Reviewing the list of wargaming publications for these early days could lead one to assume that the Napoleonic era was predominant. While we've seen that ancient and modern war were written about, the Horse and Musket period, with emphasis on the Napoleonic years, seems to have gotten more than its fair share of print. Some of the rules we've looked at were not so specific as to name a period, but from Wells and Shambattle forward, the emphasis was on cavalry, infantry and artillery (horse, musket and cannon).

Reviewing the list of wargaming publications for these early days could lead one to assume that the Napoleonic era was predominant. While we've seen that ancient and modern war were written about, the Horse and Musket period, with emphasis on the Napoleonic years, seems to have gotten more than its fair share of print. Some of the rules we've looked at were not so specific as to name a period, but from Wells and Shambattle forward, the emphasis was on cavalry, infantry and artillery (horse, musket and cannon).

The past year's articles in this series dealt largely with the literature of the mid-1960s, looking especially at Donald Featherstone's reviews of the state of the art. Necessarily, his volumes covered the gamut of wargaming periods. Other authors, in the later 60s, did much the same in their introductory wargaming texts. However, even as he was producing his overviews, the wargaming world was beginning to see publications devoted to specific periods as well. And, at this stage, Napoleonics dominated, with three titles coming out in quick succession.

We'll start our review on the west coast and work our way back east, which, coincidentally, will follow the temporal pattern as well. The earliest of these stand alone rule sets was Jack Scruby's Fire and Charge. His early periodicals included significant coverage of the horse and musket era and his catalog had a healthy representation of Napoleonic and other figures of the period. So it was no surprise that his other publications would also cover this "middle age" of warfare.

Those of you who've read my piece reprising Scruby's "Unbalanced Equality" rules for 19th century colonial war (Herald #26) will recognize many of the concepts in Fire and Charge. From All about Wargames (Herald #40) through The Strategy-Tactical Wargame (Herald #41) to Fire and Charge there was a continuity of concept in Scruby's gaming. One of those concepts is clearly noted right at the beginning of this volume. Making no claims to originality, he states that the ideas in these rules were borrowed from many other wargamers -- so our first idea is to borrow what we like best. In any case, it's easy to see the threads that he preferred.

It was here that I encountered the "Morschauser Roster System" for the first time. It was years, decades, rather, before I found out who Morschauser was (Herald #41), but I used his system regularly during those years. With figures mounted on stands, an army could represent hundreds or thousands of troops with relatively small numbers of miniatures in hand. This was an eye opener for someone who'd always used single figures. The format lent itself to other simplifications, too. For example, Scruby made musket volley hits automatic, assuming that such fire would do some damage in any case. In larger battles, this saved a lot of dice rolling. Artillery and carbine fire as well as musket fire against defensive positions still demanded a random factor.

Scruby's regiments were made up of six stands of infantry. Each stand represented a company with the first company in all line regiments the grenadiers. These were somewhat stronger than average troops, suffered fewer morale problems, and had a bit more staying power in battle. The second company was the light infantry (voltigeurs). These were a bit quicker and could be broken up into two stands to provide screening for the rest of the regiment. The balance of the infantry were the line troops (fusiliers), the vast majority of the figures on the table.

Scruby's regiments were made up of six stands of infantry. Each stand represented a company with the first company in all line regiments the grenadiers. These were somewhat stronger than average troops, suffered fewer morale problems, and had a bit more staying power in battle. The second company was the light infantry (voltigeurs). These were a bit quicker and could be broken up into two stands to provide screening for the rest of the regiment. The balance of the infantry were the line troops (fusiliers), the vast majority of the figures on the table.

Cavalry were divided into light and heavy, with the lights able to move more quickly and provide some firepower, as well as dismount to improve their firepower and seize positions. The heavy cavalry were fearsome indeed for infantry caught in the open, but had trouble against defensive positions and squares. In addition to the basic troop types there were elite guard infantry who were also broken into lights and grenadiers. Like line grenadiers, these troops were stronger in combat and morale than the regular fusiliers. They also had automatic firepower at all times, not having to roll a die against any positions.

Movement was done simultaneously by both sides, the winner of a die roll choosing which flank to begin moving from. After movement came combat, with artillery fire taking place first and those casualties taken immediately. The winner of the initial die roll got to take the first shots -- an advantage to winning the initiative. Following artillery fire, musket fire was calculated. This was simultaneous, so all hits were taken before stands were removed. Post-volley morale effects were then taken with the losers of firefights retiring to their rear. Finally, melees were fought and any morale effects and bonus moves resulting from these hand-to-hand fights were exercised. Then it was back to the dice to roll for initiative in the next Game Move. A very straight forward system.

Of course, there was a lot of room for maneuver within this system and Scruby describes a number of possibilities that, as usual, he'd cribbed from other gamer's ideas. Not surprisingly, Fire and Charge is an important rule. This allows for a volley to be immediately followed by a charge into melee. Shock Power gave cavalry a chance to produce some casualties by the force of their impact, before the hand-to-hand combat of the melee was fought out.

There's a headquarters rule which simply provided for each side having two headquarters which were to be placed on the two halves of the table. Since losing a headquarters could lead to a loss of the game, this rule provided a somewhat artificial method of spreading troops across the battlefield.

