reach the Roman encampment around Gerunium. Engels demonstrates the inverse relationship between the size of the formation and its speed.

The smaller formation will move faster than the full army. It is possible to accomplish the 35 miles in two days rather than the 10 miles a day speed for large formations. What would be the limiting factor is the ability of the pack animals to handle faster pace sustained over several days. Another underlying consideration is the state of the paths or roads being employed. Narrow tracks and terrain can funnel and hamper the speed of supply columns, especially in countermarching circumstances. The latter situation in which two trains try to occupy the same trail, would create delay for one or the other train adding time to the transit. It would also make a tempting target. Delay two trains at the same time and double the impact on the flow of the supplies. It takes time not only to move into a defensive posture, trying to avoid the march column model at Lake Trasimene, but to reorganize and begin again the motion of the train from that defensive mode.

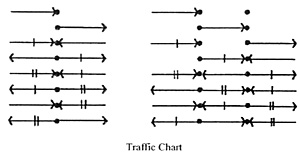

The chart demonstrates the sequencing of trains with one or tw~ intervening overnight stations. The first train has no marking and each subsequent train has identifiable hash mark. In each case the trains optimally deliver every other day. That doubles the amount of daily rations to be carried by the train and the size of that train, from 460 to 920 animals if we are only accounting for food. Fudging the ratio of animals per member of the army, one such train may be covered within reasonable expectation of the legions themselves. When noncomestibles are added, so are additional animals. However, as the chart shows the mechanics require three and probably a fourth such train. Pack animals as well as horse require a day of rest for every five to seven days of march. They develop bleeding sores or physical damage which make them useless until healed [Engels, Appendix 5, Note7]

This means the four deployed legions require 2,760 to 3,280 pack animals to maintain a continuous lift operation. These, in turn, require 36,800 to 47,200 pounds daily of additional food for these animals which then creates the need for 184 to 236 more animals to carry that food. This gets sizable quickly. Just as quickly the size of the train guard grows as well.

The train must be defended in theproximity to the enemy. That means each train must muster an accompanying guard. Each way station must be manned to provide immediate security as well as preventing it being seized and utilized in interdicting the line of supply. Correspondingly, the port must also have sufficient manpower to prevent it from similar interdiction and interruption of operation. To reiterate from the beginning, the depth of an army is the support tail from the tip of a gladius to the point of origin for food, equipment, training, and resourcing. For the compounding of manpower for this operation is just beginning. A supply train of 920 pack animals walked 3 abreast, occupying 8 feet of depth, and maintaining an orderly formation would stretch over 2,453 feet, nearly a half a mile.

The tactical situation of conducting these marches in the near presence of an enemy which has demonstrated the capacity and will to execute effective and quick surprise attacks would place upon the organizers of this resupply operation with a requirement to employ significant march security. The size of the formation to guard the supplytrain must be large enough as to cause the Carthaginians to make an obvious and concerted effort beyond inducing delays in the train's speed with harassing tactics. A movement by a large Carthaginian contingent should induce the activation of large portion of the Roman forces before them countering the attempt to overwhelm the supply train. Given the logistical ability of the Romans, if the Carthaginians move in bulk to sit astride this supply line, it would open up an alternate line to Luceria and Apri. The Carthaginians would in turn be exposing their winter supplies at Gerunium with a markedly reduced covering force. To trade two days of the Roman's supply for most of theirs is not a wise tradeoff. It is with these tactical considerations that a working estimate of a formationequal to the size of thesupply trainbe employed. Using the first chart as a basis of extrapolation, a half a mile of escort foot would take approximately 1071 personnel. If a Roman maniple is constituted with 160 men, the guard would take between 6 to 7 units. Certainly a good representation of the mounted turmae of the legions would also be employed considering the cavalry superiority of the Carthaginians. Expanding this formation for three to four trains quickly compounds the forcerequirement to the level of an entire legion. The security operation on the line of supply would most likely fall to the forces under Fabius. Obviously, this reduces the numbers immediately available for any major offensive operations, unless the trains were pulled in from the escort duty.

