"The success of the battle of Waterloo depended on the closing of the gate of Hougoumont." -- Duke of Wellington

"The success of the battle of Waterloo depended on the closing of the gate of Hougoumont." -- Duke of Wellington

Waterloo is one of the most famous battles in history, probably the most well known battle of the Napoleonic Wars. Within the battle, the struggle for control of the walled farm of Hougoumont is perhaps as significant to the British as the defense of the Little Round Top at Gettysburg during the Civil War is to Americans.

Despite its fame, there are still many unanswered questions and even some mystery surrounding what happened at the Hougoumont chateau on 18 June, 1815. The staff of Napoleon magazine attempts to answer some of these questions, reveal some myths, and offer a useful and colorful graphic presentation.

Large version of Rocco painting, "Great Gate at Hougoumont" (very slow download: 213K)

While only a part of the larger battle of Waterloo, the fighting around the chateau of Hougoumont has become almost as famous as the battle itself. The Duke of Wellington thought he came close to losing Waterloo there [note the Duke's famous quote at the top]. Most historians believe that the wasteful French assaults against the chateau are a major reason Napoleon lost. In any event, puzzling aspects to the Hougoumont fighting remain, and, despite all that has been written about Waterloo, considerable questions remain.

The fighting at Hougoumont should have been a diversion, part of the French efforts to wear down the Anglo-Allied army. Napoleon was trying to distract Wellington from the true object of his attacks, the Anglo-Allied center. He hoped to drain Wellington's reserves by attacking Hougoumont, but he did not anticipate any key result there.

At Waterloo,

Wellington had little choice

but to occupy Hougoumont.

Napoleon often tried to use a small portion of his forces to neutralize a considerable proportion of the enemy's; however, on this occasion, Wellington may indeed have turned the tables on him. Yet even this is not incontrovertible. In holding this objective Wellington had to commit far more of his strength than is generally recognized.

The use of the walled farms of Hougoumont and La Haye Sainte as outworks to the main allied position on the ridge behind is often quoted as typical of Wellington's tactics. It is similar to his use of the village of Fuentes d'Onoro (3-5 May, 1811) to anchor his line in the battle of that name, where again he skillfully fed in reinforcements to wear down French assaults.

The use of the walled farms of Hougoumont and La Haye Sainte as outworks to the main allied position on the ridge behind is often quoted as typical of Wellington's tactics. It is similar to his use of the village of Fuentes d'Onoro (3-5 May, 1811) to anchor his line in the battle of that name, where again he skillfully fed in reinforcements to wear down French assaults.

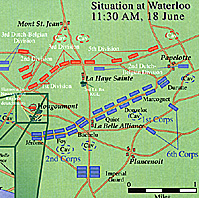

Large Version of Map (very slow download: 168K)

But Wellington was not the only general who knew how to use strongpoints to anchor his line: Aspern-Essling (21-22 May, 1809) has already been described in Napoleon #3. Marshal Davout's use of the village of Hassenhausen at Auerstadt (14 October, 1806) and Marshal Marmont's use of Mockern in 1813 at Leipzig are also masterful examples of this tactic.

Hougoumont Must Be Defended

At Waterloo, Wellington had little choice but to occupy Hougoumont. Not only did it prevent the deployment of the French massed batteries there against the allied troops behind it, but it also blocked a dangerous covered way into the heart of his position, for the ridge line on which Wellington made his stand comes to an end behind Hougoumont. In fact, Wellington came close to losing the battle by undergarrisoning Hougoumont; such a mistake helped cost him La Haye Sainte. Properly known as the Chateau de Goumont, the map most of the generals were using (Ferrari's) showed it as Hougoumont.

The main house, or chateau, of Hougoumont was a substantial brick building. North and south of it were courtyards formed by similarly sturdy brick buildings. The northern courtyard was surrounded by farm buildings, and a large gate in the westernmost side of its north wall provided the main entrance to the complex. This gate was closed by two large wooden doors, held in place by a heavy wooden bar, but it was kept open initially to allow communication to friendly forces on the ridge to the north.

The main house, or chateau, of Hougoumont was a substantial brick building. North and south of it were courtyards formed by similarly sturdy brick buildings. The northern courtyard was surrounded by farm buildings, and a large gate in the westernmost side of its north wall provided the main entrance to the complex. This gate was closed by two large wooden doors, held in place by a heavy wooden bar, but it was kept open initially to allow communication to friendly forces on the ridge to the north.

The southern courtyard, closest to the French, was surrounded by the gardener's house, some stables, and some offices. It had a gate on the southern side which was so firmly secured it was never in danger of being forced during the battle. In the east side of the southern courtyard was another gate, which led into a large garden. This was laid out in a very formal style and, more importantly, was enclosed to the south and east by a high brick wall. The wall's defensive benefits were improved with loopholes and firing steps to make them very strong positions.

