Vietmeyer Hill

Vietmeyer Hill

This feature played a big role in much of my early miniatures wargaming. Located in one of Jack Scruby's Table Top Talk tactical problems, the hill bore the name of a wargamer. Of that I was sure, but, since this was my only issue of the magazine for the next 30 years, that's all I knew for a long time. (Didn't stop me from fighting for it!).

It turned out that Fred H. Vietmeyer was a regular contributor to Scruby's publications, especially in the arena of Napoleonic wargaming. His series on the organization of the main armies of the period was even re-published as a separate item by Scruby. So it was no surprise when I found out that he was author of one of the early rule sets specializing in the Napoleonic period.

Column, Line and Square was a collaborative project that came together over the course of the 1960s. Developed by Vietmeyer and the Midwestern Napoleonic Wargamer Confederation, the rules were a big departure from the simpler approach of Scruby's Fire and Charge. In fact, as I recall, the latter half of the 60s saw the beginning of a never ending discussion of playability versus realism in boardgaming, and here we have evidence that miniatures gaming was seeing the same phenomenon. John C. Candler's Warfare du temps de Napoleon added further weight to the realism side of the balance with its mid-60s release. These two titles were significant steps away from the more generic rules we've seen, and went several steps farther than Fire and Charge in their attempts to recreate the "feel" of early 19th century warfare.

Both titles begin with simultaneous movement as the basis for activity. Unlike Scruby, who simplified matters by having players move together, but from opposite ends of the table, these two authors depended on map drawing for setting out the movement of the units on the table. This immediately introduces some complexity in execution as provision has to be made for those occasions where the opponents' orders are mutually exclusive, and both rule sets answer the appropriate questions adequately. Candler also suggests the use of a curtain down the center of the table as an alternative for the initial set up and/or the use of cards to represent groups of troops until they can be "seen" by the opponent's troops. Both ideas we've seen before. A final factor emphasized by both authors is the speed at which orders must be drawn on the maps. Both recommend 10 minutes for this activity, an adequate timeframe, but quick enough to force a sense of immediacy on the players.

Vietmeyer introduces weather as an important part of the rules. Providing historical examples where different types of weather played a role, he introduces a 1/3 chance of some imperfect weather conditions. These range from windless days, where gun smoke doesn't move and remains to obstruct vision, through rainy days which impedes fire to soft ground, which can also appear after a rain, which impedes movement. Terrain is also very explicitly defined in Vietmeyer's rules, with several varieties of woods, swamps and hills producing varying effects on the activities of the troops passing through them. While not ignored in Candler, terrain is less specifically dealt with.

Vietmeyer introduces weather as an important part of the rules. Providing historical examples where different types of weather played a role, he introduces a 1/3 chance of some imperfect weather conditions. These range from windless days, where gun smoke doesn't move and remains to obstruct vision, through rainy days which impedes fire to soft ground, which can also appear after a rain, which impedes movement. Terrain is also very explicitly defined in Vietmeyer's rules, with several varieties of woods, swamps and hills producing varying effects on the activities of the troops passing through them. While not ignored in Candler, terrain is less specifically dealt with.

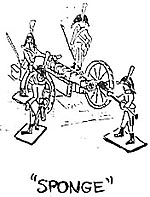

The rules differ a bit in scale, with Vietmeyer's models representing 20 soldiers and Candler's only one. This doesn't appear to affect the major elements of the games too much in practice, as both scales allow the authors to concentrate on the "Field Regulations" both use to define the basic formations permitted the various troops types. These follow the standard formats, with column, line and square being the dominant infantry arrangements. Vietmeyer spends more time discussing and preparing rules within these parameters, while Candler, taking advantage of his more "personal" scale, introduces rules on the individual level, with stragglers and their disposition appearing early in the movement rule complex. In both sets, players may choose to do two of three basic operations, thus one can move and face, or move and fire, or face and fire, but not all three.