Besides the forces in the field with the Dictator, the defensive and off load operations atthe port consume more manpower. Here the local population as well as allied forces from the surrounding region are exploitable. The forces required to defend the port can incorporate the manpower employed also to off load provisions. Again, a Carthaginian force would have to be of significant size to mount a credible threat to a fortified position the port would be upgraded to, at least the level of the Roman field fortifications. As with a Carthaginian threat to the supply line, the Romans could be capable of switching supply lines from one locale to another if the Carthaginians choose the make a major effort at such an adequately defended port. The sustainment operation at the port would require sufficietit personnel to off load, on the average~ those 46 short tons of food a day. However, unlike modem movement which avoids the vagaries and dependencies of seasons, wind and tide, the shipping of the period was not as systematic or reliable. A convoy carrying supply in great bulk would arrive and have to be cleared as quickly as possible. This is to be done through pure manpower without the assistant of modern equipinerit. This means that there would be periods of off loading which probably appeared like the scurry of a mass of ants at the mouth of a colony.

Given that far more than 46 tons would be unloaded in a day, the numbers to off load and warehouse the supplies imply a manpower pool which would on its own or with minimal supplementation be able to bold its own against a threat. On a rough estimation of a single individual carrying 40 pounds from the ship to a depot or warehouse within a half mile walking distance twice an hour, the daily food requirement of 92,400 pounds could be unloaded by 96 individuals in 12 hours. The equivalent of three maniples, 480 legionaries or allied soldiers, could supply 5 such teams thus unloading 5 days of the army's food supply in 1 day of work. This means that Fabius and the Romans did not have a problem in this instance with manpower, but does satisfy the position that such manpowerexisted to be utilized. The convoy is another matter.

Shortly after taking office and well before firiding himself before Hannibal in Apulia, the dependency of the convoys and their security presented Fabius with a challenge. The passage from Livy XXII, 11, previously cited is important for reexamination. Not only is the movement of bulk supplies by sea movement verified but also the threat to that supply line is viewed as such a critical issue that freedmen are quickly mustered to man craft to escort the shipping and provide coastal defense for the peninsula.

Like German wolfpacks in WWII, the Carthaginians can pick the time and location of such assaults. Without reconnaissance and surveillance capability, the Romans are forced to protect each convoy. While a dedicated force for coastal defense will provide some tactical protection for the forces being supplied in Italy, separate escort forces would have to accompany the naval supply routes to the legions Spain, Sardinia, and Sicily. Since the time of shipping can not be coordinated as in the modem sense, liberated from natures limitations, redundancies in both the merchant lift and warship escorts must be continuously operational. Even at the level of the merchant shipping there has to be some duplication. Forces which are resupplied as those in Cisalpirie Gaul which Lake Trasimene, looking from the probable ambush area, derive their material via the Po must employ smaller shallow draft ships. The legions, like those under the dictator in Apulia, that have a port can employ deeper draft vessels which handle greaterbulk. Given the strategy chosen to be exploited, the duplication of all these elements is necessary. Once again, the Roman manpower requirements escalate.

Of greater hindrance are the natural elements. The winds and weather are unpredictable. Consequently, the Romans must rely upon a 'push' supply system. Rather than the armies reporting their near term requirements and needs, a 'pull' system, those supporting the deployed legions keep sending materials whether requested or not. By overwhelming the depot and storage areas in the immediate area with supplies, the army in the field is not out of supply. The elaborate American 'pull' supply system employed in peacetime to minimize the logistical tail did not stand up to the requirements of multiple corps deployments during the conflict in the Persian Gulf. Consequently, the logistical command initiated this same system of 'push'. Vast amounts of materials were moved and positioned in the theater of operations just in case the need or requirement would arise. Two thousand years pass and logistics still are fundamentally similar.

