Hougoumont in Retrospect

The intensity of the infantry fire around Hougoumont was enough that "the trees in advance of the chateau were cut to pieces by musketry." The exhausted defenders turned in for the night on the position they defended.

Clearly with two and a half divisions committed, Hougoumont absorbed almost the whole of Reille's corps; perhaps 13,000 infantry and 50 guns, including Kellerman's artillery, tied up for all or most of the day. It was a poor use of troops. It is possible, but unlikely, that Napoleon thought the 2nd Corps was too battered by the fighting at Quatre Bras to be of much use at Waterloo, and therefore was not concerned with it being drawn into the assaults on Hougoumont. If so, the French losses at Quatre Bras may have been more severe than most accounts describe.

It is difficult to estimate French casualties at Hougoumont, as the entire 2nd Corps, Bachelu's division particularly, had been so heavily engaged at Quatre Bras two days before. Post-battle returns exaggerate combat losses due to the scattering of troops during the retreat, so an estimate of 5,000, as given by Julian Paget and Derek Saunders in Hougoumont, seems reasonable.

Why had the French generals

become so obsessed

with Hougoumont?

An alternative method of estimating French losses can be reached by tabulating French officer casualties at Waterloo. Using Scott Bowden's invaluable book Armies at Waterloo, it appears that the divisions of Jerome, Foy and Bachelu had 28 officers killed at Waterloo, and 166 wounded or missing. Assuming twenty rank and file lost for each officer, this extrapolates to total casualties of just over four thousand.

The severity of the fighting is illustrated by the fact all three French division commanders were wounded at Hougoumont. Jerome was wounded, Bachelu was seriously wounded by a shell splinter, and Foy was hit and carried from the field, though he was back in command late in the day.

Obsession

Why had the French generals become so obsessed with Hougoumont? Perhaps it was because the position would have made a superb point from which to attack the heart of Wellington's main line if it had fallen. The loss of La Haye Sainte marked the nadir of Wellington's day: the loss of Hougoumont would have been fatal. Perhaps Wellington's gradual reinforcement of the garrison made it seem vulnerable for most of the day. The risks Wellington took may have had the benefit of luring the French to overcommit, but it was a gamble he might have lost but for Macdonell's heroics.

On the other hand, Wellington's strategy may have mattered less than the lack of a coherent French plan at Hougoumont. Reille's three division commanders each moved off to fight their own private battles, uncoordinated and undirected by Reille. Reconnaissance and preparations to assault a walled chateau were nonexistent.

Adding to the controversy, Julian Paget and Derek Saunders have a very interesting footnote in their new book about a reminiscence of Jerome several years later. According to them, Jerome said that about an hour after the battle began, Napoleon told him, "If Grouchy does not come up or if you do not carry Hougoumont, the battle is decidedly lost -- so go -- go and carry Hougoumont -- coute que coute." Unfortunately, the authors do not mention their source, but if Jerome is to be believed, Napoleon's encouragement to his headstrong but untalented brother was dangerous if not foolish.

Wellington was lucky

and Hougoumont was a

battle that suited him.

The success of Wellington's strategy is often exaggerated by an underestimate of the forces he committed there. In all there were the two battalions of Coldstream and Scots Guards, the two light companies of the 1st Guards, several companies of Hanoverian light troops and perhaps three battalions of landwehr, a battalion of the KGL and perhaps more of their light companies, and a battalion each of Nassauers and Brunswickers. This comes to 6,600 men committed, about half the French total engaged at Hougoumont. Of course, the allied troops were not all there at the same time, but this is where their major efforts were made.

Of this 6,600, about 1,200 appear to have become casualties. This is a much higher number than is sometimes quoted, but it is still clear that Wellington got a better return on his investment in this attritional struggle.

