The tramp of feet and the beating of hooves; the tramp of feet and the clank of tank tracks; the splashing of oars in the sea; the wind in the rigging; the chugging of the warshipsâ engines -- we've encountered all of these sounds in the gaming we've been introduced to in our exploration of the literature of our hobby. But there's still one sound we haven't listened to at length -- the buzzing of aircraft engines as they roar overhead on their battlefield missions. So, let your imagination take hold again as we enter the world of air wargaming.

We're back in the mid-1960s again, and our compiler is, no surprise here, Donald Featherstone. In the third book in his wargaming trilogy, Featherstone introduces a collection of ideas for using air forces in miniature gaming, from the introduction of balloons into the American Civil War to the modern era. "Air War Games" follows a format similar to the earlier volumes, presenting an overview of the hobby, including boardgames, descriptions of the models available, a review of the concepts of gaming and provision of resources for researching the historical and technical background.

Reviewing the list of model planes available, especially the Airfix list, was an exercise in nostalgia for me. Many of those models had hung from my ceiling...and later succumbed to a barrage of firecrackers. It was a bit of a surprise to see how long the lists turned out to be, with a fair group of World War I aircraft and a pretty comprehensive World War II selection. Of course, at 1:72 and 1:48 scale, it took quite a bit of room to maneuver these craft, and therein lies the main problem inherent in this aspect of wargaming.

Space. Three dimensions.

Space. Three dimensions.

The two factors that separate air war from ground, and to a lesser extent, naval war. One thing you notice right away when reading the ideas that Featherstone collects here, is the number of situations where aircraft are limited to ground support missions. Flying the planes on dive bombing/strafing/torpedo runs limits their participation to the periods and situations when they are immediately involved in the combat on the table. Especially for the later periods, the speeds of planes, even when scaled down, leave them little time over the battlefield, so the rules for using them can be relatively simple, often adaptations of off-board artillery rules, with provision for the attacked forces to use anti-aircraft fire. This broadens out somewhat for naval gaming, where the spatial relations are broader and air forces may take some time to move across the playing area.

The second element that pops up again and again is how to represent the planes on/over the table. Here we have the mechanical problem of how to physically place the model in space, as well as the derivative problems, which we've begun to see in naval games, of the more fluid and inertial factors in air, as opposed to ground, movement.

Let's look at the second problem first. Fletcher Pratt's naval rules included an aircraft component which used bases on the table with rods extending upwards for mounting aircraft cards or models. The rods had small platforms for the plane models to sit on, or which had silhouettes drawn on them. These platforms could be moved up and down on the rod to represent the vertical movement of the squadrons they represented. This provided a basic method for solving the three dimensional problem, and the use of rubber bands at various elevation points on the upright rod could also help keep track of fuel consumption. Another gamer used telescoping rods to provide for the vertical movement of the planes attached. Swivel joints attached to those rods made it possible to more accurately represent the greater variety of angles and positions. The problem with both of these methods it that there is a base on the table to contend with. If the battle is primarily an air one, this isn't much of a problem, but if there are ground troops or naval forces involved the bases, almost inevitably, end up interfering with the activity going on below the planes.

Solutions

There are two solutions proposed to avoid the problem of the traveling base. One is to provide an elevated "surface" for the planes to move on. This was often a web which the planes could sit on, though Plexiglas could be used, too. The latter was less convenient as the planes could be a considerable distance from the edge and awkward to move. But this was solved by attaching metal strips to the planes and using a magnet on the end of a stick to move them with. These ideas removed the bases from the table, but left the planes moving in a two dimensional space, just one that was somewhat higher than the action going on below. The concept reminded me of Khan's limited perspective in the second Star Trek movie. Still thinking in two dimensions, he forgot that space has three and allowed the Captain Kirk to slip below him to his own dismay. So, this only solves part of the problem of movement in air wargames.

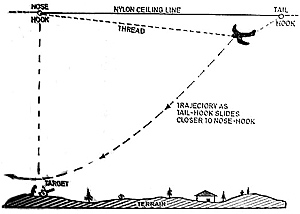

The third dimension is brought into play when the web used in the previous example provides a mounting system for planes suspended below it, rather than a base for them to ride upon. Mounting rings on the planes are attached to thin wires or strings of varying lengths to represent their vertical movement distances. Thus, as a plane dives into the attack, it uses longer and longer attachments to bring it closer to the "ground." Since there was often little need for sideways movement in the short space available over a battlefield, an alternative was to attach one long string from one side of the room to the other. The string would not be tight, so as the plane moved along its length it would gradually move closer to the tabletop and its target, then fly back upwards as the mission ended.