East of the garden was a larger area, devoted to an orchard. It was lined with a high, thick hedge. The hedge on the north side continued to serve as the northern boundary of the garden as well, and hid a sunken road which followed the northern side of the Hougoumont complex until it reached the northern gate. This sunken road was an invaluable reserve position and rallying place for the defenders.

While generally recognized

as excellent infantry,

British Guardsmen were never regarded

by the rest of the army

with the same respect enjoyed

by their French counterparts.

A narrow lane ran along the south side of the buildings, garden and orchard. Its hedge, a prolongation of the orchard hedge, with a row of apple trees, served to disguise the formidable nature of the garden walls from the French coming from the south.

South of this lane, opposite the buildings and garden, a wooded area extended for about 350 yards, and was a little less than three hundred yards wide. To its east, and south of the great orchard, were two enclosed fields, fenced with more hedges, and ditches on the inner sides.

From the ridge to the north, a road lined with fine tall elms ran down past the western side of the buildings, connecting with the sunken road and the north gate, and splitting as it went south. One spur was the lane which passed along the south side of the garden and orchard. Another spur went due south into the French position. A path led southeast across the wood and fields towards the village of La Belle Alliance.

British Garrison

The position was garrisoned by the light companies of the British Guards battalions (4 companies), the 1st Battalion of the 2nd Nassau Regiment, and 100 Hanoverians from Battalion Luneburg and a company of jager of Kielmansegge's Hanoverian brigade. The Hanoverian jager were armed with rifles. Rifles could be loaded and fired as quickly as the smoothbore muskets most infantrymen were equipped with. However, rifles could also reach a greater range with much better accuracy than muskets if special rifle ammunition requiring a longer time to reload were used, as the attacking French learned to their regret.

The position was garrisoned by the light companies of the British Guards battalions (4 companies), the 1st Battalion of the 2nd Nassau Regiment, and 100 Hanoverians from Battalion Luneburg and a company of jager of Kielmansegge's Hanoverian brigade. The Hanoverian jager were armed with rifles. Rifles could be loaded and fired as quickly as the smoothbore muskets most infantrymen were equipped with. However, rifles could also reach a greater range with much better accuracy than muskets if special rifle ammunition requiring a longer time to reload were used, as the attacking French learned to their regret.

The light company of the 2nd (Coldstream) Guards were in the buildings, while the light company of the 3rd (Scots) Guards was in the garden, except for a section which took position by a haystack just to the southwest of the buildings. These were under command of Colonel James Macdonell.

The light companies of the two battalions of the 1st Guards took position on the ridge above the orchard under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Lord Saltoun. The 1st Guards would earn their name of Grenadier Guards later that afternoon.

While generally recognized as excellent infantry, British Guardsmen were never regarded by the rest of the army with the same respect enjoyed by their French counterparts. Any reverse the Guards suffered was seen by the rest of the army not with dismay, but rather a certain jealous satisfaction. However, Wellington did not risk any morale problems by placing them in an exposed position.

The Hanoverian jager had a uniform and a rifle very similar to a British rifleman's. The Luneburg Battalion was also considered a light battalion and dressed in British rifle green. As the Nassauers were also uniformed in green, the woods around Hougoumont were filled with green-clad German light infantry, while behind them the buildings, garden and orchard were held by Guards light infantry dressed in red. The Guards, Nassauers and probably the Hanoverians had been engaged at Quatre Bras on the 16th (two days before Waterloo), but the Guards light companies had not suffered as much as their parent battalions.

Oddly enough, the Nassau detachment was from the 2nd Nassau Regiment, whose brigade was on the extreme east flank by the village of Papelotte, rather than from Kruse's 1st Nassau Regiment, which was on the center of the ridge not far off. (At right, Naussauer skirmishers in the woods south of Hougoumont. From Knotel)

Oddly enough, the Nassau detachment was from the 2nd Nassau Regiment, whose brigade was on the extreme east flank by the village of Papelotte, rather than from Kruse's 1st Nassau Regiment, which was on the center of the ridge not far off. (At right, Naussauer skirmishers in the woods south of Hougoumont. From Knotel)

This meant that most of the defenders, both the Nassauers and Guards, had fought at Quatre Bras against the same French of General Reille's 2nd Corps now facing them across the valley.

Opposite the Hougoumont complex stood General Foy's division, but General (and Napoleon's youngest brother) Jerome Bonaparte's division just off to the west began the assault. Jerome's left flank was covered by General Pire's cavalry division, while General Bachelu's division stood between Foy and the French center.

All four divisions belonged to Reille's corps, and most of them became entangled in the Hougoumont "battle within a battle". Reille's corps had seen hard service at Quatre Bras two days earlier, but seemed confident as the day began. With Napoleon and the rest of the army present, they expected a happier outcome.

Hougoumont

-

Introduction

First and Second French Assaults

More French Assaults

In Retrospect (analysis)

Hougoumont Today

French Line Grenadier (profile)

British Foot Guards (profile)

Excerpt from Lt. Ellison, 1st Foot Guards

Order of Battle

Diorama

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #7

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1996 by Emperor's Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com