Some authors have tried to impose a rigid structure of phases to the Hougoumont action. It is true that there were major French surges as new formations were committed, which usually led to new waves of allied reinforcements in response. Emphasizing these as separate, specific phases gives a neat view in retrospect. But if the real thing had been so tidy, some very competent French generals would not have dashed so many good troops against such impossible obstacles.

Instead, broken up by the woods, the hedges, and very effective artillery fire, French brigades stumbled into unseen or unexplored defenses. As officer after officer went down, brigade assaults disintegrated into repeated piecemeal attacks by battalions, companies, and finally handfuls of men following some trusted officer or sergeant, until the arrival of a new wave of fresh troops.

Instead, broken up by the woods, the hedges, and very effective artillery fire, French brigades stumbled into unseen or unexplored defenses. As officer after officer went down, brigade assaults disintegrated into repeated piecemeal attacks by battalions, companies, and finally handfuls of men following some trusted officer or sergeant, until the arrival of a new wave of fresh troops.

Ironically, it may have been due to this very confusion that apparently futile French attacks came close to success a few times, especially when the gate was left open, or when the garrison was running out of ammunition. But Wellington was lucky, and Hougoumont was a battle that suited him. Whereas the French command system collapsed, the Duke was at his best, economically deploying his forces bit by bit, by battalions or even companies, to the best advantage.

Notes on the Orders of Battle

There is a surprising amount of confusion as to what troops fought at Hougoumont. Some of it stems from the difficulty of drawing a distinct boundary to the Hougoumont fighting. Allied troops that were behind the sunken lane or in action in the fields just to the east can be included or excluded from various reckonings just because of this vagueness.

Still, if there was as much confusion over where large bodies of troops fought in any of the major battles of the American Civil War, it would be considered a scandal, and scholars would be rushing to fill the void. Memoirs and unit histories of French and German participants should be able to clear up some of the gaps in our knowledge.

As to the French, it is fairly certain that all of Jerome's division assaulted Hougoumont. There is some debate as to how much of Bachelu's division was committed. Some sources have a significant number fighting under Ney near La Haye Sainte. Bachelu's division had suffered the most at Quatre Bras, and probably was only about half strength at Waterloo. Most of the division may have been diverted to Hougoumont, where Bachelu was wounded in the vicinity. If it didn't fight here, it would be interesting to know where Bachelu's division suffered such high casualties. Some sources say only one brigade of Foy's division fought here, but as with Bachelu's men, if they weren't at Hougoumont, they made strangely little mark elsewhere, while Foy himself was present.

Some Brunswickers,

probably the Avant-Garde,

may have helped clear the wood

at the end of the day.

In the allied line-up, the presence of the Guards is well documented. The exact number of Hanoverian riflemen is sometimes disputed; the mass of British accounts presume one company, but two may have been present. Sometimes Hanoverians from the Grubenhagen Battalion are said to be present alongside those from the Luneberg Battalion.

On the Nassauers, there is more disagreement. One British observer, Sinclair, wrote of "about 300 of the Nassau troops, some of whom, however, did not stay long, owing, it is said, to their not having been sufficiently supplied with ammunition". This and other accounts may have been swayed by national bias. Most sources are certain the entire battalion was deployed. Andrew Uffindell quotes the Nassauer's after-action report that they actually had a company in the chateau's buildings, which is never mentioned by any of the Guards's accounts, and if true would be cause to reconsider the latter's sources.

The presence of the 2nd Line Battalion, KGL, seems definite, but some sources mention the arrival of the rest of its brigade. Yet du Plat clearly retained a substantial force on the ridge above, so it is doubtful that more than the light companies descended to Hougoumont. There is similar debate as to the deployment of Halkett's 3rd Hanoverian Brigade. While some authors mention the entire brigade, as noted before his own account makes it clear that he kept the Osnabruck Landwehr Battalion with him. The Quackenbruck Battalion may have remained in reserve above Hougoumont; it suffered so few casualties they may have been the result of only artillery fire.

