No matter where you look in modem wargaming, you come across the name Featherstone. Naval wargaming is no exception. After publication of War Games, dealing with ground warfare, in 1962, Donald Featherstone found enough interest, and material to follow up with a second volume for naval war. As we've seen with the earlier book, this one combines Featherstone's own contributions to the hobby with those of many other gamers and rules' authors.

No matter where you look in modem wargaming, you come across the name Featherstone. Naval wargaming is no exception. After publication of War Games, dealing with ground warfare, in 1962, Donald Featherstone found enough interest, and material to follow up with a second volume for naval war. As we've seen with the earlier book, this one combines Featherstone's own contributions to the hobby with those of many other gamers and rules' authors.

Featherstone found that the literature for naval wargaming was much rarer than that for land war. Since the land wargaming library is spare enough, the naval shelf is nearly bare! His initial contact with the British War Office in preparation for the earlier book netted a list of 97 items. Starting work on this volume using the same method, his approach to the Admiralty Library turned up only Fred T. Jane's rules from the beginning of the century. As It turns out, we looked at the only major rules published prior to this book in the last installment.

'Naval War Games'

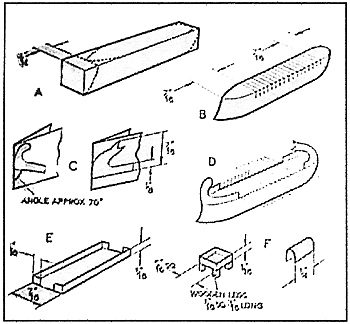

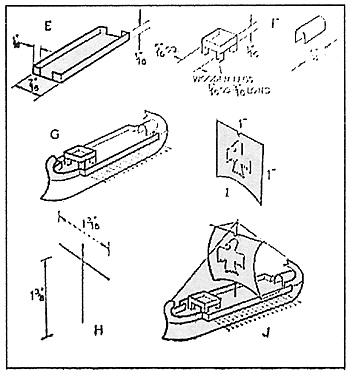

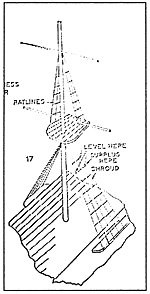

Naval War Games begins with a summary of the current state-of-the-art, including boardgames and models available in the mid-60s. Remember Battleships, U-Boat or Bismarck? There's an interesting section on constructing home made model ships which look pretty simple to do ... at least until you get to rigging the sailing vessels! But then the modem ships become simpler again. Joe Morschauser, who we've met before in this series, contributes a piece on "Table-Top Islands." Here he combines the land war games we're already familiar into an island hopping context with tables scattered about a room representing the land areas and broomstick mounted ships traveling between them to ferry troops, or battle one another.

Naval War Games' format echoes the earlier volume with the majority of the rules he discusses following a chronological sequence. However, the rules are much more distinct. Unlike the land based rules, in which the more recent periods' rules build upon the older, these are largely based on new formats for each period, reflecting their varying authorship, though there remains a Featherstonian flavor throughout many of the rules. The work of Pratt and Jane is also evident in many places. As with the land wars of War Games, Tony Bath contributes a basic set of ancient rules to the collection.

Once again, Featherstone's volume provides the basic rule set needed to play the game, except that, with boarding such an important part of ancient naval war, we need to have the earlier volume in hand to have a complete set of rules as Bath played them. For our gaming here in the hills of northwestern Pennsylvania, I've created a variant which uses a quick roll of the dice to determine the outcome of boarding actions. Since we tend to use boarding more than Bath intended, it's probably a good idea not to have to fight each action out, especially if there are more than a hand full of ships on the table!

(OK, I have to admit that the real reason for the variant is that I haven't gotten around to finishing the paint job on the figs I bought for the purpose. Nonetheless, playing by the rules would take a lot longer, the way we go at it!)

Tony Bath's Mechanics

This was the first naval miniatures game I played, and, unfamiliar as I am with naval war, it was apparent that the ebb and flow of a naval battle is substantially different than that on land. The game mechanics are simple, yet force players into patterns of movement that would occur in ancient naval actions. Whether paddling a canoe or trireme, or driving an oil tanker, movement on the water follows different patterns than on land. A naval game must reflect those differences and, with a few simple mechanical devices, Bath does a decent job of recreating those patterns, at least for this uneducated naval wargamer.

