In the years 217 and 216 BCE Rome faced the formidable challenge of the combined allied armies of the Barcas, a Carthaginian clan. Hannibal Barca, in the Italian peninsula, had led fellow countrymen, Iberians, Celts, and mercenaries with the objective of diminishing the presence of the young Roman Republic and avenging the Carthaginian losses of the previous conflict, the First Punic War. That army was the subject of initial installment of this analysis, The Reporting ofHistory and Reality of Logistics: A Re-evaluation ofthe Cannae Campaign, StrategikonVol. One, Issue Two. Through the employment of modern and contemporarymetrics, the validityof the traditional numbers long accredited by the classical records to Hannibal's army in Italy was earnestly challenged. The size of the army precluded the accomplishment of a documented road march within a specified period of time. The ability of local resources to maintain the army in an extended tactical posture before several legions of Rome was not feasible. The reliability of the literal truth of the numbers has been impeached The lack of specifies on these aspects presents an analyst with the challenges whichfaces a detective. The investigator has no eye witness accounts, but second and third band hearsay evidence. While those witnesses may have bad access to oral traditions and accounts, the written records haven't survived for scrutiny. The detective is left with ascertaining evidence by reconstruction or by analogous inference based upon known facts, Concurrent in this detective exercise is the recognition that the perceptions of contemporary civilization, culture, and society are not necessarily those of the people we examine. The concept of 'bean counting' and the use of census, in the statistical vernacular, is something inherent with our perceptions, not those of others. To us, the number ten thousand is taken literally, to others it may be simply understood to imply a large aggregate. The analytical problem is the same for Livy, Polybios, and modern writers. Most lack the hands on experience of daily operations of large military formations. The focus of histories and their drama is the battle, the lines neatly deployed, the valor or cowardliness before the enemy, and the triumph or defeat. Touse a well worn phrase, amateurs talk battles, professionals talk logistics.

The battlefield in popular and even in academic literature is generally represented as a one dimensional line in the scrolls or books. The battlefield in professional writings is multi-dimensional in operation. Depth of an army is not the number of lines in a column of men. It is the support tail from the tip of a gladius to the point of origin for food, equipment, training, and resourcing. That logistical structure is particularly critical to an army which must rely upon a 'system' rather than a 'great man' to make things happen. In the period of the Second Punic war, from the initiation of hostilities to the consequences of the renownedbattle of Carmae, the military forces of the Roman Republic relied upon such an organizational structure.

The battlefield in popular and even in academic literature is generally represented as a one dimensional line in the scrolls or books. The battlefield in professional writings is multi-dimensional in operation. Depth of an army is not the number of lines in a column of men. It is the support tail from the tip of a gladius to the point of origin for food, equipment, training, and resourcing. That logistical structure is particularly critical to an army which must rely upon a 'system' rather than a 'great man' to make things happen. In the period of the Second Punic war, from the initiation of hostilities to the consequences of the renownedbattle of Carmae, the military forces of the Roman Republic relied upon such an organizational structure.

Returning to the Scene of the Action

As the original installment began with an examination of the antagonists following the annihilation of the Roman force under consul Caius Flaminius at Lake Trasimene in June 217 BCE, this analysis of the Roman armies arrayed against Hannibal starts there as well. The strength of a consular army was nominally two legions. The uncertainty in the record is whether omot a complimentary size force composed of confederated Latin communities accompanied each Roman legion. The volumes of materials which try to define the nature of the Roman legion during this period ultimately rely upon the works of Livy and Polybios.( The legion as defined in Book VI, 19-26, Polybios is considered the model for the army during the initial phase of the Second Punic War.

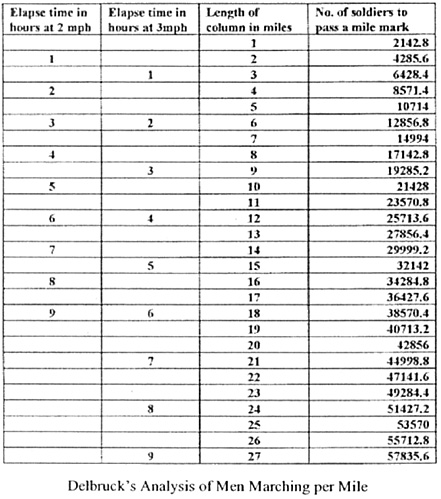

A singular legion would have a muster of 4,200 foot and 300 cavalry. This basic organization building block would then be combined with a second legion to 9,000 and with an equal number of allied formations combine to 18,000. The indirect measure of this assumption can be checked against the tactical situation presented at Lake Trasimene. When the record of a Carthaginian road march was calculated in the first installment, the length of the column, the time to travel a given distance, and the tactical parameters under which it had to be accomplished could not be reconciled with the ascribed size of the army. A similar situation occurs in this instance as well.