The rules also were adaptable to the use of individual figures. This version allowed regimental scale battles to be fought with larger figures on the table than were used for the stand based games. Rather than using hits per stand, firepower was based on a percentage system. Thus, a base "killing factor" of 40% was set. However die rolls were used to modify this with a 50% chance of decreasing the effect of a volley. Other than that, and increasing the movement and range distances to accommodate the larger scale, the Individual War Game was identical to the stand based Unit War Game.

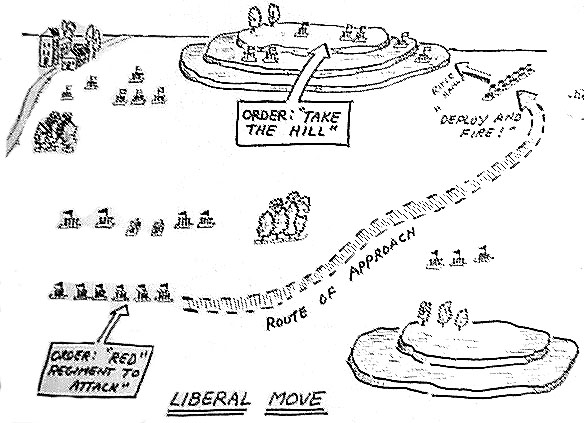

Liberal Move

But the rule that has stayed in my mind over the years, and which Scruby spends quite a bit of space describing, was the Liberal Move. Adapted from an idea originated by gamers in Greensboro, NC, the Liberal Move added a whole new dimension to the gaming table. Or maybe it just twisted one dimension -- Time. Essentially, this move allowed a player to work through as many moves as it took for one specific group of troops to accomplish, or fail to accomplish, a precisely defined task on the battlefield. While this was going on, all other activity on the table would cease. A Liberal Move might be used to simply move a group of troops by "forced march" to a critical point on the table, or it might serve to launch an assault on an important objective.

But the rule that has stayed in my mind over the years, and which Scruby spends quite a bit of space describing, was the Liberal Move. Adapted from an idea originated by gamers in Greensboro, NC, the Liberal Move added a whole new dimension to the gaming table. Or maybe it just twisted one dimension -- Time. Essentially, this move allowed a player to work through as many moves as it took for one specific group of troops to accomplish, or fail to accomplish, a precisely defined task on the battlefield. While this was going on, all other activity on the table would cease. A Liberal Move might be used to simply move a group of troops by "forced march" to a critical point on the table, or it might serve to launch an assault on an important objective.

The process was simple enough, but the whole dynamic of the game could change as a result. As Scruby states, "Realistic or not, it is the greatest rule we have run across in a long time, and makes the game twice as exciting and dangerous than any other idea I've heard about." (23) Having won the Game Move, a player would announce a Liberal Move. Another die roll gave a 67% chance that the move would actually occur. If it did, it had to be described very clearly, since once begun there was no backing out. Movement of the appropriate troops, and they would be limited to about 16% of the total effective force, was made one regulation movement at a time. During the movement, any enemy troops able to could fire on the moving force, which, if in a formation permitting it, could return fire. When the objective is reached the move is over, if it is undefended. If there are defenders, they may stand and fight, or perform a fighting withdrawal, but not counterattack.

During this combat, movement is in a move-countermove sequence, unlike the normal simultaneous movement, with the Liberal Move player moving first in each segment. I suspect that you can see how two edged a weapon this could be, with an attacking force finding itself too weak to perform its task when the objective is finally reached, or a defender suddenly finding a significant enemy force in a critical position. Hmm, did you remember to defend your headquarters?

Just to add a bit more flavor to the concept, Scruby introduces the Hit and Run Liberal Move. The main differences here are that only light troops may be used, and the move may be canceled at any time. When the move is canceled, the troops involved may be moved back to any point traveled along the route taken earlier. Hence, hit and run. These Liberal Moves were considered to have used up five normal movement turns, a significant portion of the normal 20 moves of a game. It's no surprise, then that night movement, which was a three turns in one situation, was provided for, with battles taken up in the morning after those moves were completed. The moves were carried out as during a normal turn, except that the distances were trebled. Oh, by the way, there was provision for a Night Liberal Move, too! Those troops were allowed to move six times the normal movement rate. Any combat resulting from this night movement was handled during the first move of the next day, after which the second turn of the day began.

With Fire and Charge, Scruby developed his basic rules into a format suitable for Napoleonic era wargaming. A bit of tweaking of ranges and troops capabilities provided a simple set of rules that could perform adequately for the whole Horse and Musket period. Next time, we'll look at Napoleonic rules that may be more realistic than Fire and Charge, but I think I'll miss that scary Liberal Move. Reference: Scruby, Jack. Fire and Charge. N.p.: N.p., 1964.

More Roots of Wargaming

-

Robert Louis Stevenson

H.G. Wells

Shambattle

Children and Toy Soldiers

Links Between Military Miniature Collecting and Gaming

Jack Scruby

1962

Table Top Talk Magazine

Naval Wargames Part 1

Naval Wargames Part 2

Air Wargames

Horse and Musket I

Napoleon Rides Again

Featherstone Again

Wargaming Literati

Back to The Herald 46 Table of Contents

Back to The Herald List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by HMGS-GL.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com