Other than artillery fire, combat takes place after movement in both rules, with some exceptions. Fire is also simultaneous. With "crossing fire" and "fire and charge" movements, it can get a bit complex. Both authors give enough examples and regulation to make clear what the process involves, though. Because of the concentration on this period, the authors are also able to refine their fire tables to take into account the variety of weapons available, especially in artillery. We don't just differentiate between shot and cannister, but have many different weights of cannon ball to work with. Volley fire is a simple equation in both sets of rules and skirmisher fire is not much more complex. Melee is likewise straightforward and similar to fire in execution. Candler pays a bit more attention here with his concentration on the individual soldier.

One interesting idea in Candler, which we haven't seen before, is the use of colored dice to represent different casualty classes in combat. A red die is used for kills and a green one for wounds. Additionally, a white die may be chosen if prisoners are desired. The provided for kills and some have made provision for prisoners, but this is the first where wounded troops play an important part on the tabletop. Of course, if you have wounded, you also need a surgeon and will probably have some method of aiding the troops to get back into the fray, and Candler takes care of this neatly.

Morale affects these games significantly, with mandatory tests coming up when under fire, when charged and when negative results are suffered by nearby units. In both sets, the death of the commander is an important feature to be avoided. In Vietmeyer, it leads to morale tests by all units. In Candler, as he once more emphasizes the individual actor, to the immediate loss of the game!

Both sets of rules have supply factors built into them, especially for artillery. This leads to a bit of record keeping, or markers of some sort, to keep track of the supply situation. Supply wagons become an important factor in both games and targets for wandering light cavalry.

Both sets of rules have supply factors built into them, especially for artillery. This leads to a bit of record keeping, or markers of some sort, to keep track of the supply situation. Supply wagons become an important factor in both games and targets for wandering light cavalry.

Napoleonic era army organization is quite interesting, with each state's arrangement varying to some degree or another from every other. Vietmeyer's rules reprint much of the work he did for Table Top Talk and Candler also takes the time to describe army arrangements for the major players. While not affecting the basic rules, this adds considerably to the flavor of the period, and draws the gamer into the historical background of the game much more completely than a simpler set might do.

Vietmeyer's rules end here with a short bibliography, but Candler spends as much time with appendices as with the main rules. He includes a simple set of rules for sea warfare, using a scale consistent with the land wargame. He also includes rules for "International Wars," which is really a campaign design set, complete with umpires and room for espionage and politics. Following these supplementary rules, he adds a collection of short biographies of the major players, a brief history of the period and a short discussion of tactics used on Napoleonic battlefields. There's a bit of "How-To" regarding painting figures and such, the obligatory list of suppliers and then, surprisingly, a list of gamers and their addresses! This was a fascinating part of the book to me, as I recognized many of the names of contributors to Scruby's publications, players important for other reasons in wargaming history, and a few who are still active gamers. I wonder how many of those still have the same address?

These two rulesets represent an important point in the history of our hobby, when gamers began to move towards much more specific periods of interest. No more Ancient/Medieval, Horse and Musket and Modern. From this point forward, we'd find rules devoted to almost any period, sometimes just single battles, that interested us. While some of the simplicity of the previous rule makers was lost, we gained a tremendous amount of re-creation, allowing us a much better taste of what it may have been like on our battlefield of choice. It's been fascinating to see how we've tried to balance that flavor with simplicity over the decades which followed, and gratifying to see how we're still succeeding in creating so many excellent variations on this theme of Napoleonic wargaming.

Sources

Candler, John C. Miniature Wargames du temps de Napoleon. 1964.

Vietmeyer, Fred H., et al. Column, Line and Square. 2nd ed. Champaign, IL: Wilson's Limited, 1968.

Vietmeyer, Fred H. Napoleonic Army Organization, Circa 1812. Visalia, Jack Scruby, 1965.

More Roots of Wargaming

-

Robert Louis Stevenson

H.G. Wells

Shambattle

Children and Toy Soldiers

Links Between Military Miniature Collecting and Gaming

Jack Scruby

1962

Table Top Talk Magazine

Naval Wargames Part 1

Naval Wargames Part 2

Air Wargames

Horse and Musket I

Napoleon Rides Again

Featherstone Again

Wargaming Literati

Back to The Herald 47 Table of Contents

Back to The Herald List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by HMGS-GL.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com