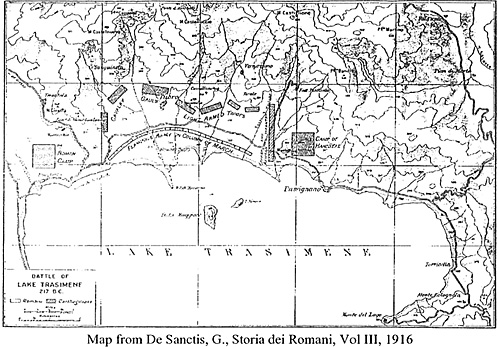

An examination of the topographical map of the battle site, from De Sanctis, G., Storia dei Romani, Vol III, 1916, [as reprinted in The Cambridge Ancient History, VIII, Rome and the Mediterranean] demonstrates that the distance from Flaminius' camp to the Cartbaginian road block before Passignano is just over 4 miles. The practicality of the narrative of the battle, like the night march, becomes subject to questioning given that the entire Roman force is annihilated. Nearly half the Roman force would still be in their fortified camp exiting, when the head of the column approaches the Carthaginian road block.

An examination of the topographical map of the battle site, from De Sanctis, G., Storia dei Romani, Vol III, 1916, [as reprinted in The Cambridge Ancient History, VIII, Rome and the Mediterranean] demonstrates that the distance from Flaminius' camp to the Cartbaginian road block before Passignano is just over 4 miles. The practicality of the narrative of the battle, like the night march, becomes subject to questioning given that the entire Roman force is annihilated. Nearly half the Roman force would still be in their fortified camp exiting, when the head of the column approaches the Carthaginian road block.

Jumbo Trasimene Map (slow: 174K)

The German J. Kromayer in Ancient Battlefields (Antike Schlachtfelder), III, 1, pp 148 is accredited with challenging the size accepted for the Roman forces in that it could not fit within the geographical confines. The Cambridge volume in the end book notes comments upon this issue. The writers of the Cambridge volume dismiss the point with "But no such calculation can be made vt4th precision." Interesting declaration in that military personnel do such calculations daily for the conduct of foot or motorized movements. The historian Hans Delbruck had already employed such practical inference as acknowledgedin the initial installment of this article. The probable length of the column is a practical measurable factor.

Given the known pieces of data, Flaminius would have under his command two legions, roughly 9,000 men. These exit their bivouac in road column. As the head of the column approaches the Carthaginian prepared positions it deploys. This provides just the sufficient room for the tail of the column to move forward and permit the backdoor to be closed by the Carthaginian elements laying in wait upon the Roman's left flank. Polybios makes good note that 15,000 perished on the lake shore, 6,000 would cut their way through the road block only to surrender the next day along with others for a total of 15,000 prisoners [Polybios, III, 84-5]. While these numbers can not be readily accepted based upon this analysis, the parole of the allied Italians legionaries should be recognized It implies that probably one of the two legions was in whole or part composed of Italian allies rather than Roman citizens.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Livius calls this army a Consular Army. By Roman Law it would number 18,000 at full strength, including two Legiones, and two Alae. The Law would have been extraordinarily important to command structures in that political power could be gauged by the number of troops and legios under command. However the army wasn't at full strength, Don's numbers work if 9000 are the total men caught in Hannibal's trap. Pictor probably claimed that the total loss of dead, andprisoners was 15,000. Polybios who has trouble reading Latin numbers (he makes this mistake with numbers over and over in his narrative see Walbank) forgets that Romans count inclusive. "at Pictor may have said was 15,000 casualties, 6000 prisoners. What he means is 15,000 with 6000 of those prisoners. No Roman or ally in that trap escaped, so the only prisoners were the ones who broke through the block at the advance. They might have broken through quickly as well. We don't have enough data to make a reasonable timeline. However it was a consular army. He was a Consul, he commanded four units, not two. If there was only two a Praetor would have been in command. SFP