This was the first naval miniatures game I played, and, unfamiliar as I am with naval war, it was apparent that the ebb and flow of a naval battle is substantially different than that on land. The game mechanics are simple, yet force players into patterns of movement that would occur in ancient naval actions. Whether paddling a canoe or trireme, or driving an oil tanker, movement on the water follows different patterns than on land. A naval game must reflect those differences and, with a few simple mechanical devices, Bath does a decent job of recreating those patterns, at least for this uneducated naval wargamer.

The basic rule is that a ship must move forward before making a turn, and the amount of each turn is limited so that turns of ninety degrees are all that can occur in one player's move if there's forward motion. Ships may turn in place, or back paddle straight to the rear, but that is all they can do in a turn. Provision is made for movement under sail, as well as by oars.

Bath's view of ancient naval war was that ramming was the dominant tactic, and the rules are oriented to encourage it. He's also adapted his land war rules for boarding actions and missile fire. In our games, we've found that boarding still occurs relatively frequently. I'm not sure if it's just that we're unfamiliar with the concepts of naval war, and, like the Romans on the sea, are trying to turn it into land war, or if there's a problem with the rules (or our implementation of them) that we haven't identified.

Regardless, the rules provide for a quick and entertaining game-, our actions with 7 or 8 vessels on each side only lasting half an hour, or so...

Gunpowder

The advent of gunpowder changed the dynamics of sea warfare from a close combat battle to a ranged one, just as it did on land. While the movement mechanics must continue to reflect the inertial effects inherent on, and in, the water, the combat mechanics now increasingly adopt those of artillery on land, though provision for ramming and boarding must still be provided for. We are now bombarding moving targets which have increasingly thick armor.

We also move from muscle, to wind and then steam, diesel and nuclear power over the centuries. Each of these changes affects the specific mechanics of rules devoted to particular periods, but the main concerns are consistent -- speed, armament and armor. In earlier periods, for example, speed is determined by the amount of sail, related to wind speed and direction. As damage is accumulated the sails deteriorate and the speed and maneuverability of the ship decreases. Later, damage to hulls and propellers, and overall damage to a ship reflecting command and control problems, accumulate in the same way to slow vessels in the, fights they've encountered. Of course, damage to guns affects firepower and hits on hull armor ultimately sink vessels.

Naval War Games includes rules for 16th to 19th century sail based battles. The American Civil War provides a particularly interesting opportunity for steamboat actions on rivers, and also sees the introduction of submarine assault. It also serves as a transition point for the change to ironclad and steam powered vessels. The various rules come from a variety of gamers, culminating in fairly complete descriptions of the rules of Jane and Pratt that we reviewed last time. Indeed, it appears that those rules were still the most complete published sets up to, and including, this volume.

We played with Pratt's rules on a very small scale, with two battleships facing off, the slightly smaller one having a destroyer in support. Pratt's game, like Bath's, moves along quickly. Moves and preparation for fire are timed, the former taking 45 seconds and

the latter 60 seconds. If players were using more than a couple of vessels, these time limits would have to be extended, but under the normal setting, with each participant "Captaining" a single ship, the limits keep things moving along and force quick decisions. Movement is simple, with flexible measurement guides aiding in recreating the curving flow of naval movement. As our two battleships engaged, their paths wove in circles, as each tried to bring maximum firepower to bear, or to present the most difficult target.

We played with Pratt's rules on a very small scale, with two battleships facing off, the slightly smaller one having a destroyer in support. Pratt's game, like Bath's, moves along quickly. Moves and preparation for fire are timed, the former taking 45 seconds and

the latter 60 seconds. If players were using more than a couple of vessels, these time limits would have to be extended, but under the normal setting, with each participant "Captaining" a single ship, the limits keep things moving along and force quick decisions. Movement is simple, with flexible measurement guides aiding in recreating the curving flow of naval movement. As our two battleships engaged, their paths wove in circles, as each tried to bring maximum firepower to bear, or to present the most difficult target.

The real difficulty came in targeting, with the time limit a major complicating factor. Each caliber of weapon was targeted separately, with firing arrows providing the aiming direction. So the first skill came in aiming. Then ranges had to be estimated, in centimeters to complicate things for us, and noted on the arrows. Even within our small playing area, estimating and aiming proved challenging. Luckily for me, my estimation skills are superior to my dice throwing ones! One "lucky" salvo blew my destroyer out of the water, but by our time limit, his battleship was near to sinking, while mine had suffered only minor damage.