Some Brunswickers, probably the Avant-Garde, may have helped clear the wood at the end of the day, but there are few mentions of their presence, and it's doubtful that additional battalions had more than a cursory role.

Some of the confusion over the participation of the German contingents comes from how they were deployed. Many of them were in reserve behind the sunken road, critical in holding the ridge above and to the east. Assuming this to be their primary role, the German participation at Hougoumont has been downgraded. Peter Hofschroer's upcoming book on Waterloo using German sources may finally clarify these questions.

Allied Losses at Hougoumont

| Formation | Strength | Killed/Wounded |

|---|---|---|

| Light Coys., 1st Guards | 165 | 100* |

| 2nd (Coldstream) Guards | 1,100 | 56/263 |

| 3rd (Scots) Guards | 1,160 | 45/214 |

| 1st Battalion/2nd Nassau | 700* | 150* |

| Hanoverian Jager | 160* | 35* |

| Luneburg detachment | 100* | ? |

| 2nd Line Battalion, KGL | 550 | 20/93 |

| KGL Light Companies | 150* | ? |

| Brunswick Avant-Garde | 635 | 7/20 |

| Bremervarde LW Bn | 655 | 18/28 |

| Quackenbruck LW Bn | 609 | 2/35 |

| Salgitter LW Bn | 644 | 20/89 |

*These numbers are estimates; for casualties they are pro-rata estimates from the casualty totals of parent formations. Question marks represent unknowns, but these casualties are presumed to be negligible.

Some of these casualties, sometimes a significant proportion, may have been suffered from French artillery fire as the battalions waited on the ridge above. If more Brunswick or KGL battalions were present, it would raise the number of troops committed by a thousand or so, but not alter the casualty numbers significantly as their participation was limited.

The two light companies of the 1st Guards suffered nearly 61% casualties. The Coldstreams lost 29% while the Scots Battalion suffered 22% losses. The Nassauers, Hanoverian Jagers and KGL Battalion lost about the same percentage as the Scots: 21% each. French percentage of losses is estimated around 35% for the divisions involved in the attacks. Overall the French lost three to four times as many men in the fighting at Hougoumont.

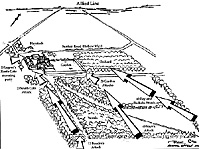

Large version of Schuldt drawing ( © Rick Schuldt) (slow download: 89K)

Large version of Schuldt drawing ( © Rick Schuldt) (slow download: 89K)

Jumbo version of Schuldt drawing ( © Rick Schuldt) (very slow download: 198K)

Recommended Reading

Siborne's History and Letters were relied upon extensively for this article (both republished by Greenhill Books and available from Stackpole in the U.S.). Despite some criticism, Siborne's History is still the best account of the battle in English, and the Letters a great first-hand source. There is no French equivalent. We look forward to Greenhill's publication of the remainder of Siborne's Letters.

The primary published French source, Charras's Campagne de 1815, has no translation or recent edition, and will be difficult to find, as is Scott Bowden's excellent Armies at Waterloo, also currently out of print.

Three recent British publications are important, above all Hougoumont by Julian Paget and Derek Saunders, published by Leo Cooper and available from Combined Books in the U.S. Also recommended is Gentleman's Sons, a history of the British Guards, by Ian Fletcher and Ron Poulter. On the Fields of Glory, a recent book by Andrew Uffindell, is a pleasant surprise, and well worth reading. Another quite useful reference is Tony Linck's Napoleon's Generals: The Waterloo Campaign.

About the author:

John Brewster works in the publishing department of the Emperor's press and has been on the staff of the magazine since its inception.

Hougoumont

-

Introduction

First and Second French Assaults

More French Assaults

In Retrospect (analysis)

Hougoumont Today

French Line Grenadier (profile)

British Foot Guards (profile)

Excerpt from Lt. Ellison, 1st Foot Guards

Order of Battle

Diorama

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #7

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by Emperor's Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com