Certainly the overhead web, or variations on the hanging theme, seem the better solution for ground support actions where planes are swooping in and out relatively quickly. For plane to plane actions, it seems to me that all those wires and strings would be a problem to keep straight. And it seems that the contributors to this volume found that to be true, as most of their air to air games had some form of platform support for the aircraft involved. They also tended to look to room sized games, or took them outside, to provide enough space for even scaled down movement to reflect somewhat realistic maneuvering. With my penchant for miniaturization, I've restricted my own air war modeling to 1/300 scale planes. Even at this scale, World War I planes would be moving 30 feet per minute, more or less, so I've adapted some ideas borrowed from Charles Grant resulting in a 40-60" move. Still too big for plane to plane action, but adequate for ground support. For purely air combat I've adjusted the scale to a 20" average move, which still uses quite a bit of space, but keeps the highest flights within reach!

Some of the contributors didn't believe that plane to plane combat was even possible for any period after World War I, and with the speeds and maneuvering capabilities involved, they may be right. In any case, I haven't looked beyond that period in my own consideration of air to air wargaming. On the other hand, I have seen the Starship Enterprise, Millenium Falcon and other craft on the wargaming circuit, so there's apparently no restriction on the imaginations of wargamers at large! And, regardless of the limitation space may put on our ability to produce believable wargames for this type of fighting, aircraft perform many other missions that can be readily represented in combined arms operations.

ACW

As early as the Civil War, balloons began to provide reconnaissance. This function has certainly retained its importance, though the satellites used for similar data retrieval fly somewhat higher, and the people involved are quite a bit less exposed today! I've already mentioned ground support missions, whether bombing or strafing, and these became regular operations in World War I. Though not as dramatic as the dogfights, we imagine after watching Hell's Angels, these missions can add a new factor and flavor to an otherwise ground based game. In any game with hidden movement, or restricted information of any sort, observation balloons and planes take on an important role in discovering the opponent's dispersal. And providing ground support can put extra firepower into play at a decisive point or time that might otherwise be unavailable. Of course, anti-aircraft fire must also be provided for to match this new factor in the game, and some simplified plane-to-plane rules can be introduced to represent that possibility for the short time the craft are over the battlefield. In later periods, the missions for aircraft become more diverse as paratroop and glider missions may be introduced, and high level bombing and tank busting become more important. But, for the most part, the standard reconnaissance and ground support missions are the easiest to integrate into the game.

Much of the book takes the form of a collection of ideas used by various gamers for integrating aircraft into their land and sea gaming. Having Featherstone's earlier books in hand provides both a toolkit for mixing and matching ideas you like, as well as an overview of the "Featherstone system" of wargaming, circa 1966. We've encountered several of these wargamers before, with Fred Jane and Fletcher Pratt providing the two examples of published naval rules which included an aerial component. Jane's use of the "dart" approach is in play here, as he suggests using a cork with a pin it to represent bombs, to be dropped from a height of 1" for each 100 feet represented. I've described Pratt's use of a vertical rod to represent the height (and fuel consumption) of the planes involved in his naval game. His use of the aircraft followed the pattern of the naval vessels in the game with some simplification.

Much of the book takes the form of a collection of ideas used by various gamers for integrating aircraft into their land and sea gaming. Having Featherstone's earlier books in hand provides both a toolkit for mixing and matching ideas you like, as well as an overview of the "Featherstone system" of wargaming, circa 1966. We've encountered several of these wargamers before, with Fred Jane and Fletcher Pratt providing the two examples of published naval rules which included an aerial component. Jane's use of the "dart" approach is in play here, as he suggests using a cork with a pin it to represent bombs, to be dropped from a height of 1" for each 100 feet represented. I've described Pratt's use of a vertical rod to represent the height (and fuel consumption) of the planes involved in his naval game. His use of the aircraft followed the pattern of the naval vessels in the game with some simplification.

Featherstone

Featherstone builds on Pratt's ideas for constructing ship cards which provided a method for gradually reducing the fighting effectiveness of a vessel, by using a similar method to make plane cards. This permits a game very similar to Pratt's naval game, but in three dimensions. Firing arrows are used to aim and estimate ranges, then hits are noted and damage assessed on the individual plane cards. Keeping in mind that Pratt's rules call for timed movement and firing, this is a quick moving, exciting and frustrating game.

With the publication of "Air War Games," Featherstone had put between hard covers an overview of the three main areas of military concern -- land, sea and air. While War Games began with quite complete rules for land wargames, by the time we reach aerial combat we're on much looser ground with concepts being discussed more than full blown rules. It's quite instructive to see the ideas being shared among gamers of the time and to note how useful many of them may still be in our gaming.

The downside of all of this is that I've added another period to my collection! The Red Baron flies again. Where are you Snoopy?

Source:

Featherstone, Donald. Air War Games. New Rochelle: Sportshelf, 1966.

More Roots of Wargaming

-

Robert Louis Stevenson

H.G. Wells

Shambattle

Children and Toy Soldiers

Links Between Military Miniature Collecting and Gaming

Jack Scruby

1962

Table Top Talk Magazine

Naval Wargames Part 1

Naval Wargames Part 2

Air Wargames

Horse and Musket I

Napoleon Rides Again

Featherstone Again

Back to The Herald 45 Table of Contents

Back to The Herald List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by HMGS-GL.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com