The variable present within Flaminius' army is how it was constituted. By following the narratives of Livy and Polybios, it can be interpreted that this army was mainly composed of the legions which faced Hannibal at the River Trebia in 218 BCE. When the Romans cut their way through the Carthaginians at Trebia, they fell back upon the local colonies of Placentia and Cremona along the Po river in Northern Italy [Polybios, III, 74; Livy XXI, 56]. That force was composed of the legions raised in 218 BCE by the consuls Pubius Cornelius Scipio and Tiberius Sempronius Longus. The consular army of two legions under P.C.Scipio were destined for Spain and that of Longus for Sicily with an option for action in Affica. When the Celtic Boii became active against Roman interests and threatening the newly established colonies of Placentia and Cremona, the legions originally raised for P.C.Scipio were dispatched to Cisalpine Gaul and he was directed to raise new legions from the allies [Livy XXI, 17; Polybios III, 40]. P.C. Scipio proceeded with his new legions and assignment to Spain, debarking his force at Massilia [ modern Marseille] hoping to catch Hannibal crossing the Rhone. He misses this opportunity, sends the new legions with his family member Gnaeus Scipio in charge along to Spain, and returns to Italy to catch Hannibal debauching from the Alps in the Po valley. He takes command of the legions originally raised for his Iberian campaign. Meanwhile, T. S. Longus and his army is recalled from Lilybaeum [modern Marsala Sicily] to unite with the forces in the Po valley. These two consular armies assemble before the River Trebia and are subsequently defeated. ne elements of these two armies are withdrawn to both colonial cities by P.C.Scipio. He distributes the legionaries between both cities "to spare one town the heavy burden of two armies wintering in it." [Livy, XXI, 56]. The importance of the latter comment is its implication that a sizable portion of the combined armies survived the battle intact. This is complimented by Polybios, III, 75, which shows that significant supplies were required beyond that which the locale population could generate, while their own troops had abandoned their camp, retreated from the battlefield, had all now taken refuge in the neighboring cities, and were drawing their supplies from the sea and by the way of the Po." [Emphasis added].

Taking into the consideration the narrative description of G.Flaminius in both Livy and Polybios, it is unlikely that a man of his reputation and ego would take to the field anything less than what a consul was entitled, in this case, two full legions (9000 troops). The difference between that force and the sum of the force from the River Trebia would have remained on at the colonies to defend against the Boii and other Celtic tribes. By this measure and analysis, the consular armies sent into the field in the period before Cannae would be composed of two legions (9000) and not a combined force of two Roman and two allied legions (18,000). Upon this parameter, the logistical requirements of the Romans is to be examined.

After the disaster at Lake Trasimene, the Senate of Rome takes the extraordinary measure of appointing in June 217 BCE Quintus Maximus Fabius as dictator to face the Hannibal and the enemy before them in Italy. Upon taking office, Fabius raises new legions and unites these with the remnants of the legions under the prior consul Gnaeus Servilius whose cavalry element had been isolated and destroyed shortly after the disaster of Trasimene. It is a this point in the classical narratives that the size of the Roman force becomes confused.

After the disaster at Lake Trasimene, the Senate of Rome takes the extraordinary measure of appointing in June 217 BCE Quintus Maximus Fabius as dictator to face the Hannibal and the enemy before them in Italy. Upon taking office, Fabius raises new legions and unites these with the remnants of the legions under the prior consul Gnaeus Servilius whose cavalry element had been isolated and destroyed shortly after the disaster of Trasimene. It is a this point in the classical narratives that the size of the Roman force becomes confused.

Livy, XXII, 11, reports that "Fabius accordingly declared his intentions of adding two fresh legions to Servilius' army, they were raised by the master of the Horse and ordered by the dictator to report at Tiber on a given date." Polybios, III, 88, reports "Meanwhile Fabius, after offering sacrifices to the gods following his appointment, also took the field, with his second-in-command and the four legions which had been conscripted for the emergency. He joined forces near Narnia with the army which bad been on its way from Ariminum to reinforce Flaminius, and there be relieved Gnaeus Servillius, the present general, of his command on land..." From the previous examination it appears that in this case Livy is probably more reliable.

These new legions are not raised in isolation to what has been happening in the preceding two years. When the Senate finally accepted the prospect that war was inevitable with the fall of Saguntum in 218 BCE it mobilized a significant force. Besides forces already on active duty, the Senate enrolled four legions for the two consuls and then two additional legions to replace those originally raised for P.C.Scipio but diverted to Cisalpine Gaul. Prior to the investment of the office of dictator, the Senate also enrolled two legions, one to be sent to Sicily to continue the operations begun by Consul T.S.Longus when he was recalled north to the Po valley, and a second to be sent to Sardinia. Normally, two legions are raised per year. Here are 8 new legions. This is not as draining as recovering from the impending loss to be experienced at Cannae, but definitely an action of exceptional proportion. Within the context that the previous two defeats were attributable to questionable leadership and, in the case atLake Trasimene, to most likely being out numbered, it would seem that the step of appointing a leader with a reputation of a more methodical approach to campaigning would be the answer to Hannibal's tactical successes. Fabius seeks to exploit Roman operational strengths and Carthaginian weakness.