These rules are very playable, They move along rapidly. The time consuming part is in creating the point structure for each vessel, Of course, once done, they can be used again, so it's a one time task for each ship. We found that it was helpful to have a ship diagram to identify the hit locations in order to determine whether port or starboard, bow or stem weapons were destroyed. Even with revolving turrets, all the guns were limited in their fields of fire, so knowing which were available had a significant effect on firepower as the ships maneuvered around each other. This isn't in Pratt's original rules, and may be an unnecessary complication, but we found it added a bit of spice to the affair.

Interesting 'Grab Bag'

Featherstone finishes up the volume with a kind of grab bag of ideas for adding flavor to naval war gaming, some comments on which wars might present interesting gaming possibilities, thoughts on, and several examples of combined arms games with both land and sea forces involved, and ends with a fairly substantial list of reference sources for naval war history and practice, combined arms games with both land and sea forces involved, and ends with a fairly substantial list of reference sources for naval war history and practice. The grab bag has some interesting ideas combed, to a great extent, from the wargaming periodicals of the day.

The importance of morale is made evident by his example of the battle of Lissa where an Italian ironside was presented with the opportunity to fire a broadside at a very nearby Austrian vessel. Unfortunately, in the excitement of battle, the Italian crew forgot to load their guns! Methods of fire are discussed at some length. We've seen how Pratt's estimation technique could lead to a certain randomness of result, and, of course, we're all familiar with the delightful vagaries of rolling dice. What might not come to mind, is another variant on H. G. Wells' use of firing model cannons -- Tiddly Winks. You remember those, don't you? The Model General's Club of America came up with this one, introducing another type of skill factor into the firing process. Hits were defined as anything within 3 inches of the target, or into a cup for the more skilled tiddly-winkers.

Weather

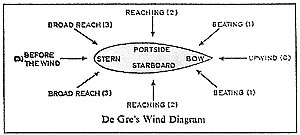

Of course, weather plays an important role in sea warfare. In the Age of Sail, wind is a critical factor, later, fog is of special concern, since the distances of modem war allow ships to appear and disappear in fog banks, or smoke screens, for that matter. The wind can have an effect on the sea itself, with firing becoming more difficult in heavier weather as ships rise and fall with the waves.

Of course, weather plays an important role in sea warfare. In the Age of Sail, wind is a critical factor, later, fog is of special concern, since the distances of modem war allow ships to appear and disappear in fog banks, or smoke screens, for that matter. The wind can have an effect on the sea itself, with firing becoming more difficult in heavier weather as ships rise and fall with the waves.

The weather issue can affect one's arena of choice, as well. The comment is made that the North Sea isn't a practical one for gainers, since fog is such a factor. It tends to make the games more a case of chance, as ships find each other in the fog, than one of skilled maneuver and fire. The Mediterranean's relatively clear and calm weather suggests that it is a more pleasant venue for naval affairs. And there appear to be plenty to revisit on the wargaming table, or floor, the earlier conflict with Italians and Austrians facing off coming quickly to mind. Just remember to load if you're playing the Italians!

Of course, most naval warfare has taken place in the context of a conflict with a major land based component. And much naval activity has been in direct and immediate support of the latter, ferrying troops, providing bombardments, and so on. What's presented here combine these ideas with ships used for both moving troops to seize objectives, and providing fire support in more modern periods.

Whether straight up naval fights, or part of a campaign with land forces, naval war games provide an interesting respite from purely land based situations. The flowing, inertial feel of movement is a feature I find intriguing as I examine this new-to-me arena. And, as Featherstone notes, one of the opportunities provided by naval gaming is that we can often use the actual number of ships used in the historical battle in our miniature one, something that, except for skirmish level conflicts, is rarely possible for land based games. Even though we're looking back 35 years, Featherstone's book provides us with enough tools to work with to add another useful and entertaining facet to our gaming universe.

Sources

Featherstone, Donald R Naval War Games. London: Stanley Paul, 1965.

Pratt, Fletcher. Fletcher Pratt's Naval War Game. Milwaukee: Z & M Publishing, 1976.

More Roots of Wargaming

-

Robert Louis Stevenson

H.G. Wells

Shambattle

Children and Toy Soldiers

Links Between Military Miniature Collecting and Gaming

Jack Scruby

1962

Table Top Talk Magazine

Naval Wargames Part 1

Naval Wargames Part 2

Air Wargames

Horse and Musket I

Napoleon Rides Again

Featherstone Again

Back to The Herald 44 Table of Contents

Back to The Herald List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by HMGS-GL.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com