Americans were not dependent upon nature, but the concept of 'having insurance' against the unknown would be in the minds of managers whether they think in Latin or English. Reflecting the minds and lessons learned by Rome is the record of M. Atilius Regulus consul in the First Punic War. Along with consul L.Manlius Vulso, M.A. Regulus lead Roman legions to North Africa in 256 BCE. They deployed to the region of Aspis which was not suitable to sustain the entire expeditionary force through the winter. Subsequently, the accompanying fleet and marked portion of the manpower were ordered by the Senate to return to Rome. The fleet was to return in spring with additional men and provisions.[CAH,VIII,pg 682]. Through a series of actions by both the consul and the Carthaginians, the Romans would be defeated. If the personnel accredited to M.A. Regulus are to be taken literally, then his force would be approximate to that of Fabius in Apulia. In the forty intervening years, it appears that with the legions deployed throughout the Eastern Mediterranean, the Romans had implemented a far more efficient system of sustainment. However, there are limitations and constraints such as overall lift capabilities in supporting too many deployments and too many stomachs with a finite number of ships both to carry material and to escort. This is not too dissimilar to the challenge of the allies in WWII in having limited lift capability to sustain simultaneous operations in the Pacific and Europe. There are managerial tradeoffs and some operations go wanting or are delayed awaiting the build up of sufficient material through the supply pipeline.

That logistical demand increases in the following year, 216 BCE. With the end of Fabius' dictatorship and the election of two new consuls, Gains Terentius Varro and Lucius Aemilius Paullus, the army in Apulia is reinforced. The exact number of men sent is subject to debate with Polybios, III, 107 reporting 8 legions were in the field before Hannibal. Additionally, the inference is that each is with an allied formation of equal size, bringing the total roll call to 72,000. As addressed in the initial installment of this analysis, the ceiling on the Carthaginian forces was most likely to be 25,000. An army of 72,000, even if doubled in depth, would have easily encircled the enemy with overlaps of 11,000 to each flank. Livy, XXII, 3 6, stipulates 10,000 fresh troops were raised as reinforcements. Whether these makeup for losses already sustained or this constitutes the annual levy of two legions [9,000] is not verifiable. However, if Rome suffered losses, the record also show losses on the part of the Carthaginians.

There would be some correlation in the remaining core numbers for both armies. Livy's numbers seem more probable given the size limitation for the Carthaginians, the vast call up for two previous consecutive years, and as it mimics a routine annual levy. This would bring the Roman force size to 6 total legions. These would trail Hannibal to Cannae. It also increases logistical demands by fifty percent. The reader can extrapolate the increased demands in the logistical tail. A remaining question would be where the Romans would encamp relative to the Carthaginians.

As addressed before, the Romans would primarily rely upon port base line of supply. In this geographical situation either the port of Sipontum [Lido de Siponto] northwest of Apri [Foggia] or any other the port south of the River Aufidus [Ofanto] , Barduli [Barletta], Turenum [Trani] or Natiolurn [Molfetta], would act as the base for the line of supply. In Note 3 Cannae of the CAH, Vol VIII, pg 7 10, the editors critique the issue as Kromayer stipulates that the traditional assumption of eight legions could only be supplied by the sea. Since the editors, as well as this analysis, view the record with the Romans having a markedly smaller force, they believe that much of this argument vanishes. I do not. Much like the instance with the length of an army in column, there is more to consider here. If the Romans establish their camp north, west or south to that of the Carthaginians, their line of supply, away from the sea would be northwest towards Apri and then to Sipontum or directly north towards Sipontum. The distance for the supplies is approximately 4 miles shorter than the supply line from Gerunium to Buca. As previously demonstrated in that analysis, this effectively removes an entire legion from the force for immediate battle. The coastal supply source would provide the shortest route, liberating the most manpower for military combat. This is not to say that this is the only correct answer. It is to reiterate that the view of the situation can be different in the consideration of logistical imperatives.

More History of Logistics: Part One

History of Logistics: Part Two

-

Returning to the Scene of the Action

Sustaining an Army

Supply, Size, and Tactics

The Writing of History

Back to Strategikon Vol. 1 No. 3 Table of Contents

Back to Strategikon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by NMPI

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com