The facts were that the enemy's forces bad undergone a continuous trainingin war which bad begun in their earliest youth, they had a general who had been brought up with them and had been accustomed from childhood to operations in the field, they had won many battles in Spain, and had twice in succession defeated the Romans and their allies; and above all they had cast aside any alternative course of action, so that their only hope of survival rested in victory. On the Roman side the situation was exactly the reverse: his army's comparative lack of experience made it impossible for Fabius to face the enemy in a pitched battle, and so on consideration he decided to fall back upon those resources in which the Romans were superior. These were an inexhaustible supply of provisions and manpower, and to these advantages he clung, and devised his strategy accordingly. [Polybios, Book III, 89]

The Dictator marches towards the Carthaginians which are operating the Apulia region. Unable to induce Fabius to open battle, Hannibal launches a campaign of pillage and destruction through Samnimum to Campania. Carefully and deliberately Fabius shadows the enemy and nearly boxes them within the topographical confines of the Falemian Fields and Capua. Hannibal and his forces escape by exploiting confusion and the cover of night. He returns to Apulia for winter quarters in a less devastated district north of Luceria around the village of Gerunium. The Romans follow. They establish their encampmentnot too far from that of the Carthaginians.

It is at this point that the topic of logistical sustainment becomes a key factor in determining the probable size of the contending forces. The first iteration of this article examine the limitations of Carthaginians to supply their forces by foragingin this tactical situation. As stipulated by Polybios, the Romans would have an inexhaustible supply of food. "Since he could always count on the abundance of supplies to his rear, he never allowed his soldiers to forage or to become separated from the camp on any pretext." [Polybios, Book III, 90.]

This alludes to sustainment by logistical management methodologies similar to modern armies. A commissary office in name or function would establish a process of collecting and moving the material to the location of deployed forces. Some of the organization of that mechanism is identified in the narrative shortly after Fabius takes his office.

"Almost immediately afterwards letters arrived from Rome reporting the capture near the harbour of Cosa by a Carthaginian squadron of some merchant vessels carrying supplies from Ostia to the army in Spain. The consul was given orders to go to Ostia at once, to man with fighting troops and allied seamen all ships either there or up the river near Rome, and to use them for the pursuit of the enemy squadron and the defense of the Italian coast. In Rome a large force was enlisted; even freedmen, if they bad children and were of military age, had taken the oath. Of this force, raised in the capital, all under thirty- five years of age were sent to serve with the fleet; the remainder were left to guard the city." [Livy XXII, 11]

This passage is important for what is reveals. The movement of bulk supplies is being accomplished by sea movement. The threat to that supply line is viewed as such a critical issue that freedmen are quickly mustered to man craft to escort the shipping and provide coastal defense for the peninsula. When the surviving Roman forces from the River Trebia were wintered in Cremona and Placentia, their sustainment was by the sea and the River Po as earlier noted. This is the method upon which Fabius is to exploit his ability to keep his less skilled forces within the protection of the fortified camp. This is the source of his inexhaustible supply of food. It is also manpower intensive. When extrapolated for the Roman forces deployed not only in Italy but the entire Eastern Mediterranean, the leverage of that manpower will be something that the Carthaginians will not be able to equal.

Movement of bulk supplies by pack animal has limitations. The use of wagons is specifically limited in the Romans' case as they had failed to adopt or develop an efficient harness system to exploit wagon based carriage. That leaves the Romans as with the Carthaginians with pack animal portage. The pack animals themselves consume what they carry. Donald W. Engels, Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army, Annex I, addresses this problem. These animals can lift 200 lb. of materials. However, the animal also consumes 20 lb., 10 of grain and 10 of fodder. After 10 days, they would consume all that they carry. A supply route could not extend greater than 5 days march from its depot point as it must retrace its path on a return march for a total of 10 days. Technically, this 5 day march would deliver 20 lb. with the supply train receiving its 10th day march food at the depot upon its return. Obviously there is an inverse relationship between the supportable size of the army and its distance from its depot. Therefore it obligates planners to move the bulk supply depot as close to the army it is supporting as is possible. This is the challenge Fabius' staff must work in order to exploit this operational advantage over the Carthaginians as they winter in and around Gerunium.

With the bulk of the subsistence moved by sea, that makes a functional port facility or viable off load terrain critical. Near the neighborhood of Gerunium is the Roman era port of Buca (modern Termoli). From Buca, along the coast and then up the Fortore river line to Gerunium is approximately 55 kilometers or 35 miles. While the Romans could draw upon Luceria and Apri (modern Foggia) for a short period, they, unlike the Carthaginians, must still calculate feeding the local population. The former routing is away from the location of the enemy while the latter route lying astride the enemy army would be subject to greater compromise to raids and interdiction by the Carthaginians. Sustainment must be organized and maintained on a supply infrastructure for the immediate winter and spring, an extended period of time. Buca, as the source, provides the more secure route.

More History of Logistics: Part One

History of Logistics: Part Two

-

Returning to the Scene of the Action

Sustaining an Army

Supply, Size, and Tactics

The Writing of History

Back to Strategikon Vol. 1 No. 3 Table of Contents

Back to Strategikon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by NMPI

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com